By Trang Nguyễn on

Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh (Thầy) officially gave up his temporary body at 1:30 a.m. on January 22, 2022. Even that moment of farewell becomes sacred—the previous day ending and a new one beginning with much belief and hope! His body has gone through the whole life cycle of birth, old age, illness, and death. The body, made from the earth,

By Trang Nguyễn on

Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh (Thầy) officially gave up his temporary body at 1:30 a.m. on January 22, 2022. Even that moment of farewell becomes sacred—the previous day ending and a new one beginning with much belief and hope! His body has gone through the whole life cycle of birth, old age, illness, and death. The body, made from the earth, water, wind, and fire, will transform into dust. However, the image of Thầy—a Buddhist monk, philosophical researcher, writer, poet, and peace activist from Vietnam—will live forever in the hearts of humankind. When people who love him are peaceful and quiet, they see him right here, right now, in their mind, in every drop of dew on the leaves, and in the clouds floating in the sky.

When I was a teenager, I did not care about being beautiful or cute to attract boys; I even “discriminated” against them and was very cold to them. My friends could not understand my lifestyle and thought of me as odd. I preferred to spend time in silence and think about the sufferings of life. At the age of twelve, I even wanted to be ordained in a Buddhist temple. One of the remarkable figures who greatly influenced me at that young age was Thầy.

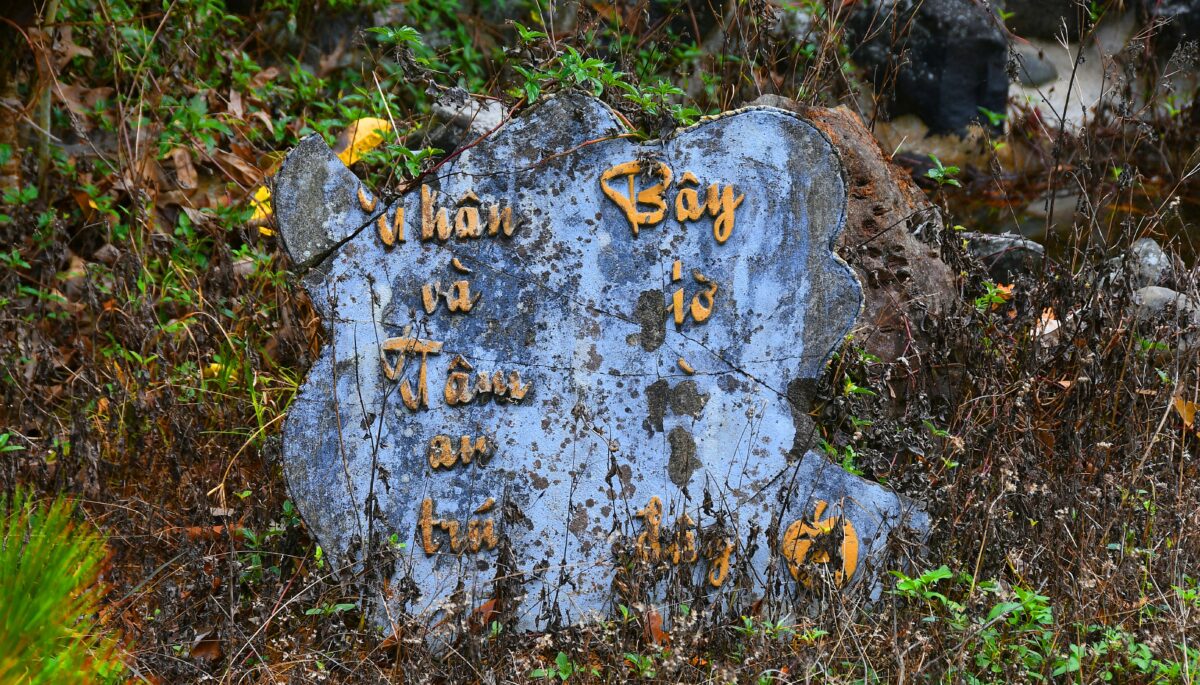

I read a few complicated Buddhist philosophical books when my mind was still young and naive. Although I was passionate about studying Buddhism, understanding those books was virtually impossible. But when I read Thầy’s memoir, Fragrant Palm Leaves (Nẻo về của ý), it gave me a feeling of relief, because the storytelling was easy to follow and it made me feel connected with Thầy’s personal memories of his experiences. In particular, I was inspired by his story about Phương Bối temple located in Bảo Lộc. Because I was born in a highland village and raised in Bảo Lộc, I immediately could connect with the vivid descriptions of the mountainous scenery, dense forests, colorful flowers, and chirping birds. Although I had never met Thầy in person, I have always felt an invisible connection with him—a feeling of closeness that is indescribable!

