Brother Nhất Ấn shares how his life in Plum Village practice centers and following monastic practice can clarify the path to healing, both personally and globally.

At twenty-one years old I came into the monastery, leaving behind a life marked by anxiety and depression. I had dropped out of college because I was drowning. Waves of pain, sorrow, and hopelessness kept pulling me under, and I couldn’t find my way out. The weight of climate change,

Brother Nhất Ấn shares how his life in Plum Village practice centers and following monastic practice can clarify the path to healing, both personally and globally.

At twenty-one years old I came into the monastery, leaving behind a life marked by anxiety and depression. I had dropped out of college because I was drowning. Waves of pain, sorrow, and hopelessness kept pulling me under, and I couldn’t find my way out. The weight of climate change, ethical concerns about career choices, economic uncertainty, conflict and violence, widespread environmental destruction, and the plethora of suffering in the world was constantly overwhelming me, and I didn’t know how to deal with it all.

Questions about how to engage with the world without running away were always on my mind. Could I help without feeling trapped by the suffering around me? I felt powerless. The sky felt perpetually gray and the grass was no longer green. The beauty of the world had faded. I had lost my longing for life.

Lost in a cycle of overthinking and worrying about the future, I had forgotten my body. It became weak, thin, and fragile. Some days, I seldom ate and lost the physical and mental strength to get out of bed. I had lost all faith in society. It felt like the world didn’t care. The desire to blame someone was strong. I believed that if people just opened their eyes, we could solve these problems quite easily. I was naïve.

It wasn’t until I hit rock bottom that I realized I needed help. I was afraid of my own mind. I knew a part of me still wanted to live, but I didn’t know how. I wanted to help others, but every effort felt pointless. The challenges were too big, and I felt too small. Out of despair, I had admitted myself to a psychiatric hospital at nineteen years old.

That’s when I learned something that changed everything. I had to take care of myself first. I had let fear and despair take over my life. My psychiatrist gave me a simple yet profound suggestion: walk, pay attention to my breath, and reconnect with my body. He said, “You don’t know how to be happy. A dog can see anyone, eat anything, and be joyful. You are not a dog.” That became my mantra in a way. How could I go out into the world, no matter what was happening, and find joy and happiness? That was my task.

I began to understand that if I wanted to help end suffering in the world, I first needed to find peace within myself. How could I fight greed, ignorance, and intolerance in society if I couldn’t subdue them in my own mind? The battles inside and outside are connected. If I wanted real change, I had to confront my suffering, my feelings that I had stuffed down since I was a little boy. The emotions that I never learned to tame, to befriend, to listen to. If I didn’t learn to do this, my efforts would crumble under the weight of power, fame, sex, and greed, just as it happened to so many others.

Slowly I learned to be again. Lightness found its way back into my steps and with it came a firm determination to help others. But above all else, I learned to help myself, to prioritize my well-being. I knew my situation wasn’t unique and I knew I couldn’t navigate this path alone. It was necessary to find a community of people who understood this suffering, who had felt it and were committed to finding peace. That’s how the monastic path and Deer Park Monastery came into my life.

Just discovering the existence of the monastic path brought hope and light to guide me forward. The walls of my despair and anxiety began to crumble. The unendurable pain and mental anguish I felt softened up until their grip was gone. There were times when it seemed like these feelings would last forever, that my depression could never get better. But in time I learned about the nature of impermanence. Our happiness and joy, as well as our sorrow and despair, are not eternal. I was taught that if we want to be happy, we have to cultivate happiness every day, in every moment of our lives. The monastic path, it seemed, was a life dedicated to that practice.

After the pandemic travel restrictions were lifted, I spent a ninety-day retreat at Deer Park. It was a profound opportunity for self-discovery. I began to see clearly my shortcomings, my strengths, my areas of focus, and some blind spots I had overlooked for so long. Being in a community of like-minded spiritual practitioners was something I had never experienced before. The intensity of the monastery setting created the conditions for me to start unraveling the knots that had bound my mind for years. I was eager to continue this practice, so I pursued novice ordination.

