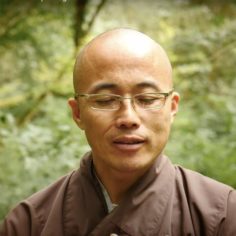

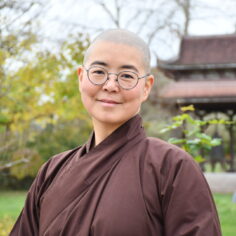

An Interview with Sister Trai Nghiem

By Brother Pháp Dung, Brother Phap Lai, Sister Trai Nghiêm in October 2011

Brother Phap Dung and Brother Phap Lai interviewed Sister Trai Nghiem at Plum Village in the spring of 2011.

Question: Were you always a Buddhist, you and your family?

Sister Trai Nghiem: By birth,

An Interview with Sister Trai Nghiem

By Brother Pháp Dung, Brother Phap Lai, Sister Trai Nghiêm in October 2011

Brother Phap Dung and Brother Phap Lai interviewed Sister Trai Nghiem at Plum Village in the spring of 2011.

Question: Were you always a Buddhist, you and your family?

Sister Trai Nghiem: By birth, yes. But not practicing. In Japan, we call it “funeral Buddhism.” Most people go to the temple for the first time when someone in their family dies, for a funeral.

I was twenty-eight when my mom died from cancer. I had contemplated death and impermanence before, but it’s completely different when somebody close to you is actually dying. The comfortable world that I was used to was falling apart. It was really her death that brought me to Buddhism.

Q: As a professional violinist, how has your music motivated you?

TN: I wanted to create something beautiful and to see how far I could reach as a violinist in the world of classical music. I wanted to be part of a world-class orchestra and I enjoyed the years I traveled and performed as a member of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. It was truly a beautiful experience.

Q: Did you have doubts about how far music could take you?

TN: When I was in college, I came across the following quote by Plato: “It is not he who produces a beautiful harmony in playing the lyre or other instruments whom one should consider as the true musician, but he who knows how to make of his own life a perfect harmony in establishing an accord between his feelings, his words, and his acts.” These words shook me violently, as I knew in my heart that I was not the true musician that I wanted to be. Even though I was enjoying a successful career and a lifestyle I had dreamed of, I was feeling stuck. The only way out was to completely let that go. When I decided to ordain as a nun, and was cleaning up my apartment, I found Plato’s quote again. This time his words brought me a smile. I still keep that piece of paper with me.

Q: What brought you to Plum Village?

TN: When I was younger, I saw beauty in fighting and going against the flow. But when my mom died, I ran out of energy to fight, and I decided to just let myself be carried in the flow of life and see what would happen. At that time, Thay’s books came into my life and they brought me a lot of comfort. I came to Plum Village for the first time in the winter of 2007 and I immediately felt at home.

Q: Did it feel like a paradise?

TN: To be honest, I couldn’t stand the practice songs, like “Breathing In, Breathing Out,” at first. And when I heard the monks and nuns chanting, it was so out of tune! But there was something else. There was this sweetness and warmth.

Before Plum Village I went to some zazen meditation sessions and yoga retreats. But it seemed that we were all caught up in ourselves, in our own pursuit of whatever we were trying to attain. And at Plum Village it was just a bunch of people living simply, being kind to each other, just like the way human beings are supposed to be. I fell in love with it.

Q: With the songs, too?

TN: Not immediately... but then I realized that this was my practice and saw that I needed to practice letting go of my judgmental, analytical, and cynical mind in order to just enjoy the present moment. Today I realize that the practice songs are one of the most clever methods of practice in our tradition. The moment I find myself in a foul mood, a song like “Happiness” comes to my rescue. Because we sing the songs every day, they are embedded in our store consciousness and become available whenever we are carried away in forgetfulness. Knowing their powerful “medicinal” effect, now I sing songs wholeheartedly with the gestures and everything.

Q: What attracted you to becoming a nun?

TN: I was always interested in some kind of spiritual life. But I could not imagine letting go of this wonderful life as a professional musician. I also didn’t want to disappoint people around me. I had a consultation with a sister on my first visit to Plum Village and she said, “You don’t need to think about it now, because when the moment comes, you will know.”

Three months later, there was a retreat in Rome, and luckily I happened to be working in Italy so I went. On the last day of the retreat I was taking a train back to my work, and got a phone call from Japan, saying my father was very ill and was hospitalized. So I cancelled my work and went back to Japan to be with my father.

That summer, my father passed away. I had a lot to take care of around his death as well as with my work. I felt like I was running and running and could not stop. I knew that I could not go on like this for too long without damaging myself completely. I decided to be compassionate with myself and signed up for the Winter Retreat. I told myself, I don’t need to do anything, just let myself rest. Every night I’d sit in the Buddha Hall for a long time, alone. I wanted quietness. No music, no talking. After about a month of living with the sisters in New Hamlet, I knew this was it. The question, “Do I want to quit my job and become a nun?” was no longer there because I was already on the path even though my head was not yet shaved.

Q: What happened to your relationship to your music when you became an aspirant?

TN: One night I was sitting and I understood for the first time what it means to have “nowhere to go, nothing to do.” And then I realized, “Oh, I’m actually letting go of all the things that used to mean so much to me.” I had had no desire to listen to music since I arrived at Plum Village, but suddenly I had a desire to listen to a Brahms symphony. In my bed, I turned on the iPod and tears kept flowing. I realized, this is the world I was living in, and I have never appreciated it the way I could have. This incredible world of music had been with me since I was five. And now I was listening to the music and it touched me in a completely different way. I knew that the music was in me, but at the same time I was already standing outside of that world I was so used to. I knew there was no going back. I realized how lucky I had been my whole life to have music to take refuge in and to guide me.

