Reflections on Engaged Practice in the Holy Land

By Mitchell Ratner in November 2003

We did walking meditation together, each of us silently breathing and stepping, opening ourselves to the moment. We formed a circle and chanted together, giving homage to Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva who hears and responds to the suffering of the world. All of us had walked and chanted before,

Reflections on Engaged Practice in the Holy Land

By Mitchell Ratner in November 2003

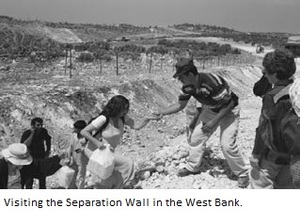

We did walking meditation together, each of us silently breathing and stepping, opening ourselves to the moment. We formed a circle and chanted together, giving homage to Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva who hears and responds to the suffering of the world. All of us had walked and chanted before, but this time the atmosphere was noticeably different—our walking trail was the approach to the Israeli military checkpoint that separates the Palestinian authority-controlled city of Nablus from the rest of the West Bank.

This checkpoint is often in the news. Many West Bank Palestinians need to cross it each day, to work, study, do business, or seek medical treatment. Journalists and foreign observers have substantiated Palestinian claims of needlessly long waits and degrading treatment by the guards. We had come to the checkpoint to offer a healing presence.

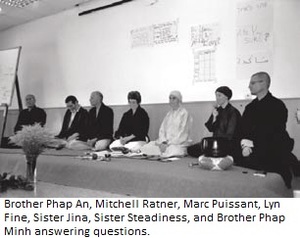

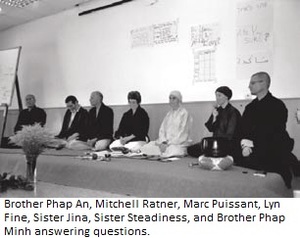

There were about twenty of us at the checkpoint that day in June of 2003. Eleven of us had come from outside Israel, including four Plum Village monastics, three lay Dharma teachers, and several Order of Interbeing members. We had come to Israel to share the practice of mindfulness and to open ourselves to the suffering, resilience, and wisdom that is present in Israel and the West Bank.

The international program began with a five-day mindfulness retreat at Givat Haviva, a kibbutz education center in the rural heartland of Israel. The international community joined with 50 Israelis to develop our practice of mindfulness. During the Dharma talks we talked about the Buddhist understanding of suffering and the overcoming of suffering. In Dharma discussion groups and private sharings, we talked about the particular suffering that Israelis felt, especially the daily fear that some unforeseen incident will bring great harm to them or their families, and the larger, overhanging sense of despair, that the situation will not improve.

Three themes emerged for me during the Givat Haviva retreat that helped me frame what I saw, heard, and experienced in Israel.

The first theme was about blame. With mindfulness we can develop the capacity to relate to ourselves and others without blame. As Thay Phap An noted in one of the Dharma talks, “Looking deeply is to be truly present, without blame or judgment.” In the context of Israel, the words resounded. Almost every public or private discussion of the Jewish-Arab conflict focuses on attributing blame. Each side justifies the suffering they have caused in terms of the suffering they have received. The suffering is not abstract or distant; almost everyone in Israel and the West Bank has a relative, friend, or acquaintance who has been killed or wounded.

The second theme was about the importance of our daily practice, of working with our own suffering. Sister Gina shared with the community how important it was for her to be able to take care of her own anger, fear, and defensiveness:

“I really have to practice. Only if I can do it, can I expect others to do it. If I cannot do it my daily life, there’s no hope. . . I would sink into despair for myself and for the world.”

This focus on the connection between our inner lives and the conditions we wish to see in the world is a special gift that mindfulness practice offers the peace movement.

The final, third theme was about the power of history, our own history and that of our community. At Givat Haviva most of the participants were Jewish and many of the discussions led back to the Holocaust. The question was often raised in terms of whether Israeli Jews, as individuals and as a community, had worked through the Holocaust—whether that unimaginably searing and painful experience had been fully processed so that it no longer clouded understanding of the current reality.

After Givat Haviva, the international participants, along with some of our Israeli hosts, spent a long day in the West Bank. In the morning we visited activists from a Palestinian village that will be cut off from its agricultural land by the new Israeli “security wall.” In the afternoon the residents of a small Palestinian community, near Nablus, offered us mint tea and told us about the struggles of their daily life, including attacks and harassment from an Israeli-Jewish settler community that has established outposts on the hills over their village, the general economic and social instability arising from the Israeli control of the West Bank, and the daily difficulties caused by the many blocked roads and Israeli checkpoints—what was a fifteen minute drive to Nablus had become at least a two-hour ordeal, and some days it was not possible to go there at all.

