By Lan Phuong

When Daniel Milles told me about Thich Nhat Hanh’s retreat in the Paris area at the end of March, I was very surprised. There was some indication of a low interest for Thay’s teachings in France—his last retreat in Paris had taken place five years before; the French group at Plum Village each summer represented a tiny part of the community; and though Thay’s books are best-sellers in the U.S., they can be hard to find in Paris.

By Lan Phuong

When Daniel Milles told me about Thich Nhat Hanh's retreat in the Paris area at the end of March, I was very surprised. There was some indication of a low interest for Thay's teachings in France—his last retreat in Paris had taken place five years before; the French group at Plum Village each summer represented a tiny part of the community; and though Thay's books are best-sellers in the U.S., they can be hard to find in Paris. But then I learned that this retreat was almost fully booked, and more than a thousand people were expected for his two Dharma talks. Once more, I realized the futility of holding onto beliefs and opinions.

As I drove to the retreat at Bois le Roi, the afternoon sun and clouds were playing hide-and-seek, and the highways were jammed. I had to make an effort to remain calm. At one point, a road sign caught my attention—the "Bonsai Hotel" promised serenity to anyone taking refuge within its walls. I smiled and began to relax. Then I remembered Thay's basic teaching: the practice of mindfulness at every moment, necessary to counterbalance what French surrealist writer Andre Breton calls "la poursuite eperdue"—the energy that propels you into the future or makes you indulge in the past. According to Breton, this energy is a flight in response to fear and existential anxiety. For the time being, it was depriving me of a precious moment of my life as I drove to the retreat with someone I loved, surrounded by a paradise of color and form.

I began to understand that the retreat had already begun: being in retreat means to stop, let go of worldly goals, and disentangle oneself from patterns and habits which can make one live in forgetfulness.

The arrival at the retreat turned into a celebration: all my Plum Village friends were there, fresh and serene despite tiring trips from Paris, the Dordogne, and abroad. The place was pleasant and welcoming—nearby, a lake and riding school attracted all the children. Final preparations were well under way. Melodie took my hand and together we led the newcomers to their rooms. A shuttle was being organized to pick up those arriving by train. People met, others recognized old friends, and the invisible network of Thay's friends was very alive.

While waiting for Thay's introductory talk, Brother Doji led us in a silent meal. The quality of the silence at the meal became a good way to measure people's absorption in the retreat. Already the next day, we noticed that the restaurant staff was becoming more silent and mindful. Even the music seemed to adapt to our rhythm!

