By Brandon Rennels

The first time I stepped into a monastery was the fall of 2011 at Deer Park in California. I arrived on a sunny September afternoon, and vividly remember scanning the retreat schedule on the bulletin board and seeing many practices I was familiar with: sitting meditation, walking meditation, and eating meditation. But when I saw working meditation, I paused. “How does one practice meditation when working?” I wondered.

By Brandon Rennels

The first time I stepped into a monastery was the fall of 2011 at Deer Park in California. I arrived on a sunny September afternoon, and vividly remember scanning the retreat schedule on the bulletin board and seeing many practices I was familiar with: sitting meditation, walking meditation, and eating meditation. But when I saw working meditation, I paused. “How does one practice meditation when working?” I wondered.

At the time I was taking a sabbatical from a career as a management consultant, and up to that point I often put my work above everything else. My mindfulness practice functioned as a kind of sanctuary, a refuge I went to when I wanted to stop working. A large part of why I came on retreat was to get away from all the work I had been doing, and now these people were going to put me back to work? I tried to keep an open mind, but was not enthused at the idea.

As the retreat progressed, however, something began to shift. My Dharma sharing group was a business affinity group, and as we shared our experiences and reflected on Thay’s teachings, it became clear to me that work was one of the most fertile grounds to explore mindfulness. Most of us spend countless hours working in one form or another throughout our lives, much more so than we spend in sitting meditation, walking, or eating. And if the sheer volume of hours wasn’t enough, the concept of work for most people—myself included—carries all kinds of associations, mental formations, habit patterns, hopes, and fears.

As I looked around at the monks and nuns that week, I imagined how much work had gone into setting up a retreat like this one. It was easy for me to sing “Happiness Is Here and Now” before a peaceful walk in nature, but I was curious what it was like for them to house, feed, teach, and care for over a thousand people. What were the logistics involved in that?

At the end of the week, I asked my Dharma sharing facilitator if I could be of service in helping the community. My request found its way to the right person, and next thing I knew I was in Plum Village for the winter. I became heavily involved with the Wake Up movement, helping to grow young adult mindfulness communities around the world. I began to work alongside many other practitioners, lay and monastic, locally and globally, and found it both enjoyable and challenging.

One of the most important lessons I received about mindfulness at work came from Brother Phap Dung that winter. We had been working on a few projects together, and one day I shared with him my frustration over a particular project that wasn’t on schedule. I blamed others for doing a poor job and for not being on time with their work. Brother Phap Dung nodded and listened patiently. Then he shared something that has stuck with me ever since: “Brandon, when we’re working on a project, there are always two goals. The first goal is to accomplish the project. The second is to be aware of our relationship to the project, to see our habit energies at play, and to nurture our compassion. This second goal is always more important."

I was stunned. This was a Dharma bomb of insight, and I felt its reverberations. Brother Phap Dung encouraged me to look deeper, to see my habit energies around wanting things to be perfect, and to see when and how I cut off my compassion for others. Maybe the person I worked with had something urgent come up, or they were confused on how to proceed, or maybe they were simply overwhelmed.

What I soon realized was that my ability to extend compassion to others when things didn’t go as planned was directly related to my capacity to extend compassion to myself. I noticed what kind of tone I used with myself when I didn’t live up to my own high bar: sometimes there was the disapproving internal voice of “You’re weak” along with a feeling of insurmountable lethargy. Other times my mind forecast a dark scenario: “You’re going to let them down and then they won’t want you around anymore. You could be kicked out of the monastery. Imagine trying to explain that to your parents after you left your high-paid job as a consultant.” With these internal messages came a corresponding rush of anxiety. In the past I would have used the anxiety as fuel to spurn myself to work harder, but nothing about Thay’s teachings seemed to indicate that working harder was the appropriate response.

So what to do? A lot of stopping. A lot of breathing. A lot of bearing witness to the activity of mind. A lot of placing my hand on my heart and assuring myself that no matter what happened, I was committed to not withholding love from myself.

