By Wendy Johnson in August 1992

On the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day, His Holiness the Dalai Lama offered four reasons for us to be hopeful: the dedication to nonviolence in such violent times, the strength of the individual in the face of adversity, the arising of religious life, and an awakening to our connection with our environment.

The deepest response I know to what is happening to our world through our own carelessness,

By Wendy Johnson in August 1992

On the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day, His Holiness the Dalai Lama offered four reasons for us to be hopeful: the dedication to nonviolence in such violent times, the strength of the individual in the face of adversity, the arising of religious life, and an awakening to our connection with our environment.

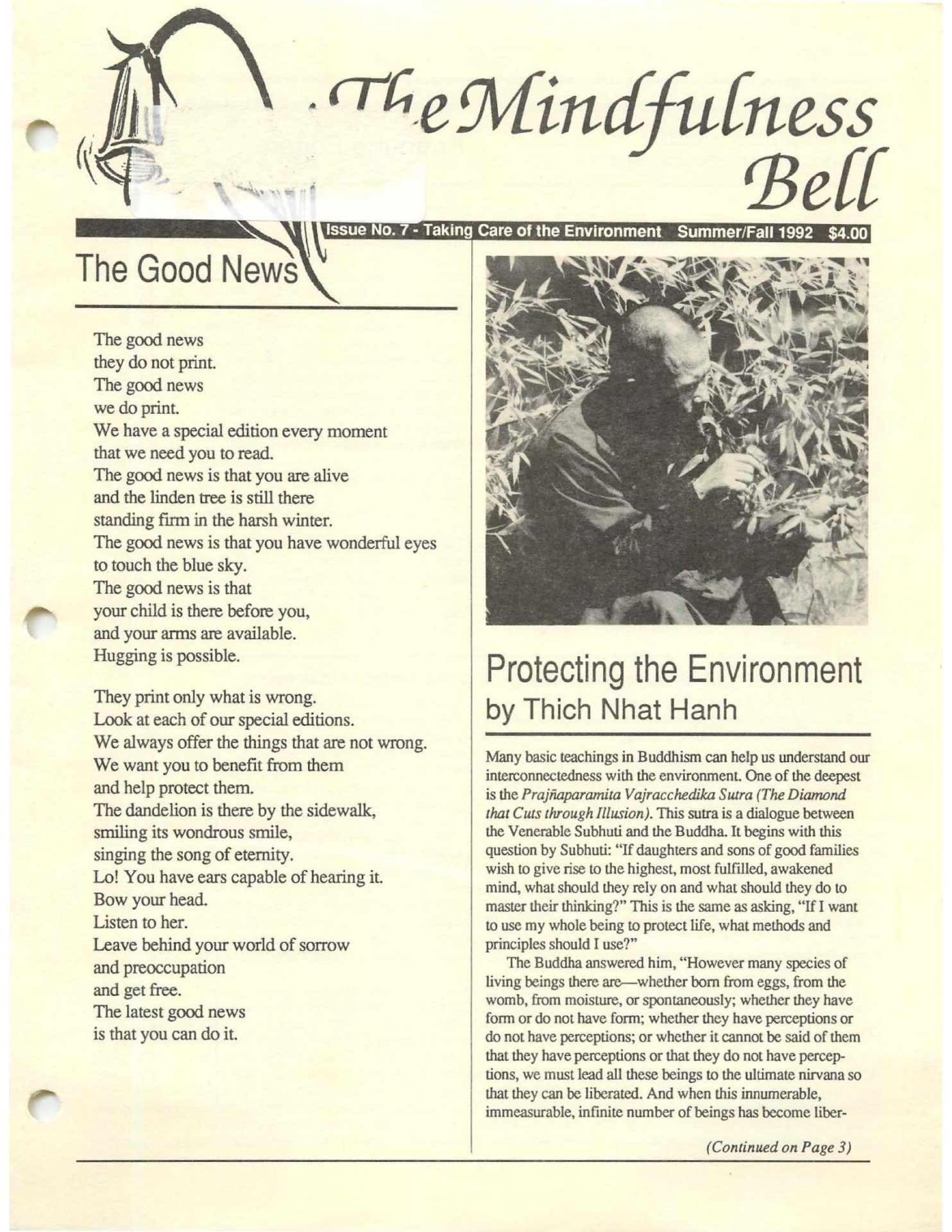

The deepest response I know to what is happening to our world through our own carelessness, greed, and confusion is the response of Shakyamuni Buddha to Lord Mara 2,500 years ago. When asked by what right, at whose invitation, he was allowed to sit in meditation beneath the Tree of Awakening, the Buddha responded by extending his right hand and touching the Earth. This image of an awakened being sitting beneath an ancient shade tree and touching the Earth, calling on the Earth to be his witness, is an image of guidance and strength for our times. In some iconographic representations of the Earth-touching mudra, the Earth rises up to meet the Buddha in the form of a female Earth goddess. This image is vital because it illustrates the mutual connection between one who loves the Earth and the Earth herself.

