By Marjorie Markus

When I first heard that Thich Nhat Hanh would be leading retreats in Israel in May 1997, I was excited and knew immediately that I wanted to go. As the time approached to commit to attending the retreat, I had some doubts and concerns, particularly about how we might be received in Israel. It was the period when the peace process had become endangered, and I was concerned about our safety. After acknowledging these fears,

By Marjorie Markus

When I first heard that Thich Nhat Hanh would be leading retreats in Israel in May 1997, I was excited and knew immediately that I wanted to go. As the time approached to commit to attending the retreat, I had some doubts and concerns, particularly about how we might be received in Israel. It was the period when the peace process had become endangered, and I was concerned about our safety. After acknowledging these fears, my initial enthusiasm returned and I knew that I wanted to be present when Thay offered his peaceful presence and precious teachings to the people of Israel.

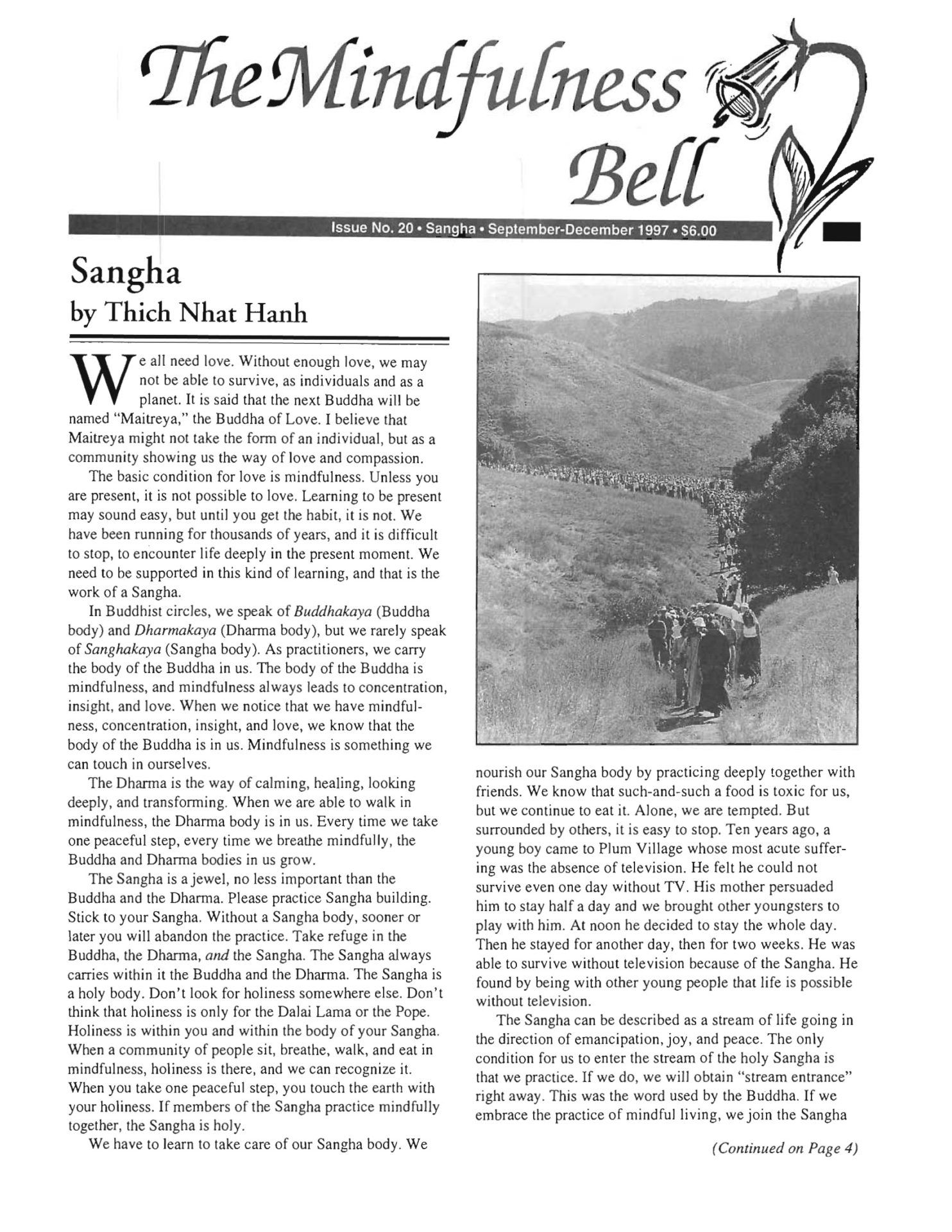

As Dharma teacher Lyn Fine and I drove from Ben Gurion Airport to Kibbutz Harel, I noticed a huge sunflower field in which only one flower had rushed to bloom, as if to greet us. In other ways, the land reminded me of Plum Village. The birdsongs surrounded us, and I instantly felt at home. The first person Lyn and I met at the kibbutz was Barry Sheridan, the coordinator for special events. He put us at ease, and throughout our visit was our mindful guardian angel. That evening, Thay, Sister Chan Khong, two monks, and four nuns arrived from Plum Village. For the next day and a half, final arrangements were made to welcome the more than 200 retreatants.

During Thay's introductory talk for the first retreat, the atmosphere was calm and quiet with people taking in his every word and gesture. They were relaxed and already smiling. The next day during the outdoor walking meditation, Thay continued to share the Dhanna as we gathered under the welcoming shade of a huge Jerusalem pine.

Over the course of his 11-day visit, Thay gave three more Dharma talks and another weekend retreat. I was touched by his commitment to our new Israeli Sangha. The retreatants came from diverse backgrounds. Some were young people who, like many Israelis, had traveled to India and other points east after their army service. Many had experience with vipassana meditation. A group of observant Jews came with their rabbi. They substItuted their morning prayers for the morning meditation, and time was set aside for their Shabbat observance.