Then, as if it were a result of previous karmas, I soon became one of the first youths in the area to attend a retreat organized by the Plum Village Community at Bát Nhã Monastery located in Bảo Lộc. Active and noisy teenagers who liked to run and yell loudly now had to eat and walk in silence and with a mindfulness to which they were clearly not accustomed. I still remember a group of boys who, while having lunch, nudged each other with their elbows, then covered their mouths with their hands to keep from bursting out in laughter.

The retreat had a profound psychological impact on me, an introverted teenager. I was comfortable living in silence with other participants around me, mindfully eating with a group gathered under a pine tree, and singing poetic meditation songs. Additionally, I was impressed by the gentle, youthful, and almost ethereal voice of Sister True Emptiness (Chân Không) during the noon breaks. The nun would sing for a few minutes, and then I would hear someone snoring next to me. Later, as an adult social worker in psychotherapeutic camps for HIV-infected children or other community development programs, I loved to teach the Vietnamese version of the song “Breathing In, Breathing Out,” with its accompanying dance, which was my favorite at the retreat:

Breathing in, breathing out, as a fresh flower, as a steady mountain, as the still shining water, as vast space.

During the last year of high school, while my classmates were stressed and studying hard to prepare for two crucial examinations needed to graduate and enroll in higher education, I took a day off from school to work as a volunteer during a big, special Buddhist event in my town. My task was to support the traffic police standing across a road to prevent vehicles from entering a particular street that was set up for the delegation of Plum Village members to walk through. Hundreds of monastics in simple brown robes, carrying Vietnamese conical hats (nón lá), followed each other in two neat lines and slowly walked close to the edge of the road.

Buddhist laypeople joyfully prepared vegetarian food to offer to monastics. A few monks and nuns smiled at me and put some rice cakes and oranges into my hands when they saw our group of volunteers covered in sweat, our faces red in the scorching sun. I kept looking at them happily: how beautiful and “glowing” they were! The monastics did not need hair, and the nuns had no makeup or fashionable outfits, but their elegant faces and features radiated calm and peace. It reminded me of the Vietnamese proverb: “The mind creates the outlook” (tâm sinh tướng). Since then, the image of the Plum Village nuns has become a model for me to learn from: I should live my life by building beauty from the inside out.

Everyone passing through the street stopped and watched the event with curiosity. Someone excitedly yelled: “Hey! There are some foreign monks and nuns there!” Seeing tall white European and American monastics in the congregation surprised many local people; they were goggle-eyed and could not believe what they were seeing. Later on, when I listened to Thầy’s audiobook Old Path White Clouds (Đường Xưa Mây Trắng), the description of the Buddha and his disciples walking into a village for alms reminded me of the scene of the Plum Village Sangha in my hometown. The scene was simple but majestic beyond words.

Most of the meditation retreats conducted in Bát Nhã (Prajñā) Monastery, Bảo Lộc, were coordinated by Thầy’s disciples. It was infrequent for Thầy to give lectures directly. Still, every time he visited Vietnam, Buddhist communities were delighted and thrilled to participate in many events and ceremonies led by him. Once, I was fortunate to join thousands of Buddhists to listen to a Dharma talk given by Thầy. I looked thoughtfully for a long time at Thầy and saw that he was very different from many of the monks I knew locally. Thầy was contemplative, gentle, smiling, and looked very serene. Maybe because of technical problems with the microphone, his voice seemed not clear enough to me. Unfortunately, at that time, with the agitated and busy mind of a seventeen-year-old girl, I did not concentrate on listening and understanding his teachings well. I didn't even realize how precious it was to sit there and listen to Thầy’s talk!