As I began to take care of my own relationship towards work, I shared more with others, opened up, and was honest about my own hopes and fears. First, I did this among trusted friends not involved in any way with my work, and then eventually with those I was working with. I found this level of communication, where members of a team shared honestly about their capacity and their struggles, allowed a lot of trust to be built and sometimes actually expedited the process of getting the job done.

After that winter I spent the next few years living, practicing, and working within the Plum Village community, and continued to explore what it meant to apply mindfulness towards work. One of my main takeaways from this period of my life was this: When I am taking good care of myself I have more energy and enthusiasm, more space for other people, and above all, more clarity on what is truly important.

There are truly limitless ways to practice mindfulness at work. A dear friend sometimes refers to mindfulness as “choose your own adventure.” In my experience, especially while working, I’ve found it to be true.

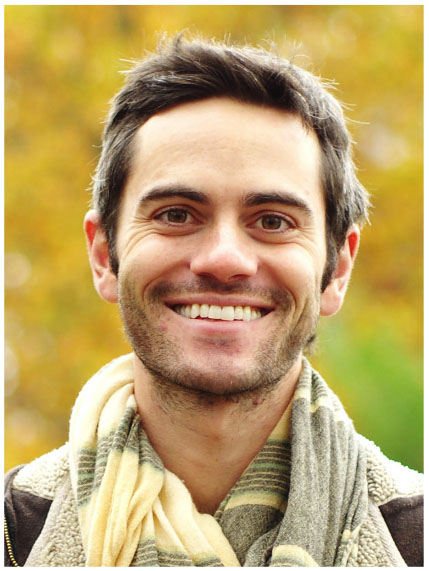

Brandon Rennels, True Garden of Faith, is a

management consultant by trade, who worked

for large corporations in Dubai before spending

a few years in residence at monasteries of Thich

Nhat Hanh. Currently, Brandon is the teacher

development manager at the Search Inside

Yourself Leadership Institute (SIYLI), a non-profit born at Google and based in San Francisco,

which offers mindfulness and leadership trainings

around the world.

THREE TIPS ON CULTIVATING MINDFUL WORK

1. Mindful Computer Breaks: I spend many days in front of a computer and find this to be an ongoing challenge to my practice of awareness. The first foundation of mindfulness is mindfulness of the body, but this awareness is easily lost when I am engaged in computer work. So I find it essential to build in regular non-negotiable breaks—at least every 60-90 minutes—where I get up, stretch, and recharge.

2. Watching and Debunking My Stories: A substantial portion of my work entails communicating with other people, and sometimes that communication doesn’t go the way I want it to: another opportunity to practice! I find it helpful to watch the stories that I tell myself about other people; often if there’s a conflict, I’m caught in a story that “they don’t care about me” or “they’re purposefully doing this to frustrate me.” But if someone doesn’t respond to my email, what’s more likely: they don’t care what I have to say, or their inbox is overflowing? In moments like this it’s helpful to think of the times I have been overwhelmed or struggling, and this generates compassion and a desire to support.

3. Purifying the Planning Mind: I spend a lot of time planning a project, whether it’d be a project, a teaching engagement, or just what I’m going to eat for dinner. Having learned long ago that trying to keep track of everything in my head is a bad idea, after a lot of experimentation, I use David Allen's “Getting Things Done” framework as a form of applied mindfulness.

But even with a solid framework, sometimes planning is accompanied by a sense of unsettled uncertainty; at these times I find it helpful to follow the tension to see what might be underneath. Often I notice tension is driven by my desire to control everything. Other times tension is complicated by a fear that if something happens, then I won’t be able to handle it—a fear of my own future non-resilience. Whenever I see clearly that fear is arising, it’s helpful for me to meet it with self-compassion: noticing where the fear manifests in my body, seeing if there are particular thought patterns arising, allowing both sensations and thoughts to be there without asking them to go away, and then offering myself love.