The monastic path has served not only as my source of inspiration but also the means to produce meaningful action in response to the suffering in the world. I have felt that the spiritual path of Buddhism, and within it the practice of monasticism, is the direct antidote to the poisons of ignorance, greed, and hatred that fuel the struggles of humanity and society.

I began to discover that the world’s problems stem from our inability to face our internal suffering. We pass our pain to others through our actions, thoughts, and words. I had seen this firsthand in my relationship with my father. As a teenager, I resented his anger and swore I would never be like him. But through the practice of looking deeply, I realized that I am my father. His anger lived within me. It was passed down from many generations before, from our ancestors. I was blind to his suffering and the hurts that weren’t really his but were passed down from generation to generation, just as so many other traits were. There is still a hurt child in him that I had to acknowledge and befriend. One evening during sitting meditation, an image of my father and me as children appeared in my mind. I reached out my arms and gave him a hug as tears rolled down my face. I am forever grateful to my father now and for everything he has given me. I inherited his smile, his hardworking spirit, his playfulness, and his love for others. I vow to transform our unwholesome qualities not only for myself but for us.

If there is generational trauma, there must also be generational healing. When I heal, my family heals—my direct family, my ancestors, and my spiritual relatives. This is the nature of interbeing. We are interconnected, not separate from anyone or anything, even if at times we feel at odds.

We inter-are not just with our own families, but with all phenomena. The suffering of starving children, war-torn nations, drought-stricken farmlands, and bulldozed rainforests is all part of us. So are the cool breeze, the gentle rain, and the white clouds. Without them, we might not live, because they each play a part in our daily life. Politicians, military generals, and CEOs are human beings, their lives shaped by causes and conditions, just like us. If the seeds of suffering are watered within us, we too can become like them. Though the effects of their suffering may be magnified by their roles in society, at its core it is the same suffering we all endure: loneliness, anxiety, fear, and despair, which give rise to craving, hatred, ignorance, greed, violence, arrogance, and fanaticism.

Too often, we don’t know how to care for our own suffering. We are prone to react. We want to prove our strength, so we don’t become victims. But our real strength comes when we stop, pay attention to what’s happening inside, and transform our pain instead of passing it on. If we don’t, we become the oppressor, even if we feel like the victim. And of course, we need support. We need communities where we can come together to share our problems and our suffering, and to receive and share support, guidance, and space.

When I found The Five Mindfulness Trainings given to us by Thầy, they gave me clear, concrete guidelines while still acknowledging the suffering that existed in myself and in the world. I began to feel that this was a path I could follow, as The Five Mindfulness Trainings were not rigid rules but guiding principles. They acted like a compass, pointing me in the right direction. The Second Training, True Happiness, in particular struck me because it dealt with the exact circumstances that brought me to the practice. It is a reminder for me that happiness is the path itself, not the destination. That the suffering in the world can only be soothed, embraced, and transformed step by step, breath by breath. Living as a spiritual practitioner and a monk has shown me that the suffering in the world and the suffering we carry within us personally are not separate from each other.

The Second of The Five Mindfulness Trainings: True Happiness

Aware of the suffering caused by exploitation, social injustice, stealing, and oppression, I am committed to practicing generosity in my thinking, speaking, and acting. I am determined not to steal and not to possess anything that should belong to others; and I will share my time, energy, and material resources with those who are in need. I will practice looking deeply to see that the happiness and suffering of others are not separate from my own happiness and suffering; that true happiness is not possible without understanding and compassion; and that running after wealth, fame, power and sensual pleasures can bring much suffering and despair. I am aware that happiness depends on my mental attitude and not on external conditions, and that I can live happily in the present moment simply by remembering that I already have more than enough conditions to be happy. I am committed to practicing Right Livelihood so that I can help reduce the suffering of living beings on Earth and stop contributing to climate change.