The meditation courses organized in Bát Nhã were increasingly successful and attracted many Buddhists and even non-Buddhists from all over Vietnam, especially young people—up to thousands at a time. Then something unexpected occurred, about which I do not know whether to laugh or cry. Quite a lot of young meditation practitioners who had attended the retreats did not want to leave. Instead, they wanted to stay and wished to be ordained into the Plum Village tradition. Their parents had to take buses to the monastery to ask or even beg their children to return home. I once heard that one of my childhood friends became a nun there, but I do not know where she is now and what happened to her. Another friend became a lay trainee in the monastery for a year. I myself had been greatly inspired during and after the retreat in Plum Village, especially by Thầy, and also wished to become a nun. However, I was unable to do so at the time.

A few years later, every time I returned from Sài Gòn to visit Bảo Lộc, I would stop by Bát Nhã. Occasionally, I would have a chance to talk with some nuns. One nun told me about her suffering and brokenhearted life experience, and how she transformed her mind positively after several years of “bathing” in mindfulness with the Plum Village Sangha. I still vividly remember the words she shared in a pine forest: “Sister! This is what I think: we are immature; our mind is like a young pine tree that is not yet sturdy. Therefore, it is easily blown by the stormy wind, its branches are broken, and its trunk is uprooted. So, living here, not being allowed to use phones or computers for entertainment, not owning anything, and spending most of my time practicing mindfulness to realize the nature of interbeing every day is essential! As a result of this steady training we grow strong. One day, when the pine tree matures and becomes much sturdier and more stable, it will be ready to face the storms of life, which are full of troubles and temptations!”

Unfortunately, the Plum Village Sangha had to leave Bát Nhã Monastery in 2009 because of unexpected vicissitudes, which made many people shocked and sad. Thầy’s dream of building a Dharma institution in Bảo Lộc called Phương Bối, as in the old days, was unfulfilled.

However, the good news is that many practitioners from Bát Nhã, as Dharma seeds, have spread the Order of Interbeing tradition to all parts of the country. They have established many Buddhist communities that follow Thầy’s mindfulness practices and conduct retreats with no presence of any monastics. I once attended such a one-day meditation retreat in Sài Gòn. A small group of about ten people gathered on a Sunday. We sat quietly and meditated for a while in several sessions. Then, we had a tea meditation that consisted of snacking, drinking tea, sharing our inner thoughts, and singing Plum Village meditation songs. Our lunch followed the same buffet-style model as during the retreat in Bát Nhã: we took as much food as we could eat, gathered in a circle, ate in silence, and concentrated on enjoying our breathing. After that, whoever finished their lunch got up and washed their used dishes as a meditation.

Being occupied with community development projects almost every weekend, I could not join such retreats anymore, but my heart was gleeful. Closing my eyes, I still can see those Buddhists, the pine trees at Bát Nhã, the peaceful smiles on the meditators’ faces, Thầy’s serene demeanor, and the mountainous beauty of Bảo Lộc—my highland homeland. I also vividly remember the moments when the bell rang: everyone in the monastery had to stop what they were doing immediately, to stay quiet and breathe for a while. The bell reminded the body and mind to become one. It was simple but surprisingly effective!

Thích Nhất Hạnh lived through turbulent times during the war in Vietnam. But the war made that great man only more determined, more compassionate, and stronger. The legacy he left will live on forever and help humanity. In the same way, the image of Thầy is still with us, in every breath, every peaceful step, every happy smile, in the wind and clouds. Personally, when I think about Phương Bối, Bảo Lộc, the pine forest in Bát Nhã Monastery, or my Vietnamese hometown, I see Thầy and the Plum Village contemplatives in simple brown robes with their peaceful vibe. Remembering the Plum Village teachings, I understand that the only true happiness is right here and now. The joys or sorrows of the outside come and go. If we cling to them, we lose precious time in our lives due to our lack of mindfulness.

I’m not a mindful person yet, but I know I will not give up trying to become one.

Written for Thầy Nhất Hạnh on January 25, 2022.