By Nandini Seth on

Nandini Seth shares a curriculum to teach young students how to deal with hurt, guilt, pain, and other difficult emotions.

Every morning, before I went to school, my mother read books to me. This was one of my favourite parts of the day. I would wake up and run to the pale green sofa in our living room,

By Nandini Seth on

Nandini Seth shares a curriculum to teach young students how to deal with hurt, guilt, pain, and other difficult emotions.

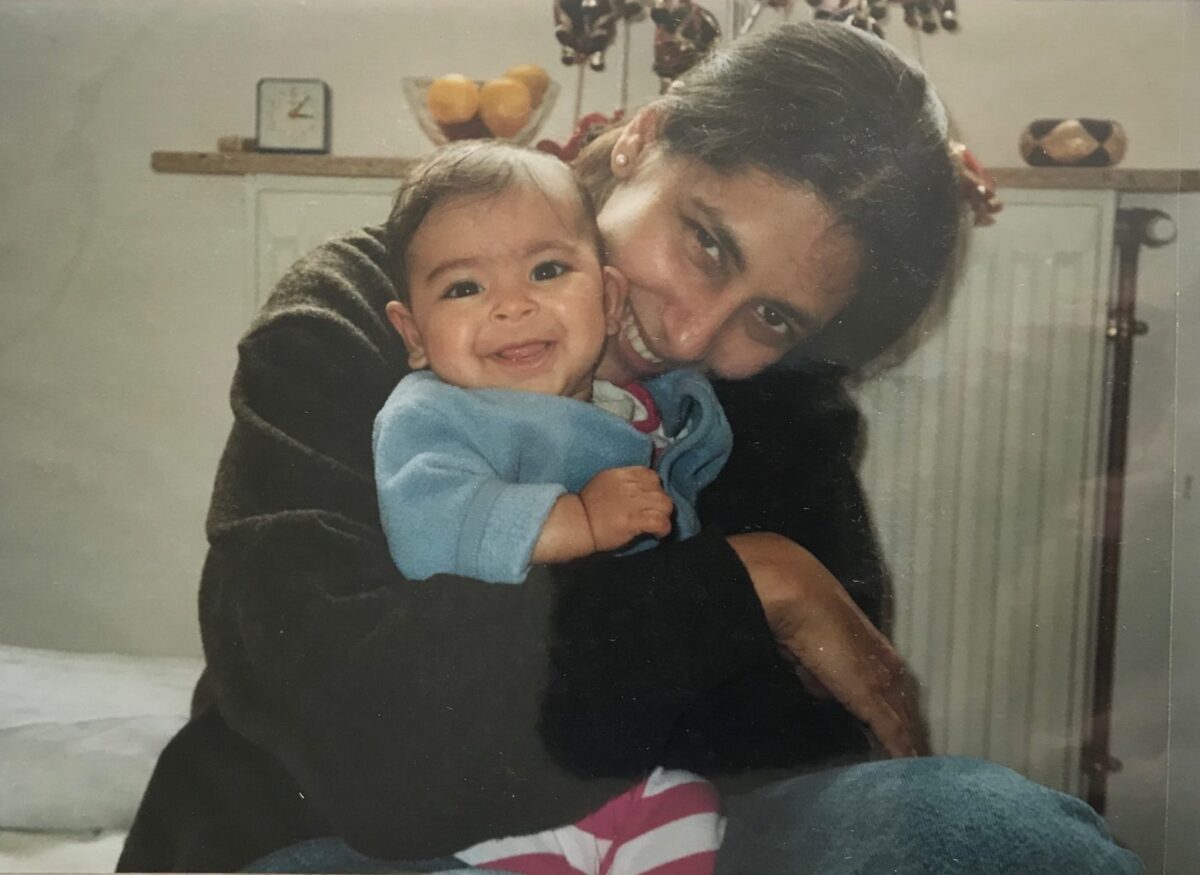

Every morning, before I went to school, my mother read books to me. This was one of my favourite parts of the day. I would wake up and run to the pale green sofa in our living room, where we would snuggle up with a glass of warm, sweet milk and read. Our explorations ranged from encyclopaedias about amethysts and artichokes to the Mahābhārata to a large number of Plum Village children’s books.

