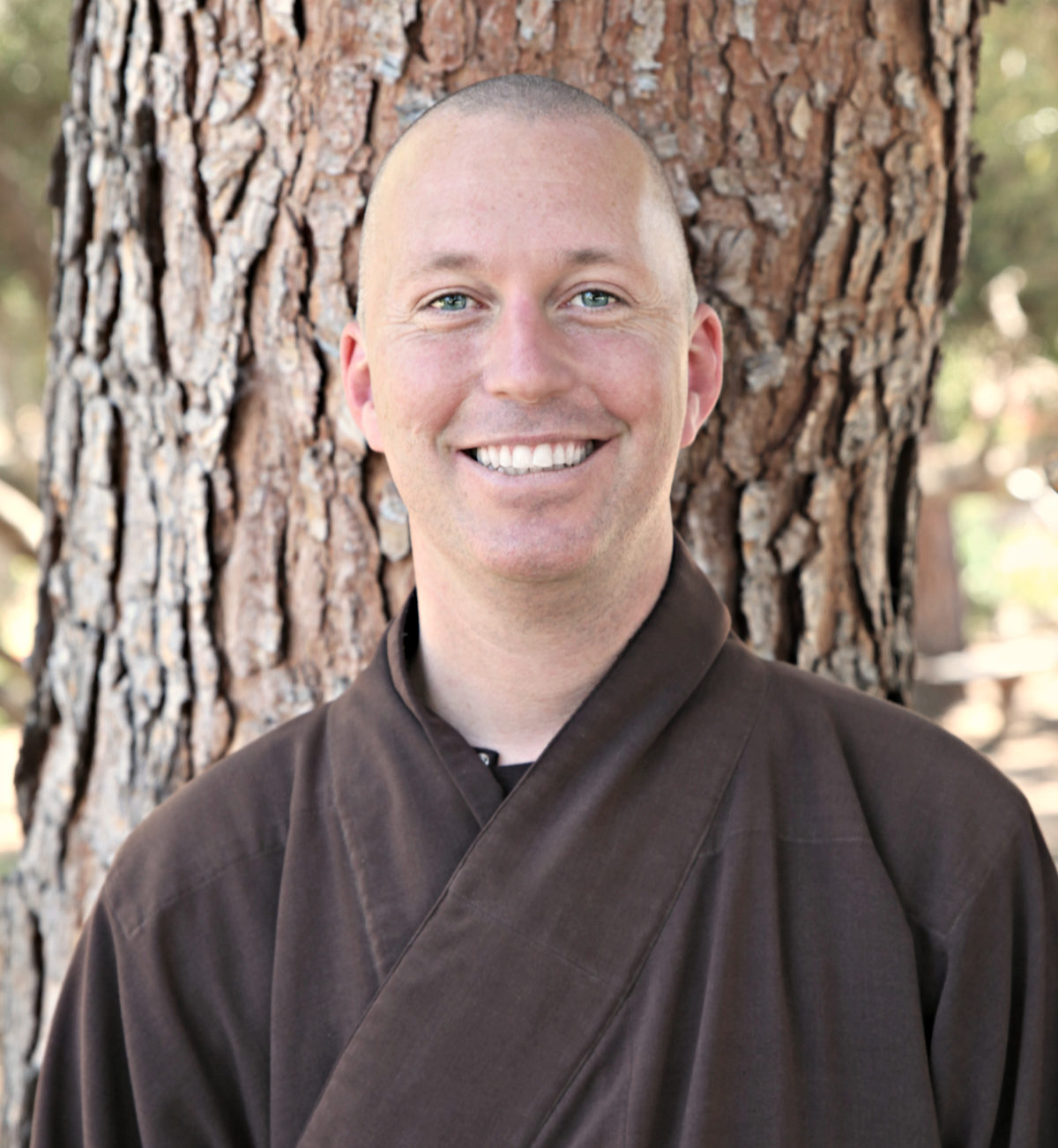

By Brother Chan Phap Hai

In this excerpt of The Eight Realizations of Great Beings: Buddhist Wisdom for Waking Up to Who You Are, Brother Phap Hai shares the story of his journey to Plum Village and some of the teachers he met on the way.

In the old European wisdom traditions, a crossroad is seen as a sacred place,

By Brother Chan Phap Hai

In this excerpt of The Eight Realizations of Great Beings: Buddhist Wisdom for Waking Up to Who You Are, Brother Phap Hai shares the story of his journey to Plum Village and some of the teachers he met on the way.

In the old European wisdom traditions, a crossroad is seen as a sacred place, where you will meet a wise teacher who invites you to embrace deeply that moment “in between” stages of life, when all things are possible. When I look back and see the teachers I met at various crossroads in my life, I can only feel a deep sense of humility and gratitude.

During my final two years as an apprentice chef, I spent a lot of my free time at a local Chinese Buddhist temple. One day while I was at the temple, I met a lovely Burmese couple who were disciples of an Australian-born monk of the Theravada Forest tradition who was living nearby. They asked me whether I would like to visit him. I was intrigued to have a chance to hear teachings in English, as well as to receive more focused meditation instruction. So, on my next day off, I accompanied my new friends to visit the monk in his simple forest hut, overlooking the Glasshouse Mountains in Australia.

I was blown away by the simple, direct, practical, and structured teaching that he offered. That meeting changed my life, and I began spending most of my days off in the forest, practicing intensive meditation. At weekends I would go and stay with him, and we would wake up at 3 a.m., alternating between sitting meditation and walking meditation the whole day. I loved every second of it.