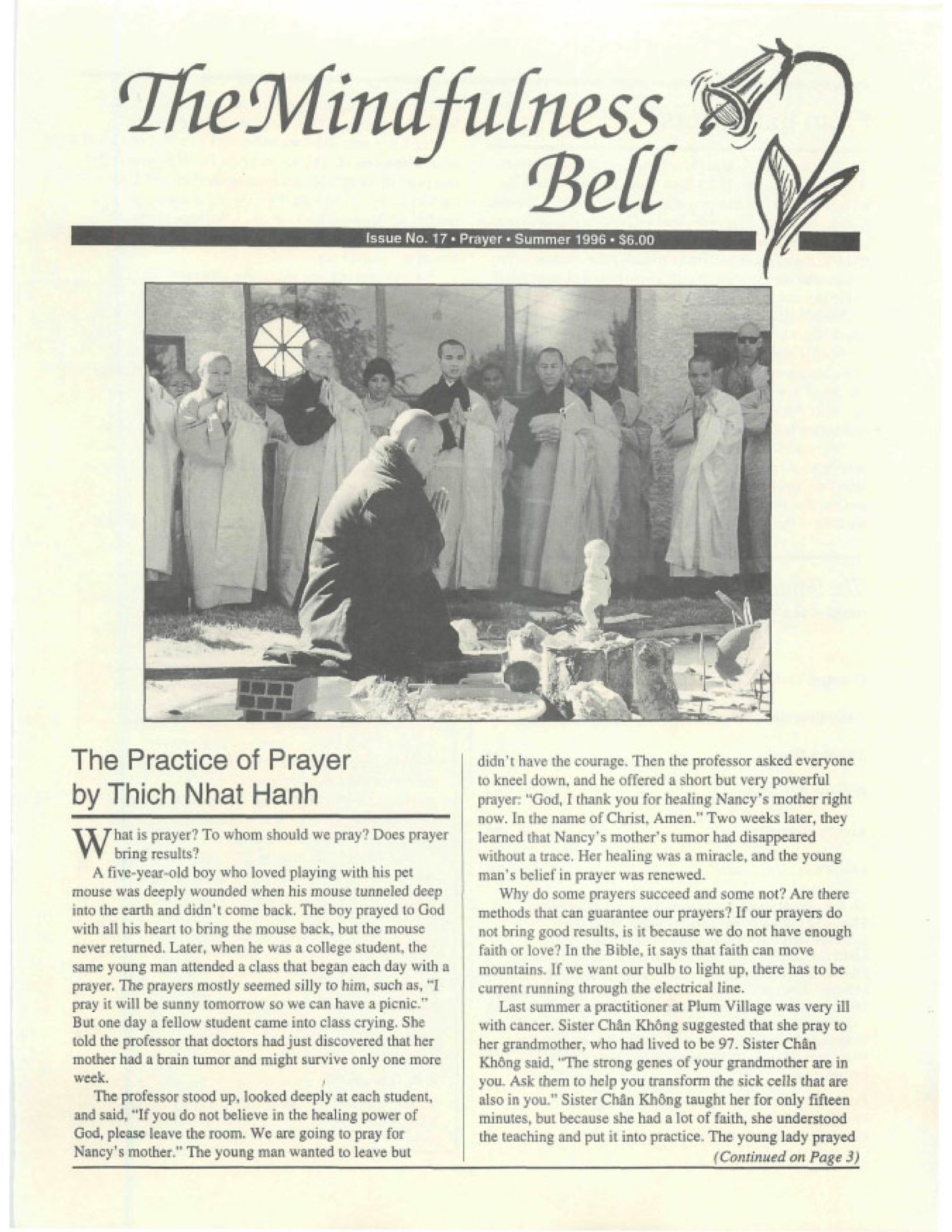

Thay's public talk took place in the grand room of the castle, the wooden panels of its walls and ceiling decorated with lys, the flower symbolizing royalty. Thay seemed particularly happy to express himself in French in front of a large gathering of receptive people. His first words were a little hesitant, as he does not have many opportunities to speak the language, but soon they flowed and he cited the French writers and poets of his youth.

Through the examples of a flower, a breath, and a wave, Thay taught both how easy and how difficult the practice of mindfulness can be. He demonstrated how to walk in a joyful and steady way, thus becoming a source of inspiration to others. Thay told us that joy is the fruit of mindfulness practice and is available to us all the time—when we feel, see, smell, hear, and touch. Thay also asked us to find the true master, who can help us touch the inner master. We will find him when we fully trust the practice.

Everyone entered the retreat with their whole being. From the very beginning, the atmosphere was focused and the program followed in a precise way: sitting and walking meditation, silent meals, Thay's talks, and Dharma discussion groups. Sangha-building groups were organized in response to Thay's wish that his students form local Sanghas. These groups worked hard and obtained fruitful results. People shared their experiences and realized that, although they came from very different horizons, they had much in common.

The conclusion of the retreat was not an end, but a continuation, demonstrating the relativity of every cessation. Most of us met again the next few days at La Mutuelite conference hall in Paris to listen to two beautiful talks. These provided the impetus for many of us to gather the following Sunday for a Day of Mindfulness at Fleur de Cactus, the Sangha house on the bank of the Marne River. In Paris, a new meditation group started in the wake of these events, adding a stone in our Zen garden.

Lan Phuong, Root Mountain of the Heart, is a college student in Paris and also translates at Plum Village.