Q: Do you see a similarity between being a musician and a monastic?

TN: Very much so. The Sangha is like an orchestra. Each member has a unique role and is irreplaceable. There is a percussionist who may play only one note in the entire symphony, while the violinists are playing the whole time without any rest. We’d never think of complaining that it’s not fair because that’s what makes the music so beautiful. To live happily in the Sangha, we also have to accept that each person has his or her own role. Some work more hours than others, but that’s just how it is. We suffer when we get caught in the complex of equality. When the orchestra is in harmony, we hear the sound of the orchestra as a whole, as one big instrument. If you heard the individual sound of each violinist in the orchestra, it wouldn’t be pleasant. We melt our individual sounds into the collective sound, so that there is no longer the distinction between “my sound” and “others’ sounds.”

One time, Sir Colin Davis, a wonderful English conductor, said during a rehearsal, when things weren’t quite jelling together: “Whoever tries to prove himself right is a terrorist!” Miraculously, we played in perfect harmony after this proclamation. Each member of an orchestra is an artist in his or her own right, yet when we try to convince others how it should be done, it never works. This teaching can very well be applied to Sangha life. In order not to create suffering for myself or others, I need to monitor my thoughts constantly, to see if I am caught in my own ideas.

If Sangha is an orchestra, Thay is a conductor. A skillful conductor never tries to control the musicians. He just lets the orchestra play. That’s exactly what Thay says to us all the time: “Di choi!” The literal translation is “go play!” It can also be translated as “go hang out and have fun.” Thay, just like a skillful conductor, trusts the Sangha, and based on that trust, he can bring out the best in each member of the Sangha. A layperson asked me once why Thay travels with so many monastics when he goes on a teaching tour. I said, “It doesn’t make sense for a conductor to go on a concert tour without his orchestra. We inter-are.”

When the whole Sangha is sitting together in the morning, it’s like an orchestra tuning up before a concert. I never tried to play the violin without tuning. Why should it be different with my body and mind? If I start out a day by tuning myself with the Sangha, the whole day is so much more harmonious and pleasant.

Q: You’ve lived and worked in many countries, and it seems like you led a very independent lifestyle, choosing your own schedule. The Sangha has a more mannered and restrained lifestyle. How does that feel?

TN: I used to have an idea about what it meant to be a monastic. I told my colleagues that I was quitting this traveling lifestyle and going into a quiet monastery in France, and for the first two years I wouldn’t go anywhere. And suddenly Thay says, okay, you’re going on tour. And I thought, this is not very different from what I was doing before. That’s what makes Thay a Zen master, because as soon as you get caught in your idea of how things should be, he will give you the Zen ax with a smile. I was caught in my idea of what monastic life as a novice was, a quiet life, out in the countryside, tending the vegetable garden.

Actually, the practice doesn’t depend on outer form at all. It’s not what you do but how you do it. If I choose to be fully mindful when traveling and going out on retreats, I can make progress on the path. If there is no mindfulness, it’s a waste of time to be sitting, walking slowly, and studying sutras, even in a monastery. No matter what I do, whether cooking, cleaning, studying, or traveling, I remind myself to be mindful and enjoy doing it.

Q: What’s the best thing about being a novice?

TN: It’s like being a protected baby in a family. There are so many older brothers and sisters who can teach and guide me in different ways. I enjoy having the space to make mistakes. I have the habit energy of wanting to achieve something, so I’m practicing to let go of my idea of what it means to be a “good nun.” There’s a kind of collective idea of what a good monastic is, just as there is a collective agreement of what a good musician is. If I try to become “a good nun,” I will get stuck in the same place where I got stuck as a musician.

Since I was small, everything I did, I did quite well. So I still have the feeling that whatever I do, I should be able to do well. Even though I am aware of this habit energy and am carefully monitoring it by recognizing the motivation for my actions, it’s still there on a deeper level and is the cause of some basic underlying stress.

Q: Is pride an issue for you? Does it manifest sometimes as feeling superior towards others in the community?

TN: It manifests with self-disgust. It’s probably one of the most shameful things to admit. But a superiority complex is nothing more than another face of an inferiority complex. They are like two sides of one coin. Whenever I notice the complex of inferiority manifesting, I tell myself, “You ARE enough.”

I am happy to acknowledge that in the fifteen months since I became a nun, I’ve reduced my level of judgment and criticism towards myself and other people greatly. Having negative thoughts like judgments is a great waste of precious energy. Just as I take care not to waste natural resources like water and food, I also try to conserve my own energy so it can be used for something more beneficial. As a result, I feel much more relaxed than before and many people have shared with me that they notice the difference. Thanks to the Sangha, one thing I have learned so far in my novice life is this: being kind is so much more important than being good at something.

Q: Do you have any aspirations?

TN: To be happy. I didn’t always have a good relationship with my parents, but after they passed away I realized how much unconditional love they gave me. Whatever they did, I feel the only thing they wanted was for me to be happy. But because I was not able to recognize it until they were gone in their physical form, I had this regret; I wanted to make them happier, to do something for them. Now I know the way to pay respect to my parents is to just be happy. I’m practicing with and for my parents.

After their death, I’m so much more in contact with them. This sounds kind of cheesy, but I feel like they’re guiding me in every moment. I really feel their presence a lot more than I used to. If I don’t know what to do, I take refuge in my parents and let them do things. If I listen deeply, they always guide me to the right direction. I really feel that my parents brought me to this point in my life right now. And not only my parents, but all my ancestors—blood, land, and spiritual ancestors. And that includes all the wonderful musicians I have encountered in my life, like Bach and Mozart.