I have been visiting Plum Village since I was a three-month-old baby. Plum Village is where I took my first steps, where I had my first ice cream—it is my home. The Plum Village books I read in the mornings, from The Hermit and the Well to Anh’s Anger, took me back to Plum Village, which made me very happy. Additionally, unbeknownst to me, their simple stories and colourful drawings gave me deep teachings.

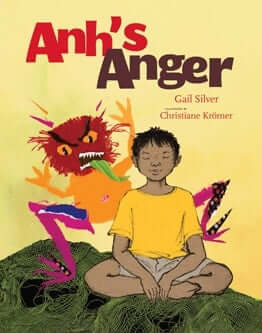

My favourite story growing up was always Anh’s Anger. This is a story about a boy named Anh who gets angry with his grandfather for interrupting his play time. Anh meets his anger (which appears to him as a giant monster). He talks, dances, and breathes with his anger, and they soon become friends. Anh learns to understand his anger. Though the anger frightened me a little bit, I loved this story and I loved dancing with my own anger, breathing deeply with it, and talking to it. It was exciting to think of my anger in this way; subconsciously, I was transforming my negative emotions. Later in life, confused about the more complex aspects of Buddhist psychology like seeds or manas, I would think about the drawing of Anh’s anger flailing around in my brain.

Though I have always loved school, at some point I realised that even with my many, many years of schooling, there were things I had not been taught. In university I was asked to create a fifth grade school curriculum. The first thing that came to mind was the gap in my education that stories like Anh’s Anger had filled. A gap in knowing how to deal with the hurt, guilt, pain, and other difficult emotions so present in our lives. I wrote a sixteen lesson curriculum that included the first four classes described below:

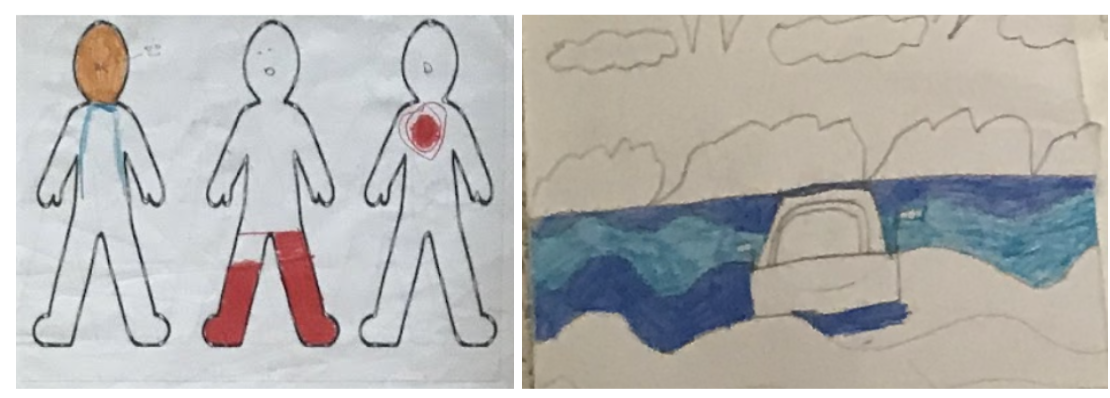

Day 1 Step 1: Ask the students to close their eyes and think about a moment that made them truly happy. Then ask them to feel that happiness in their body. Step 2: The children share the moment they thought about with the group. Step 3: Have them colour in the part of their body where they experience happiness, noticing and remembering how it feels and looks. Step 4: Repeat the process with anger, fear, sadness, and love. Homework: Students try to experience their emotions coming and going in their everyday lives. When they feel an emotion they can put a hand on the part of their body where they located the presence of this emotion.