Following our stop at the Nablus checkpoint, we returned to Israel, and arrived late at night at Neve Shalom/Wahat alSalam (Oasis of Peace), an intentional community founded in the 1970s by a Dominican priest in the foothills between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. For more than twenty-five years Israeli Jews have lived as neighbors with Palestinian Arabs and Christians. Together they have created an international peace center, a bilingual/bi-national elementary school, and a retreat program that brings together Israeli Arab and Israeli Jewish high school students. A bumper sticker they make and distribute reads simply, in Hebrew and Arabic, “Peace Is Possible.”

Our next stop was Jerusalem, where we stayed for several nights with host families and together visited historical and spiritual sites, such as the Church of the Sepulcher (built on the site of Jesus’s crucifixion) and the Western or Wailing Wall (the last remnant of the second temple). One morning we visited the Holocaust Museum, Yad Vashem—a harrowingly effective presentation of what it meant, life by life, for six million people, one and a half million of them children, to have died, only because they were Jewish. Afterwards, we did walking meditation together in the hall of memory, holding each other’s hands, calming ourselves, struggling to simply breathe and remain open: not to close to the suffering, not to be overwhelmed by it.

An hour later we had lunch at the Jerusalem office of Action Reconciliation Service for Peace, a remarkable German non-governmental organization started in the 1950s by Protestant theologians. The organization’s founding principle was that when a great harm has been committed, there must be atonement before there can be reconciliation.

We Germans began World War II and for this reason alone, more than others, we are guilty for bringing immeasurable suffering to humankind. Germans have murdered millions of Jews in an outrageous rebellion against God. Those of us who did not want this annihilation did not do enough to prevent it. For this reason, we are still not at peace. There has not been true reconciliation. ...

We are requesting all peoples who suffered violence at our hands to allow us to perform good deeds in their countries, ... to carry out this symbol of reconciliation.

As Sabine Lohmann, the Jerusalem office’s director explained, more than thirty-five years after that statement, young Germans still come each year to Israel, and to similar offices in eleven other countries. In Israel they learn Hebrew, provide personal care to Holocaust survivors, and work in special education classes and with people with disabilities—classes of people especially affected by Nazi policy.

The still vivid images from the Holocaust museum, coming together with the German organizations efforts to reach to the roots of reconciliation, encouraged us, right there in the organization’s meeting room, to have an intense and cathartic sharing about World War II, Jews, Germans, cruelty, guilt, blame, and atonement. Thay Phap Minh, a Plum Village monk, born and raised in Israel, reminded us that demonizing almost always accompanies blaming. We separate ourselves by highlighting certain characteristics and ignoring others. For him, it was important to remember that “the dark side of the Nazi is within me and there’s great love in the heart of a Nazi.”

After several more events in Jerusalem, we headed north to Nazareth. While the retreat at Givat Haviva followed closely the structure of a standard mindfulness retreat, the events in Nazareth also included exchanges between the Israeli mindfulness community and other groups working for peace and reconciliation between Jews and Arabs.

During the days preceding the public events in Nazareth, the international group and Israeli organizers met with two extraordinary Arab groups. Memory for Peace was started in Nazareth by Father Shoufani, an Arab Greek Catholic Prelate. He brought together Christian Arabs and Islamic Arabs who felt that there was no place in the public dialogue for the positions they held in their hearts. Nazir Mgally, a journalist, shared with us:

We are Palestinian people. We are also part of the Israeli state. We suffer with the people in the West Bank. We suffer with the Israelis. We said we were the bridge, and we didn’t do it. . . . I felt the best way to stop the bloodshed was to return to our roots as human beings. I felt I needed to understand his [the Jewish persons] suffering. Maybe he will understand our suffering.

The Memory for Peace group began by studying Jewish history together, and, after some time, they invited Israeli Jews to study with them. Just weeks before we met with six members of this group, they had traveled together to Auschwitz, 150 Arab-Israelis and 150 Jewish-Israelis.

A Nazareth building contractor explained why, as an Arab, he went to Auschwitz:

We are living here together and recent events have hurt us. We’ve seen the Jewish people close down and distance themselves. We wanted to see the roots; wanted to go to the place of greatest disaster. Today we know the main problems of the Jews. The Jewish people have fear. They have always been chased. We want to support them. Our aim is holy. With all our might we want to bring together the people who are living here.

