An Open Heart Is Called for Now

By Marisela B. Gomez MD, Valerie Brown in October 2015

The Dharma teaches us that the daily steps of life are where we awaken. We learn that it is possible to awaken to the reality of the suffering of this existence, and to the path that provides us a choice,

An Open Heart Is Called for Now

By Marisela B. Gomez MD, Valerie Brown in October 2015

The Dharma teaches us that the daily steps of life are where we awaken. We learn that it is possible to awaken to the reality of the suffering of this existence, and to the path that provides us a choice, a road toward liberation, understanding, and love.

THE PATH OF RACIAL AND SOCIAL INEQUITY

Clementa Carlos Pinckney was called to walk this path at age thirteen. Walking a dusty road in rural South Carolina as a young African American adolescent, he suddenly stopped when he heard a voice that said, “Preach.” Determined to serve God and his community, he was ordained at eighteen. Pinckney had been born into a family steeped in church leadership and civil rights activism. Both a maternal great-grandfather, Lorenzo Stevenson, and a great-uncle, Levern Stevenson, were African Methodist Episcopal pastors who fought segregation in South Carolina through legal challenges and boycotts. After Levern confronted a white school bus driver who refused to drop his children near their home, marauders torched their house as the family slept inside. They grabbed their shoes and escaped.

Young Pinckney presided over student government in high school and college; and at twenty-three, he became the youngest black member of the South Carolina state legislature. After serving two terms in the South Carolina House of Representatives, he was elected to the state senate. He was known within his community for his empathy even for those he disagreed with, and for his disarming humility, although he also firmly presented his own views.