In Buddhism, there is a teaching called the Six Pāramitās, or Six Perfections. If we wish to journey from the land of sorrow and despair to the land of joy and happiness, we must put forth effort every day to get there. We can’t just go online, buy a plane ticket, and arrive there. This effort is the practice of these Pāramitās. I want to focus on the third Pāramitā, which has been of great importance in my life, called Kshanti Pāramitā, which can mean inclusiveness, the ability to receive, accept, embrace, and transform the pain inflicted upon us.

Each of us has a certain capacity to endure injustice, but if we are forced to bear more than we can handle, we may break. Whether we suffer depends on our capacity to understand and accept. Some people can hear the same harsh words or face the same mistreatment we do, yet remain unaffected. Their hearts are vast like an ocean, capable of receiving and embracing without anger or frustration. This is why the practice of expanding our ability to embrace and include is so important. Through practice and training, the capacity of our heart will grow, and we can suffer much less. There are still moments in the monastery when suffering arises. Even as I write this article, I notice the seeds of depression and despair within me coming up, echoes of a struggle I continue to navigate. I am still learning to fully understand and accept myself, to make peace with my past, and to approach my mind without fear. I am aware that certain triggers can still stir up deep sadness, but part of my practice is learning to accept my mind exactly as it is, without judgment. I’ve come to realize that trying to repress or push away my suffering only intensifies it. Now, I understand that healing begins with embracing my pain, not avoiding it.

Kshanti can be easily misunderstood or mispracticed as running away from the world, becoming numb or complacent. Although it wasn’t intentional on my part, I adopted those unwholesome habits in the past to avoid being constantly overwhelmed. To develop this capacity, we must be able to look directly at the world, see it for what it is, and understand its true nature. If we have this capacity, we can smile and remain at peace instead of reacting when we are faced with adversity. We call someone with these qualities a bodhisattva or an awakened person. They are not driven by their own benefit or gain, but live with a deep commitment to help relieve the suffering in themselves and in the world by bringing harmony and improving the well-being of others.

Although these teachings are called perfections, we should remember that human beings are inherently imperfect, and the trap of unhealthy and unnecessary self-criticism is easy to fall into. I’ve experienced this firsthand, as many in the world are often raised with the expectation to excel constantly, both from family and societal pressures. I grew up feeling like I always had to be at the top; failure or ineptitude simply wasn’t an option. But this relentless pursuit of perfection can lead to burnout, causing us to inevitably tumble from the tower of hubris we’ve constructed over a lifetime. My previous notions of success were just ideas fed to me, but I didn’t really want them for myself. I was just constantly trying to prove that I was enough. I didn’t feel I was worthy of love, kindness, rest, or relaxation. I didn’t know how to give myself that approval. If we don’t have the ability to cultivate self-compassion, we easily risk succumbing to feelings of inadequacy.

Just as with the practice of cultivating happiness, compassion is not a destination; it is the path itself. With every action of body, speech, and mind, we must learn to love, understand, and care for ourselves. As we do, this energy will naturally grow within us. Only when we have nurtured compassion for ourselves can we truly extend it to others. For much of my life, I didn’t know how to be compassionate toward myself, and no one had taught me its importance. But now, I’ve learned to be that teacher for myself, to be the adult I once needed, the guide I had been searching for. Once I was able to generate compassion within, finding a way forward became much clearer.