The Dharma discussion groups reflected the retreatants' concerns about tensions between Israelis and Palestinians and divisions within the Jewish communities. Throughout the Dharma talks, Thay addressed these issues in many ways. Early on, he said, "It is through my background of suffering that I can understand your suffering." In another talk he said, "People have different ideas. Also, nations may be attached to their ideology. What is your idea of happiness? Maybe your idea of happiness is the obstacle to your happiness." He later said, "All of us have suffered violence. We ask ourselves where violence comes from. If we look deeply, we see that it comes from ourselves, because there is a bomb in each of us. Do we know how to defuse the bomb in us? That is the art. That is the practice." He suggested that each person sign a peace treaty with themselves and said the solution will come "from our lucidity, our happiness, our peace. When I have peace, it is easy for me to make peace."

Thay explained, "It is not my intention to uproot people. A person should remain a Jew, but that does not mean you have to accept everything in the tradition. Like a plum tree sometimes needs pruning. Otherwise it will be broken and will not be able to offer fruit."

In the question-and-answer session, Thay responded to a question about how to bring about peace by saying he is more interested in how individuals conduct their daily lives rather than in big solutions. When people with the same kind of suffering come together, they can exchange experiences and provide their nation with some insight. If they are able to practice deep listening and speak to each other in a calm voice, they may provide hope to others. He suggested inviting groups from different segments of the population to come together as the first step.

Dharma discussion groups had been organized by place of residence. Some made plans to meet again back home as a Sangha. Lyn Fine shared her experience in Sangha building with about 50 people interested in starting Sanghas. It was wonderful to see Sangha seeds being planted in Israeli soil.

Later that evening, enjoying the stillness of the kibbutz, I was delighted to find out that Thay and his Plum Village Sangha took the opportunity to visit Jerusalem. They arrived at the Western Wall in time to witness the fin al observances on the Sabbath. I imagined their joy while viewing the Jerusalem stones bathing in the setting sunlight.

At the Day of Mindfulness for peace and social change activists, Thay talked about "burnout" and said, "As long as love is still alive in us, we will not give up." He held out the reality that in each group there needs to be a person with presence. "Who is that person? You! You are the bodhisattva that can bring salvation, cultivate non-fear, and be solid." He added, "The question is not what to do, but knowing what not to do . If you operate on the basis of fear, you are not operating from the ground of peace. In our daily life, we have to live in a way that transforms fear and anger into compassion. With hatred, jealousy, and anger, there is no way to be a real social activist. The main task of a peace and social activist is to cultivate compassion, understanding, and patience. Patience is an indicator of love."