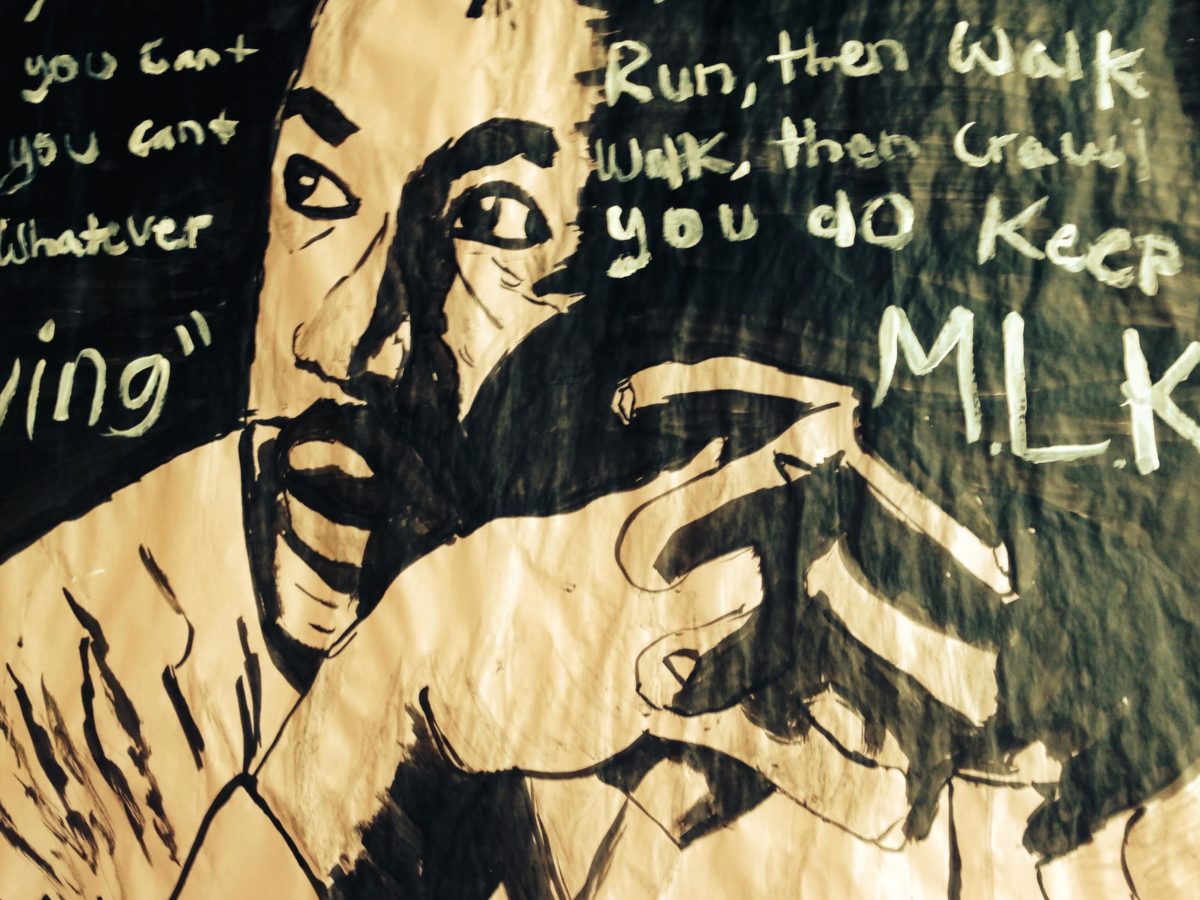

Pinckney and eight others were brutally massacred by a white twenty-one-year-old gunman during Bible study in the basement of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015. Built by African Americans seeking liberty, historically the church was a place where African Americans gathered in defiance of unjust laws that banned their church gatherings. It is the place where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached from the sanctuary of the pulpit.

In eulogizing Pinckney and the eight other slain victims, President Barack Obama called on Americans to confront the “uncomfortable truths” of the racial prejudices that still infect American society. He said, “an open heart … is what’s called upon right now.” 1 Less than one week earlier, he had asserted, “It is incontrovertible that race relations have improved significantly during my lifetime and yours, and that opportunities have opened up, and that attitudes have changed. That is a fact. What is also true is that the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination, in almost every institution of our lives, casts a long shadow. And that’s still part of our DNA that’s passed on. We’re not cured of it. Racism—we are not cured of it.” 2

This “uncomfortable truth” preceded the deaths of the nine innocent victims in Charleston. Racial violence, perpetuated through systems and individuals, is a horrific part of the American landscape, evidenced by the nearly daily news stories of pervasive violence against African Americans and people of color within the United States. Tragically, these names, places, and people are too familiar: Ferguson; Baltimore; McKinney, Texas; Rekia Boyd; Trayvon Martin; and countless others. In 2015, as of June, 490 people have been killed in the United States by police, according to a Reuters report. African Americans were disproportionately represented in these killings, making up thirty percent even though they represent only twelve percent of the US population.

Legal scholar Michelle Alexander has characterized the mass incarceration of black people, linked with the war on drugs over the past three decades, as the “new Jim Crow.” 3 The prison population has, according to Alexander, increased from 300,000 to 2.3 million in the past thirty-five years, with blacks making up almost half that number. But the systematic ways in which racism manifests in the US go beyond the criminal justice system. Studies continue to show gaps between white communities and communities of color in income, wealth, health, employment, and educational attainment. Our communities continue to be segregated by race and income; historically, those with African Americans and people of color as the majority have disproportionately lacked resources. Today in the United States, we are blooming the weeds of chaos, violence, and racial and class inequity from seeds planted centuries ago. All this has sparked massive waves of uprising across the country. It is time for change.

“IN A RACIALLY UNJUST WORLD, WHAT GOOD IS MINDFULNESS?"

We are consistently reminded of the ways that race intersects with judgment in our daily lives, leading to false assumptions, violence, and frequently death. As mindfulness practitioners, we are called to reflect on these “uncomfortable truths” through the lens of the Dharma.

In January, at a benefit for the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland, California, Angela Y. Davis, an African American political activist, scholar, and author, posed this profoundly important question to Jon Kabat-Zinn, European American Professor of Medicine emeritus and creator of the Stress Reduction Clinic and the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Davis asked, “In a racially unjust world, what good is mindfulness?”4 Kabat-Zinn answered that mindfulness practice can gradually uproot the greed, hatred, and delusion that lead to suffering. Later in the evening, Davis responded to the question as well, saying mindfulness may be a radical force to help social movements that challenge institutionalized oppression.

Mindfulness, in cultivating awareness, compassion, understanding, and insight, is a path of practice that can decrease bias, which is the result of ignorance and wrong perceptions. The path of mindfulness leads us toward understanding, love, forgiveness, and peace, in the daily ways we interact with our inner world and with the world around us.

In May, Buddhist teachers from around the world met in the United States to discuss ongoing violence against people of color. They said, “Right now, we believe there is an immediacy and urgency in focusing our attentions and efforts on the pervasive and ongoing violence done to people of color in our country.”5 This was followed in June with Buddhist teachers’ call to action and request for support in an open letter addressing “racial justice as an expression of your commitment to actively work towards ending racism.”