We live in a unique time in world history. An area of tropical rainforest the size of a football field is destroyed every second. By the end of this century, an estimated one million plant and animal species will have become extinct. And we are witness to so much human suffering, as evidenced in the turmoil of south-central Los Angeles in early May. Yet we also know that we have the ability to do something about the situation facing our world. Despite this, we act as if both the problems and our ability to address them are not real. These are times that call us to look deeply at what we are doing and to come into direct connection with our Earth, just as Shakyamuni Buddha did when he called upon the Earth to be his witness by touching the soil with his right hand and feeling the spirit of the Earth respond. Only by looking deeply and sustaining our gaze, even though this may be painful or difficult, can we discover our common work, how we can serve.

"Turn towards the world and try and articulate it, for that is what the ancients did as long as they were alive. Every excellent endeavor turns from within toward the world." These words, spoken by Goethe more than 100 years ago, are guideposts for action in our times. Every excellent endeavor turns from the self outward, since we are connected in every way. The study of ecology focuses on habitation, on the relationship of organisms. The Greek root of the word "ecology" is oikos, meaning home or dwelling. We are speaking of inhabiting our world, our neighborhood, our Earth, as our home. And this inhabitation is characterized by passionate, steady involvement in what we love. When I consider the work of taking care of our Earth and of each other, I feel that we are taking marriage vows: Know one another in every way. Love, honor, and protect one another. And take risks together in order to bring back into balance what has been disturbed. Here are some standards that arise when I consider the ecology of caring for our world:

1. Fall in love with the Earth, the land, the place you inhabit. Be corrected by affection. Be guided by connection. Look deeply, touch the Earth. In ancient Hebrew, Adama means soil or red Earth. Adama gives rise to the word for human being, man: "Adam." So the first human being could also be called, "son or daughter of the red Earth." In English this loving connection is found in the correspondence between "humus" (fertile Earth) and "human," and it is expressed in humility, or loving connection. Lest we get too human-centered, please remember that there are more microorganisms in half a cup of fertile Earth than human beings on the planet. These microorganisms create the soil that sustains our life.

2. Look deeply at where you live. Know your place in every way so that you understand how to act. Those of us living in urban areas can also commit our energy to connecting with where we live. Notice when the trees on your street bud out and burst into flower, when the birds arrive and depart, and when they sing and fall silent. Notice how the rain runs away after a storm. And notice how you feel when you slow down enough to pay this kind of attention. Some of the most inspiring grass-roots work is now being done by committed people in urban areas joining together to create community gardens—gardens for the homeless as in Santa Cruz, California; gardens for the blind, for the terminally ill, for people with AIDS; gardens for children; and gardens for the comfort and integration of diverse, cultural populations.

3. Use your imagination! Be a practical dreamer, one committed to never stepping into the same garden twice, and one committed to knowing your limits and boundaries. Then watch these boundaries change and be redefined by your effort. Liberty Hyde Bailey called on American agriculture at the birth of the twentieth century to "create a system which relies on thought, ingenuity, care, personal involvement, and technology." This means a direct application of mindfulness, infused with the spirit and dedication of imagination.

4. Learn from your children and teach them what you know. Together, create and build sangha. Every year the resident children of Green Gulch Farm Zen Center come together to make dry flower wreaths from the Green Gulch garden. They sell these wreaths and donate all their earnings to help support a poor family in Vietnam. Over the years a real connection has grown up between the Green Gulch children and the family they sponsor. This year the Zen Center children visited a shelter for the homeless and spent an evening teaching wreath-making to twenty children there. In the Eel River region of northern California, a citizen advisory council has been formed to consider a complex array of environmental issues: two high school students are very active members of the Board of Directors of this citizens' council. There are many more instances of young people engaging in our world, thoroughly and inventively, finding ways to make a difference. I hope that every healthy association of friends and people committed to engagement with our world will have active participation from younger children. In this way we form an ecology of consciousness. We can actually grow our awareness just as we grow a garden. In ancient Japan, a community of practitioners living together and studying the Dharma was called sorin, "a forest thicket." This is a wonderful image for the modem world where we must learn to live together in harmony and difference, like the distinct and interdependent trees of a forest thicket sangha.

5. Whenever possible. become downwardly mobile. Find your true pace. enjoy your life. When a piece of Earth grows tired and loses fertility, it is restored by fallowing, or letting it rest for a season. The word "sabbatical" comes from the respected practice of dropping usual responsibilities and taking time to develop your deeper interests. Sabbath is the day of rest, the lazy day around which the week revolves. So land that is fallowed is land that is allowed to be wild and uncultivated, land allowed to rest; for out of this rest period, great fertility results.

"You never know what is enough," said William Blake, "until you know what is more than enough." The pace of the modern world has shown us what is more than enough. Therefore, it is a vital and radical act to slow down. In order to look deeply at our world, to touch the Earth and to sustain our gaze, we must prepare ourselves by living in the present moment and by finding our true pace. Real sustainability depends on a healthy body and mind; therefore, in taking up the challenge of our times, be flexible and bold. A sense of humor helps a lot. So do good friends and the ability to be fallow when you need to. Let love for this world be your context, your food, your spiritual source. Directed by real love, even in the presence of great fear and pain, put out your hand and touch the Earth. Look deeply, sustain the gaze, and out of awakened mindfulness, take up the work you are called to do at this time.

Wendy Johnson is the head gardener at Green Gulch, near San Francisco, and a Dharma Teacher in the Tiep Hien Order.