The next day we met with a small delegation led by Sheikh Abd Elsalem H. Manasra, the head of the Salam Qaderite Sufi Order in Jerusalem and the Holy Land. He explained that while Sufis are Muslim, their tradition differs from many other Islamic traditions in that they try to penetrate into the texts, rather than interpret them from above. In Arabic, the words “Islam”, “peace”, “surrender”, and “wholeness”, all have the same linguistic root. The Sheikh’s spiritual vision was open and embracing:

I’m speaking as a human being, as an Arab, and as the Muslim. I begin with human being. This is what I share with you. Everything else is less.

Sufis say they have the truth, but not the whole truth. Others have a truth as well.

The holy man gives peace to the earth. We should break down the borders in order to reach the man.

There are only two commandments: love of God and love of man. This is enough for a universal religion.

The holy land can include all the Palestinians and all the Jews, if we love.

Before leaving, the sheik taught us to rhythmically chant, in the Sufi style, the name Allah, the pronoun of God. We stood and joined together our voices and spirits: Buddhists, Jews, Christians, and Muslims, holding a sacred space together.

The retreat program in Nazareth, at the St. Gabriel’s Hotel, included elements from a standard mindfulness retreat, such as Dharma talks, sittings, and walking meditation, along with several public events. On Friday night, two hundred people sat in the church of St. Gabriel to listen to representatives from eight groups talk about their experiences working for reconciliation and peace. On Saturday afternoon, the retreat ended with a silent peace walk through Nazareth, to Mary’s well, in the heart of the city.

Often during the weekend, around meals and odd moments, Israeli Arabs, Israeli Jews, and members of the international community shared personal stories and reflections. In Hebrew, Arabic, and English, sometimes all three languages at once, people talked about their roots, their desire for peace, and their frustration with the distrust and fear that separated communities. Afterwards, both Israeli Arabs and Israeli Jews mentioned that this casual sharing from the heart, across customary boundaries, which had happened in Nazareth, was rare even at peace and reconciliation events.

Several days after the retreat, on my last full day in Israel, I sat with a Jewish Israeli friend talking about what I had seen and learned. I struggled to pull the parts together. When I talked about the spiritual lessons I had learned while in Israel, my comments centered on all that we gain when we let go of blaming. I felt I had gained insight into what Thay Phap An had said, that “Looking deeply is to be truly present, without blame or judgment.” When we blame we distort. When we blame we highlight an individual’s or group’s actions, we ignore the context, and we ignore the contributions we or others may have made to the situation. When blame is in my heart, the other person naturally becomes defensive. Communication breaks down. Authentic dialogue and reconciliation cannot occur.

And yet, a few minutes later, when I talked about the reality of daily life I had observed in Israel and the West Bank, I dwelled on the defects of Jewish Israeli society. In me were feelings of disappointment and anger. The distrust and institutional racism was more extensive than I had imagined. I asked my friend, “Of all people, after the experience of the Holocaust, how could Jewish people be so intolerant of Arab Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank? How could they be insensitive to their pain?”

For several hours we talked, working our way down to the roots of the incompatibility between what I was feeling and saying about Jewish Israeli society and my increased understanding of the corrosive effects of blaming. I shared with my friend that the trip had made me aware of how often blame crept into my thinking and speaking. To use words such as racism and intolerance almost automatically steers a conversation toward blaming. Often, however, it is much more subtle--spontaneous remarks directed at loved ones, and seemingly objective discussion of social issues which slip into blame. (How could you/they do that?)

Why was it so hard for me to let go of blame? For the next two months I pondered the question and talked about it with friends. Finally the realization came that in my life, in an odd way, blaming was connected to caring. When it seemed that someone else’s actions were causing pain to me or to those I cared about, my response was to blame them. When I acted in ways that seemed to undermine the goals I had set for myself, I blamed myself. When people close to me acted in ways other than what I thought was in their best interest, I blamed them. That was how I was raised.

My strong reaction to what I saw as Jewish Israeli insensitivities came out of a deep caring. I did not want that community, which had suffered so much, to be destroyed again. I deeply wanted Israeli Jews to act in ways I believed would lead to a just and lasting peace. I saw that in my reactive blaming I underplayed how debilitating the historical wounds might be (Who was I to judge that enough time had past?), and I underplayed how many causes and conditions from outside the Israeli-Jewish community contributed to what I perceived as Israeli-Jewish insensitivity to the pain of others.

For me, the great challenge, in Israel and elsewhere, is to let go of the blame and not let go of the caring. Without blame, we can still work and hope for peace. Without blame, we can still bring attention to situations of injustice. We can even ask people to act in a different way, or, when necessary, forcibly prevent some persons from hurting others. Without blame, rather than closed and angry, our hearts are open and accepting.