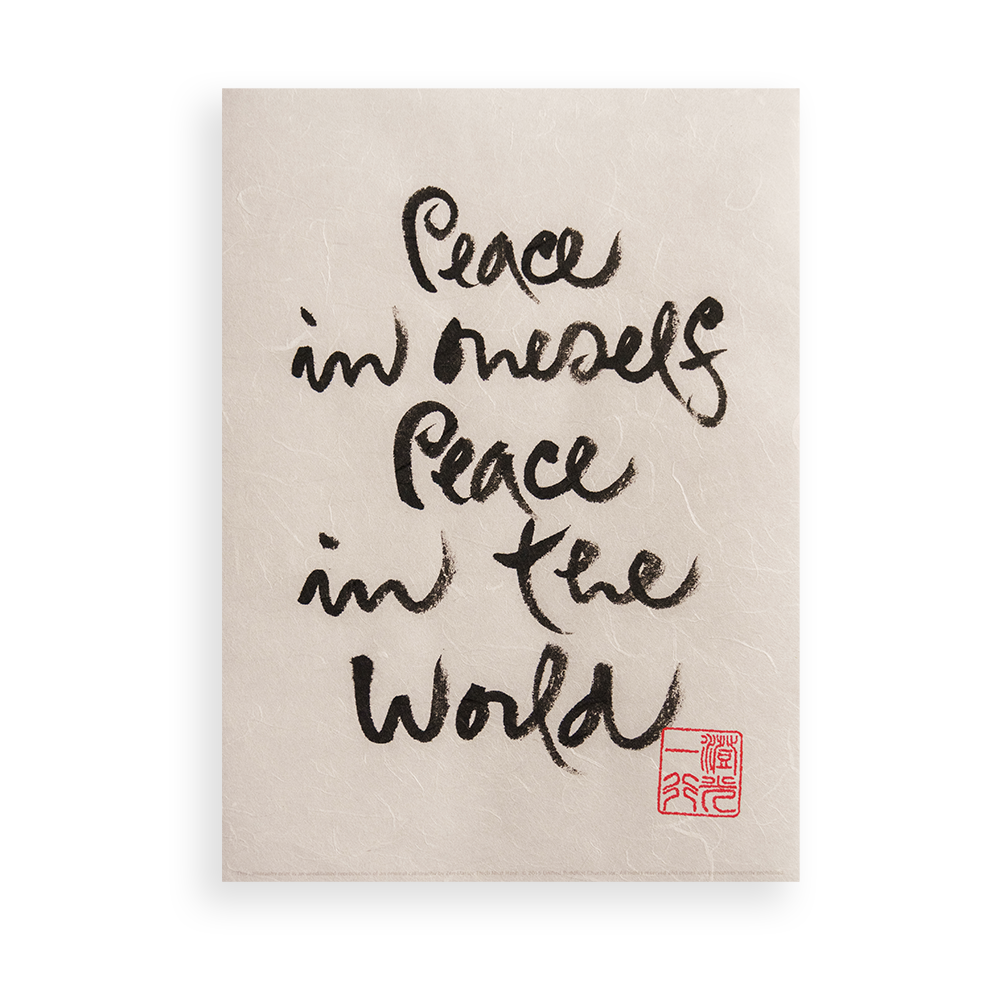

Now, as I celebrate my second year as a monk, I see that the questions that weighed on me—such as how to engage with the world’s suffering, and how to find meaning in the face of overwhelming despair—are the same questions I still hold today. But there is a stark difference now. Whereas before I felt powerless, overwhelmed by the enormity of the world’s pain, I now understand that meaningful change begins inward. Monastic life has shown me that the path to healing, both personally and globally, is not about grand gestures or solving everything at once, it’s about cultivating peace in each moment of our daily lives, in each breath and each step. The problems I once feared haven’t disappeared, but I’m beginning to understand that true happiness doesn’t depend on external conditions. Ultimately, the monastic path is not a retreat from the world but a powerful call to engage with it more deeply. It reminds us that through inner work, we inspire meaningful change in our communities and beyond. As one of Thầy’s famous calligraphies reads: “Peace in oneself, peace in the world.” By tending to our own suffering, we begin to heal the suffering around us. And as we heal, we become more capable of helping others do the same.

Slowly, I see myself becoming like a well-rooted tree, unshaken by heavy rain or strong winds. Though I may sway under pressure, storms will pass and the sun always rises. The work is never finished, but the path is clear. With every breath and in every step, I remember that healing the world starts with healing myself.

photos at Escondido Rock, Deer Park Monastery courtesy of the Deer Park monastic sangha