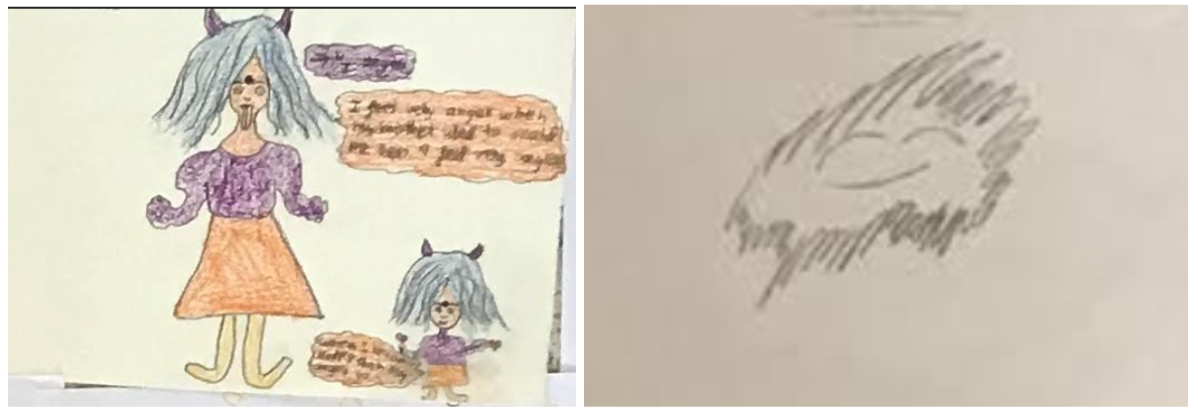

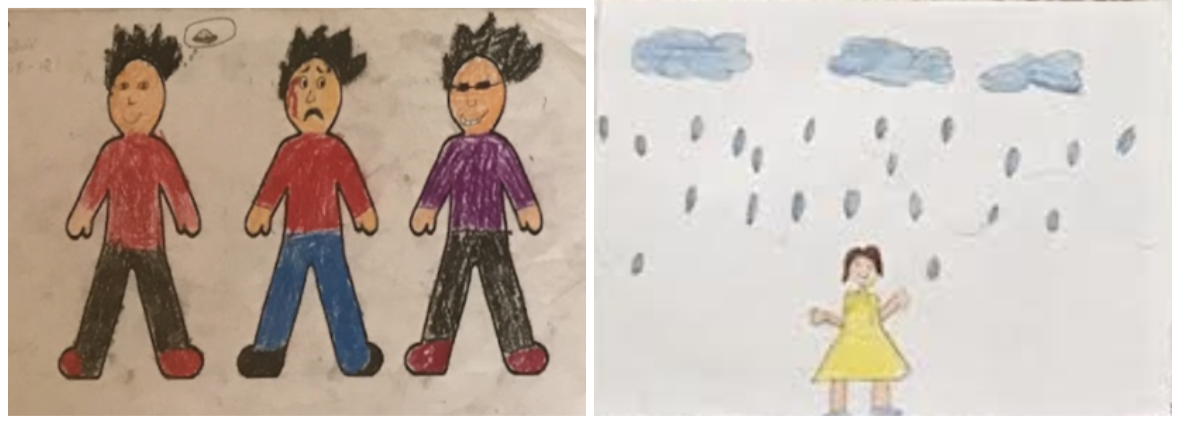

Day 2 Step 1: Read a book called Anh’s Anger to the students.1 Step 2: Ask the class to think about a moment when they felt angry. Identify the emotion, identify the circumstances, try to picture the emotion. Maybe students write down what they are thinking about. Step 3: Each child draws the emotion they felt in the situation they just thought about. (It’s difficult for a child to talk to their anger. Using art can help children have a mental image of a being to talk to.) Homework: Students watch the video “How to Let Anger Out” by Thích Nhất Hạnh.