The time is now to use the mud of racial injustice to transform and heal its effect on all people: people of color and whites. Racial injustice hurts the oppressed and the oppressor because we are not separated from each other. If we go as a river, our collective power can become a path of understanding that the separation of “us” and “them” breeds racism and justifies differential and inequitable treatment. We can understand the truth that white privilege exists along with non-white under-privilege, and that the accumulation of such privilege is part of all forms of racial inequity.

The path of mindfulness offers a way to nurture our inner joy and peace, preparing us to meet these “uncomfortable truths” within and around us with patience, forgiveness, and spaciousness. Right view grounds us in the clarity of non-discrimination, non-harming, and non-self, and provides the framework for right words, actions, mindfulness, and insight. With patience, peace, and compassion, the truth of the causes and consequences of racial injustice can be looked into, understood, and transformed.

On an individual level, the pervasive role of implicit bias, unconsciously perpetuated through lack of awareness, can be recognized in the ways it may differ from our explicit beliefs and behaviors. 6 We are unconscious to our implicit biases, how they operate, and how they affect us and those around us. Our failure to become aware of these implicit biases can strengthen the deep roots and the legacy of racial inequity and white privilege. Racially motivated micro-aggressions and micro-inequities—the subtle, covert, and frequently daily forms of discrimination—are often outside of the awareness of both the perpetrator and the one who is hurt, yet they are commonplace and continue a cycle of harm. When we have the courage to question and transform our implicit biases in regard to racial discrimination, unwise judgment, and separation, thereby changing potential causes of pain and suffering, we may reach right view.

Looking deeply into the ways our thoughts, words, and actions have been shaped by our social environment and culture, and how they explicitly lead to racial discrimination, is also key in shining light on ourselves in relation to others, whether they are racially similar or different from us. The path of mindfulness—breathing, walking, eating, smiling, stopping, sitting in awareness, remembering our path of love and understanding—can provide the spaciousness to notice and transform us in the direction of non-discrimination and understanding, and prevent harmful habit energies from manifesting.

Moving through life with a view that one is “color blind” denies the reality of implicit bias and micro-aggressions. We are reminded of the story of a blind man carrying a lantern to help others see; however, when the light was extinguished he was unaware of it because of his blindness. Like this man, we are often blind to our own lack of consciousness, or our unlit lantern. Being blind to our unconsciousness leads to implicit biases and micro-inequities, and it can cause deep suffering until we cultivate the light inside ourselves to see clearly. Mindfulness can illuminate our path of clarity and spaciousness with calm and ease, revealing our unconscious biases and preventing painful outcomes.

OUR COLLECTIVE PATH OF HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

The Dharma teaches us that there is a path of understanding and love. Our Sanghas teach us that in supportive community, we can cultivate the spaciousness to look deeply into our unconsciousness, engaging with “uncomfortable truths” without shame and blame. Our deep looking brings understanding of how these truths can become the light of awareness that prevents us, as individuals and as communities, from perpetuating racial and social separation and suffering. Our own individual understanding is key to transforming systems of racial and social oppression.

Our collective blindness, as individuals and as communities, can be transformed to address the systematic ways white privilege has disproportionately benefitted a particular race and class of people while disadvantaging people of color. Such systems have created communities of separation and abandonment, which are vulnerable not only to the structural violence of criminal justice systems but also the institutional violence that causes disparities in education, health, housing, recreation, employment, transportation, and social services. The recent acts of violence against blacks in particular and people of color in general within the United States urge us to unite our collective energies to radically transform and heal, and embrace the right view of non-separation and non-self.

A CALL TO ACTION

It is time to change—to transform in the spirit of love, in the spirit of openness, and in the spirit of peace. We invite Sanghas to actively engage in a process of understanding and building beloved community by:

• Creating safe and loving spaces for white allies of people of color to engage in looking deeply, understanding, and healing from implicit bias and other forms of discrimination;

• Creating safe and loving spaces for white allies to understand the systemic legacy of racial inequity and to provide opportunities for learning and practice;

• Creating safe and loving spaces for people of color to heal from the trauma of racial injustice and inequity;

• Creating safe and loving spaces for people of color and white allies to come together to look deeply and engage in healing together;

• Looking deeply at and addressing the under-representation of people of color and low-income people in our individual Sanghas and the collective Sangha.

The congregants of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church were practicing right view when they opened their hearts and their church to a young white stranger in their midst. This young man did not understand how his years of being exposed to individuals and systems that planted seeds of racial separation, inferiority, and superiority had implicitly and explicitly trained him to hate and demonize all black people. Still, after the horrific event, surviving congregants who witnessed and felt his ignorance and rage maintained an open heart of understanding and love. We are invited to attend to our house of understanding and love, to intentionally engage in building beloved community.