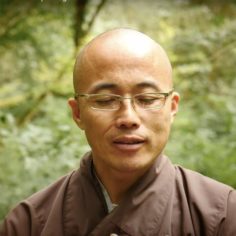

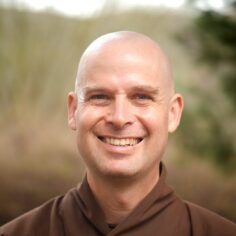

By Brother Pháp Dung, Brother Pháp Lưu on

An interview with Thích Giác Quang, a Most Venerable from Huế, Vietnam and a great supporter of Thầy and the Plum Village tradition, exploring the importance of the many ceremonies remembering and honoring Thầy’s passing.

Brother Pháp Lưu: We are deeply moved when you speak about our Teacher, his love,

By Brother Pháp Dung, Brother Pháp Lưu on

An interview with Thích Giác Quang, a Most Venerable from Huế, Vietnam and a great supporter of Thầy and the Plum Village tradition, exploring the importance of the many ceremonies remembering and honoring Thầy’s passing.

Brother Pháp Lưu: We are deeply moved when you speak about our Teacher, his love, his path, and his teaching. Many Westerners ask, “Why is there a ceremony on the first anniversary of Thầy’s passing [Lễ Tiểu Tường] in Vietnam?” What is the meaning behind the Cremation Ceremony [Lễ Trà Tỳ], the forty-nine-day ceremony, the hundred-day ceremony, the Smaller Memorial Ceremony on the first anniversary of Thầy’s passing [Lễ Tiểu Tường], and the Grand Memorial Ceremony [on the second anniversary, Lễ Đại Tường]?

Brother Pháp Dung: Many practitioners living abroad follow our Teacher, they love our Teacher very much. They have been following our ceremonies online over the past year, and they write very touching letters commemorating Thầy. Still, they don’t understand much about the culture and ways of Vietnamese people, especially Buddhism. Pháp Lưu and I could go to the library to research, but on this occasion we have you. Aware of your experience and your love for our Teacher, we wish to hear directly from you about the culture and your feelings during these ceremonies. We’ve heard from other monks that, thanks to your help, these ceremonies were realized in the spirit of Thầy’s teaching and the Plum Village tradition. The anniversary ceremonies will affect our worldwide Sangha. I feel that during the next five to ten years, many Westerners will begin to go on pilgrimage to places like Huế, Vietnam. We hope you will share your personal insights into the meaning of the ceremonies. The first question I would like to ask:

In Buddhist culture, Vietnamese culture, when a great master passes away why are there ceremonies? Why must there be so many stages of ceremonies?

Thích Giác Quang: Generally speaking, the cultures of East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea), and Vietnamese culture in particular, greatly respect the deceased. Vietnam is influenced by China. When Chinese culture was introduced in Vietnam, [neo-Confucian] ceremonies were mainly used to bolster the national culture. We, as Buddhists, never go against that tendency, but we add Vietnamese Buddhist content to the ceremonies. Buddhism has always done like this [integrating into the local culture], as did the Buddha.

After the death of a layperson, we first hold the Purification Ceremony: cleaning the coffin, chanting prayers, sprinkling water for purification. Then comes the Coffin Closing Ceremony—putting the corpse into the coffin, done very carefully, respecting the body. They place precious materials, and sometimes clothes and personal possessions, in the coffin.

In Buddhist practice, we have the Opening Scripture Ceremony, in which we offer homage to Buddha, asking Buddha for permission to start chanting the scriptures for prayer. Next is the Soul Return Ceremony [inviting the soul back]; when a person dies, their three souls [三魂] and seven spirits [七魄] have left, so we invite them back. After that is the Paying Respects Ceremony to honor the deceased. In the following days, we prepare daily meal offerings. Then, before the funeral day, there is the Morning Ceremony. That morning, we offer a meal to the departed spirit and report that we will escort them tomorrow. The day of the Morning Ceremony, we also invite the departed spirit to pay respects to the grandparents, the ancestors. As a descendant, the deceased is coming to enter the lineage of the ancestors who have gone before.

The next afternoon there is a Requiem Ceremony and an Evening Ceremony. The special feature of the Evening Ceremony is that all descendants are present for a joint offering. It is like when parents go far away, and children come to give gifts and bid their parents farewell.

The next day is the funeral day when we offer the Departure Ceremony, to inform the departed spirit that today is a good day to escort them along their way. When escorting the deceased, laypeople may participate in a Coffin Closing Ceremony. Then, there is a Grave Purification Ceremony, when monks stand to purify the grave before lowering the coffin into the burial place. [In the case of Thầy, we cremated his body instead of burying it, which is still an unusual procedure in Vietnam.]

Coming home, we hold the Soul Return Ceremony. We bring the departed spirit home and establish it on the altar. The folk consider the incense burner as the dwelling place of the departed spirit, so we set up an incense burner on the altar.

We conclude with the Completion Ceremony: chanting scriptures and paying homage to Buddha.

After the funeral and burial or cremation, the deceased’s name tablet is placed on the ancestral altar in a ceremony known as the An Vị Bát Hương of the deceased. An image of the deceased is placed on the altar and incense are offered.

Afterward, the first week is counted—from the day of death to the seventh day. This cycle is repeated weekly. According to Chinese culture, a person who has passed away must go through ten stages, known as the Ten Courts of Hell, where they are judged in a court of law. In one of these courts, the King of Hell transmits your case to the judge. In Buddhism, our ancestors still accept the concept of the ten courts from folk beliefs, but they use them to infuse meaning and content into ten ceremonies. For example, in the Sutra of Good Birth [the Siṅgāla Sutta in the Pali Canon], the Buddha asked Good Birth how many directions he bows to each day, and what is the purpose of his bowing. Good Birth did not know, he simply followed what his parents taught him, so the Buddha taught him to whom he should bow in each direction. Therefore, each bow has a meaning, and bowing becomes complete.