Day 3 Step 1: Share a summary of the basic ideas of the video, “Taking Care of Anger” by Thích Nhất Hạnh. Step 2: Offer students a guided meditation to practise sitting with their anger, loving it, holding it like it’s a baby (as shared in the video), and looking at it deeply. Step 3: Students start a new drawing with the meditation, homework video, and the held anger in mind. They may draw their friend, anger. Homework: Students practise seeing their emotions come up and talking to them in a kind but firm way in their everyday lives.

Day 4 Step 1: Students discuss the homework of using the meditation practices to deal with strong emotions in real life—the difficulties and the joys. Step 2: Students work on both their drawings (the initial anger drawing and anger as a friend). Step 3: Students present their images and stories.

After I created the curriculum I wanted to share it. I wanted to see if what had helped me could be useful for other children. Working with Wake Up Schools and the wonderful Dr. Orlaith O’Sullivan, I offered these sessions to children between age five and fourteen from three different schools: the Tibetan Homes School, a school for Tibetan refugee children in the Himalayas; the Bajaj School for the Deaf, which offers free education to children with severe hearing disabilities; and Cambrian Hall, a school for middle-class, urban Indian children. Each group had a very different background and very different struggles. I wondered if the effect of the project would differ accordingly. I offered the sessions in a workshop style. My goal was to give something helpful to these children. I came away from the experience feeling very full. I have tried to describe what happened but have been unsuccessful. Instead of writing about my experience, I would like to share with you some of the drawings and stories I received after these sessions.

Tibetan Homes School

In their happy, sad, fearful stories of the Tibetan children, their parents were always present. These children ranged from five to nine years old and all except one lived far away from their parents. These children’s parents had sent them away from Tibet for a better, more free life. The children missed their families terribly. Surprisingly, they didn’t seem to feel much of a connection with anger. I adapted the curriculum to be about the sadness they felt when they missed their families. It was incredibly powerful to be with these children.

Student 1: Sometimes when I think of my parents I go to the bathroom and cry. Yesterday night I really missed them.

NS: Did you try to hug your sadness like the little boy did in the story?

Student 1: Yes. [Quietly.]

Cambrian Hall

The children in Cambrian Hall had a range of pains. Our discussions ranged from teasing and fights to death and bullying.

Student 2: I feel angry when my younger sister disturbs me when I study.

NS: Do you think about why it disturbs you?

Student 2: Hmm, maybe she wants to play with me? [Smiles a little.]

Student 3: I get very angry and sad in my heart when my parents beat me. [Silence in the class.] I also feel angry when my brother beats me.

Student 4: So do I.

Bajaj School for the Deaf

I had expected the deaf children to be the most unhappy, maybe to have feelings of insecurity or anger at the world for being so harsh on their disability. This was not the case at all. There was no resentment. Not one child in the deaf school, not one, mentioned their deafness or anything to do with it in a story of anger or sadness or fear. I found it particularly beautiful, working with the deaf children, to notice the way their emotions seemed much closer to the surface simply because instead of talking about how they were feeling they had to sign it. This impression was particularly strong when the children discussed their happy moments—it looked like they were dancing.

Student 5: I feel happy when I get food, I feel sad when I finish my food, I feel angry when I wait for food. [A bit cheeky this one.]

Student 6: I feel happy when my mother/sister/father/teacher/friend hugs me. [The number of children that talked about hugs was quite overwhelming.] I will hug my anger 🙂

This issue of The Mindfulness Bell is about Thầy’s lineage. I started out this essay talking about how Thầy gave me a physical home in the form of Plum Village when I was a child. Eating lunch with him are some of my most cherished and love-filled memories. But what strikes me about Thầy is that he has the power to give children he has never met, children who have never set foot in Plum Village, that same love, and a home in themselves. When I was doing this project and writing this article, the question that kept coming up for me was: Did the workshop work? Truthfully, I am not sure. What I do know, as cheesy as it sounds, is that Thầy’s lineage is in each of these children. His lineage is present every time they hug their anger or hold their sadness. And that is magical.

1 Kinder Studios, 2020, “Story Time: Anh’s Anger,” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7fLfnmvfBM