After a walking meditation through the pines, palms, and cypresses of the kibbutz, and a silent dinner, we gathered in the meditation hall for questions and answers with Sister Chan Khong. She shared her experiences as an activist during the war in Vietnam. The Israeli activists hung on to her every word, engrossed by what she had to say and the gentle strength with which she said it. It was as though they were right there with her in Vietnam, observing her as she used her mindfulness to remain calm, compassionate, and skillful while resolving seemingly impossible situations. She was a model of the quality of presence that Thay had talked about.

The next week, Thay gave three evening talks. At the end of each lecture, Sister Chan Khong captivated the audience with her singing, and no one wanted to leave. At the talk in Jerusalem at Kol Haneshama Synagogue, she spoke directly to the young people present. She shared breathing awareness with one young boy and gave him an opportunity to invite the bell to sound. The children left the room with big smiles. Shortly thereafter, the English language Jerusalem Post published an article about mindfulness' practice with children.

On the last night of the second retreat, Thay invited us to join him for a full moon walking meditation after the Dharma talk. This extra gift was gratefully accepted.

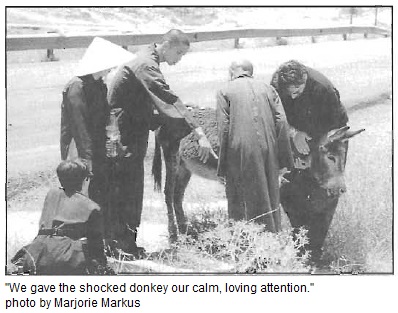

In our spare time between events, Thay and the nuns and monks took every opportunity to familiarize themselves with Israeli life. We visited a marketplace in a small town as well as those in the various quarters in the Old City of Jerusalem. We went to a nearby nursery with the kibbutz gardener, where we were surrounded by hundreds of exotic succulents, many of which displayed their fresh flowers. Everyone bought a plant to take back to Plum Village. We did floating and frolicking meditation in the Dead Sea. Sister Chan Khong was the first one in and the last one out of this saltiest of waters. On the way back through the desert, we saw a donkey get hit by a truck. Our three cars stopped, and we gave the shocked donkey our calm, loving attention. One of the nuns wet her brown scarf and tied it around his injured leg. We waited until a Bedouin boy appeared and walked our new Sangha friend to safety.

After Thay's last talk in Tel Aviv, we headed back to the kibbutz. We arrived after midnight, and Sister Chan Khong, still full of energy, joyfully told us that Thay had invited us to join him early the next morning on a silent walking meditation in Jerusalem. We would go to the Dome of the Rock, the Western Wall, and then walk in the footsteps of Jesus along the Fourteen Stations of the Cross. After many centuries of divisions, it was an opportunity to plant peaceful steps on the sacred ground of three major religions.

The next morning, we embarked on our last journey together as a traveling Sangha. Leaving the kibbutz, we passed the fie ld of sunflowers now in full bloom, and I thought of all the wonderful seeds planted during these two weeks. May they bear much fruit and benefit all beings. Shalom!

Marjorie Markus, True Contemplation of Understanding, practices with the New York Metropolitan Community of Mindfulness.

Peace Is Every Step

During the two retreats with Thay and Sister Chan Khong at Kibbutz Harel in Israel, we gained the serenity of dwelling in the preset moment. Hundreds came together, learned to breathe mindfully, and become bodhisattvas for one another. Sanghas will emerge.

That is not to say that everything was sweetness and light. Repeatedly, we were challenged to confront our prejudices, hatreds, and fears, and encouraged to find new places in our hearts from which to deal with them. Through "Touching the Earth," Sister Chan Khong encouraged reconciliation with all who have dwelled on this disputed land; Christians, Muslims, Jews, Arabs, Israelis. We were asked to learn to loved and understand the rapist sea pirate, in addition to sympathizing with his victims. This challenge resonates here, where terrorists and freedom fighters, bombers and suicide bombers, assassins and rival armies have shed so much innocent blood in both the immediate and historical past.

While peace will not come easily to this region, it was wonderful that so many peaceful steps were taken here.

--Robbie Heffernan, Amman, Jordan