We still accept the concept of the ten courts, but we add content and meaning to them. Each week has a purpose: so descendants can remember their ancestors. Descendants gather to practice or cultivate the wish to pray. This is perfectly fine, there are no obstacles at all.

In the seven weeks after burial, there are seven stages where we chant sutras every day, perform good deeds, and pray for the deceased. Whether on the spiritual path or out in the world, we direct our minds toward our loved ones.

The one hundredth day after the deceased passes is called the eighth stage, the first anniversary is the ninth stage, and the second anniversary is the tenth stage. The first anniversary is exactly twelve months after death. The second anniversary is the Grand Memorial Ceremony at twenty-four months after death. After that, annual commemorations are observed.

When the ceremony proceeds in two lines, it is a ceremonial formality, influenced by ancient rituals. Walking in two lines represents solemnity. Funerals in Huế are the most elaborate. In the South, funerals include music, singing, alcohol, and food, depending on the customs of the region.

Thầy’s ceremonies are influenced by the culture of the royal court, the culture of the temples, and the inscriptions at the temples. There is a ceremonial procession, walking in two lines, showing respect and solemnity.

PD: Dear Most Venerable, we hear that on the second anniversary, the Grand Memorial Ceremony [Lễ Đại Tường] is very important. Why is that?

GQ: Normally, after the Grand Memorial Ceremony, it is considered that Thầy is no longer. Before that, we feel Thầy is still here. For two years after Thầy passes away, if anyone is worthy to be abbot, that person would not yet become abbot. For those two years, it’s like Thầy is still here. For example, in the Gratitude Geat Precepts Transmission Ceremony [Đại Giới Đàn Ân Nghĩa in 2016], Thầy was sick, but we could still carry out the things we needed to do, because Thầy was still sitting there protecting us, nurturing us with his solidity.

For two years after Thầy passed away, the one preparing to be abbot is only seen as a Temple Supervisor, meaning they just watch over and manage the temple! The good thing about this is the brothers are not disturbed because Thầy is still sitting there. The brothers are still united. After two years, everything is in order, and then that elder monk officially becomes the abbot. The Grand Memorial Ceremony’s meaning is the same! It’s the time of parting between teacher and student; all disciples, children, grandchildren gather back home. After the Grand Memorial Ceremony, there are only anniversary ceremonies.

PL: Why must all senior disciples return for Thầy’s Grand Memorial Ceremony?

GQ: The elders are significant, so they must be present at the service. In Vietnam, we have a saying: “If you play the role of an older sibling, you must bear the responsibility.” As elder brothers or sisters, we have a duty to care for our teacher; as elder siblings, we need to be the first ones to take responsibility.

PL: After Thầy passed away, you mentioned that the connection between Plum Village and our root temple is very crucial. Could you tell us why this connection is necessary and why it’s so important?

GQ: Plum Village and Từ Hiếu are inseparable, like one body. The first time I brought my disciples to Từ Hiếu, I told them coming here is like returning to their spiritual homeland. They were still very immature, and I worried that they might upset the Most Venerables. If they had any questions, I told them, they should ask the Most Venerables directly for guidance. I would never have dared to instruct them on my own. Regardless of which country they come from, Từ Hiếu Temple is their spiritual homeland. This deep connection was reflected in Thầy’s teachings. Toward the end of his life, Thầy returned to Từ Hiếu, inviting his disciples to join him. It is natural for us to feel connected to Từ Hiếu, and even when unexpected things happen, we always acknowledge Từ Hiếu as our root.

When a person passes away, over time their memory may fade, but with Thầy, things will gradually become clearer. For instance, Harvard University now includes mindfulness meditation in its curriculum. Bhutan, the happiest country in the world, has used Thầy’s image on their stamps. There are countless other examples. A Vietnamese Buddhist monk in America suddenly saw Thầy’s greatness clearly. He realized that, although he was highly educated, fluent in English, and had profound knowledge of Buddhist teachings, he could not achieve what Thầy did. He simply couldn’t communicate with everyone like Thầy. These examples make the vast scope of Thầy’s teachings evident.

In the future, the world will recognize Thầy as a global spiritual teacher. How could his path ever fade? Plum Village may experience ups and downs. Though people may worry, this is normal. Any organization experiences this. However, when something becomes a truth, a reality, it will never go up and down. For example, the philosophy of Laozi may not have many followers now, but no one can erase his ideas, nor those of Confucius, let alone the teachings of Thầy. Even if Plum Village experiences ups and downs, its teachings and practice will remain stable. In the future, people will recognize Thầy as a global spiritual teacher, and hearing this makes me very happy.

Even the books teachers have written about Thầy make the readers perceive the light of Vietnamese Buddhism more vividly. Normally, we are confined within the scope of Vietnam, but now Thầy’s teachings have become global, and his disciples are from all over the world. They speak Western languages, Chinese, and so on. We have monks and an international monastic organization. During a visit to Plum Village, I once shared that the greatness of a person who transmits the teachings is to help local people become Buddhist monastics. The most beautiful thing about our practice centers abroad is that the non-Vietnamese now outnumber the Vietnamese. In our center in Thailand, there are over ten Thai nuns. Sister Linh Nghiêm is currently the eldest among the Thai nuns practicing in the Plum Village tradition. There is a close bond between Vietnam and Thailand, all thanks to Thầy. [Laughs]

PD: Thank you very much, Venerable!

These excerpts were taken from an interview conducted at Thai Plum Village on February 7, 2023 by Brother Pháp Khâm, Brother Pháp Dung, Brother Pháp Lưu, and Sister Linh Nghiêm. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and ease of reading.