As I was coming to a completion of my time as an apprentice, I began reflecting on my way forward. Looking objectively at my life, it became clear to me that the thing that I enjoyed doing the most was meditation, and I was increasingly interested in monastic life. That grounding in meditative experience with this teacher provided a firm foundation for my spiritual practice.

When the monk told me that he was about to return to Sri Lanka, I made the decision to follow him there and explore ordination as a monk myself. Arriving in Sri Lanka, we traveled to a hermitage near the town of Bandarawela. My room in the hermitage overlooked the tea plantations. In many ways, my time there was idyllic because at last I was living in a place where I could immerse myself in meditation. However wonderful that was, there also seemed to be a disconnect between my simple, peaceful existence and the difficult situation of the country and its people, who were at the time in the midst of a violent civil war. Whenever I would ask my teacher about the political and social situation, he would reply that the conflict was the work of unskillful minds and that, as meditators, we should not get involved with or even think too much about the world outside. I understood his thinking, but it felt to me as if something was missing.

After a couple of months, we went to visit another forest hermitage, and I had a chance to have tea with some of the monks who were in residence there. In the course of our conversation, one of the monks shared, “I never travel to town if I can avoid it. The noise, and the way people’s minds work disturbs my meditation.” In a way, I understood and even tended to agree with him. But looking deeply, I felt that if I were not attentive, this attitude could easily become a form of avoidance and any peace or insight that I might develop would be dependent on outer conditions. I wanted to practice in such a way that everywhere was my place of practice, and that I didn’t need a special environment.

I kept these thoughts secretly in my heart. About a week later, I was cleaning the library in the hermitage and noticed the book The Miracle of Being Awake: A Manual on Meditation for Activists by Thich Nhat Hanh. It was an earlier version of The Miracle of Mindfulness, one of Thay’s most popular books of all time. I devoured that book, feeling as if the author were speaking directly to me when he spoke of mindfulness in daily life. A great change came over my practice as elements of ease, relaxation, and delight began to manifest.

Not too long after my encounter with Thay’s book, the war in Sri Lanka escalated and it was no longer safe for me to remain there. After some consideration, I felt that it was a sign for me to return to Australia, that I had learned what I needed to learn and that something else was waiting. Taking leave of my teacher, I returned to Australia. On arriving back, I was faced with a choice: to return to my job as a chef, or continue to follow my spiritual path. Against the advice of every single person in my family and group of friends, I decided to continue along the spiritual path.

I sat down with the phone book and looked up all the listings in Brisbane for Buddhist temples.

This was long before the Internet, and Google would have made it much easier! But, being young and inspired, I set out undaunted on my search. One of the names of the temples caught my eye: Chua Phat Da. I caught the train, got off at the station nearest to the address, and began walking. It was about three miles on foot. After a long, hot walk, I finally arrived at Chua Phat Da, which at the time consisted of a converted old army barracks and a simple wooden house behind.

The door of the main hall was open, so I walked in. The atmosphere was calm and quiet. Not seeing anyone, I sat in meditation silently. After some time, I heard footsteps and opened my eyes. An old woman in nun’s clothing had appeared. She looked at me quizzically, and I tried to tell her that I was interested in monastic life. She spoke no English, and I spoke no Vietnamese. But after a while, she made a phone call; an older gentleman, a Mr. Le who did speak English, appeared at the temple. We sat down, and I explained everything to him. He shared with me that one of the nuns at the temple, Sister Tu Ngoc, spoke English and that he would take me to see her. Off we went to meet Sister Tu Ngoc. Sister Tu Ngoc is originally from Hue, and her family home is very close to Tu Hieu, our root temple in Vietnam. She had known Thay and Sister Chan Khong for a long time. During our conversation, Sister

Tu Ngoc gave me Thay’s book Cultivating the Mind of Love and asked me to come back to the temple on Sunday to the service.

Chua Phat Da is a Pure Land Buddhist temple; I remember the Buddha hall being full of people, all chanting wholeheartedly. After the service, Sister Tu Ngoc introduced me to the congregation, and I kept coming to the Sunday services for a few weeks. One Sunday, Sister Tu Ngoc approached me and said, “You are a good boy, why don’t you stay in the temple?” I moved into the house at the back of the temple and worked around the temple cutting grass, cleaning, and driving the temple bus to pick up the older parishioners on Sundays—even on a couple of occasions inviting the bell for the Sunday chanting. The community also provided me with Vietnamese language lessons, which I was spectacularly bad at in the beginning!

There was also a small group of practitioners who had formed a local Sangha in the Plum Village tradition, and I became part of that Vietnamese Sangha. By the way, that local Sangha has given rise to three monastics in Plum Village: Sister Le Nghiem, Sister Mai Thon, and me. As the months passed, two schools of thought about my path developed in Chua Phat Da: one was to send me to Canada to ordain in the traditional Vietnamese lineage, and the other was to send me to Plum Village.

As you can probably guess, the Plum Village cohort won the debate, and they began raising money to send me to Plum Village to ordain. Stepping onto the land of Upper Hamlet, the very first person I met was Sister Chan Khong, who greeted me warmly on that cold November day. I fell in love with the simple, joyful, and wholehearted way of life in Plum Village immediately. At the time, the monastic community was very small, not like today. There were just a few brothers, fewer than twenty. As I continued to practice there, each and every day, I felt more strongly that I had come home and that this was my family and my community.

The Eight Realizations of Great Beings: Buddhist Wisdom for Waking Up to Who You Are will be available at parallax.org and wherever books are sold in July 2021.