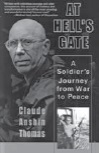

I was deeply touched recently by a book called At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey from War to Peace. The author, Claude Anshin Thomas, describes in detail the suffering he has experienced as a Vietnam veteran [see below]. The description of his suffering made me look more deeply into the experiences of a soldier. I tried to imagine how it would feel to be trained as a killer at the age of eighteen.

I was deeply touched recently by a book called At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey from War to Peace. The author, Claude Anshin Thomas, describes in detail the suffering he has experienced as a Vietnam veteran [see below]. The description of his suffering made me look more deeply into the experiences of a soldier. I tried to imagine how it would feel to be trained as a killer at the age of eighteen. How it would feel to kill another human being. How it would feel to watch my friends die in front of me, or to watch children die as a result of the military action in which I was involved. How it would feel to live in fear of violent death on a day-to-day basis.

Looking deeply at these things helped me to understand the suffering on a different level. I realized, for example, that I could not even begin to think of how I would reconcile the thoughts and emotions around killing another human being, let alone many human beings. I know that labeling the people I killed as “enemy” would not bring me comfort in the long run. I know the energy of those actions would continue with me in some form as long as I lived.

Anshin Thomas also offers his opinion that the United States, as a people, never really took responsibility for the Vietnam War. Most people viewed the war as distant and unconnected to their day-to-day lives. They did not recognize that it was their lifestyles that supported the institutions of war. And, for the most part, they did not offer support for the veterans of the war, or for the victims of the war in Vietnam.

All of this got me to thinking about the war in Iraq, and my connection to that war. I realize that I have not really taken responsibility for my connection to that war. I follow the news about Iraq, and frown at it. I think from time to time about the tragedy of the war, and how I disagree with the U.S. government’s position on the war.

The Light at the Tip of the Candle

By Claude Anshin Thomas

Claude Anshin Thomas came home from the war in Vietnam in 1967. In the years following his military service, his life spiraled downward into post-traumatic stress, drug and alcohol addiction, and homelessness, but his life turned around when he discovered Buddhism. Zen, he found, offered him a path toward healing, a practical way to cope with his suffering rather than run from it. The following took place in 1990, when Thomas attended a meditation retreat for Vietnam veterans led by Thich Nhat Hanh.

I drove to the retreat on my motorcycle. At that time I was riding a black Harley Davidson. I was dressed in a typical fashion for me: black leather jacket, black boots, black helmet, gold mirror glasses, and a red bandanna tied around my neck. My style of dress was not exactly warm and welcoming. The way I presented myself was intended to keep people away, because I was scared, really scared.

I arrived at the retreat early so I could check the place out. Before I could think about anything, I walked the perimeter of the whole place: Where are the boundaries? Where are the dangerous places where I’m vulnerable to attack? Coming here thrust me into the unknown, and for me the unknown meant war. And to be with so many people I didn’t know was terrifying to me, and the feeling of terror also meant war.

After my recon I went down to the registration desk and asked where the camping area was, because I didn’t want to camp where anyone else was camping. I was much too frightened to be near so many strangers. This time each day, sunset, was filled with fear — fear of ambush, fear of attack, fear of war exploding at any moment. Rationally I knew that these things wouldn’t happen, but these fears, like the reality of war, are not rational.

I put my tent in the woods, away from everybody else, and I sat there asking myself, “What am I doing here? Why am I at a Buddhist retreat with a Vietnamese monk? I have to be out of my mind, absolutely crazy.”

The first night of the retreat, Thich Nhat Hanh talked to us. The moment he walked into the room and I looked into his face, I began to cry. I realized for the first time that I didn’t know the Vietnamese in any other way than as my enemy, and this man wasn’t my enemy. It wasn’t a conscious thought; it was an awareness happening from somewhere deep inside me.

As I sat there looking at this Vietnamese man, memories of the war started flooding over me. Things that I hadn’t remembered before, events I had totally forgotten. One of the memories that came back that evening helped me to understand why I had not been able to tolerate the crying of my baby son years earlier.

At some point, maybe six months into my service in Vietnam, we landed outside a village and shut down the engines of our helicopters. Often when we set down near a village the children would rush up and flock around the helicopter, begging for food, trying to sell us bananas or pineapples or Coca-Cola, or attempting to prostitute their mothers or sisters. On this particular day there was a large group of children, maybe 25. They were mostly gathered around the helicopter.

As the number of children grew, the situation became less and less safe because often the Vietcong would use children as weapons against us. So someone chased them off by firing a burst from an M60 machine gun over their heads. As they ran away, a baby was left lying on the ground, crying, maybe two feet from the helicopter in the middle of the group. I started to approach the baby along with three or four other soldiers. That is what my nonwar conditioning told me to do. But in this instance, for some reason, something felt wrong to me. And just as the thought began to rise in my head to yell at the others to stop, just before that thought could be passed by synapse to speech, one of them reached out and picked up the baby, and it blew up. Perhaps the baby had been a booby-trap, a bomb. Perhaps there had been a grenade attack or a mortar attack at just this moment. Whatever the cause, there was an explosion that killed three soldiers and knocked me down, covering me with blood and body parts.

This incident had been so overwhelming that my conscious mind could not hold it. And so this memory had remained inaccessible to me until that evening in 1990 .…

At the retreat, Thich Nhat Hanh said to us, “You veterans are the light at the tip of the candle. You burn hot and bright. You understand deeply the nature of suffering.” He told us that the only way to heal, to transform suffering, is to stand face-to-face with suffering, to realize the intimate details of suffering and how our life in the present is affected by it. He encouraged us to talk about our experiences and told us that we deserved to be listened to, deserved to be understood. He said we represented a powerful force for healing in the world.

He also told us that the nonveterans were more responsible for the war than the veterans.* That because of the interconnectedness of all things, there is no escape from responsibility. That those who think they aren’t responsible are the most responsible. The very lifestyle of the nonveterans supports the institutions of war. The nonveterans, he said, needed to sit down with the veterans and listen, really listen to our experience. They needed to embrace whatever feelings arose in them when engaging with us — not to hide from their experience in our presence, not to try to control it, but just to be present with us.

I spent six days at the retreat. Being with the Vietnamese people gave me the opportunity to step into the emotional chaos that was my experience of Vietnam. And I came to realize that this experience was — and continues to be — a very useful and powerful gift. Without specific awareness of the intimate nature of our suffering, whatever that suffering may be, healing and transformation simply are not possible and we will continue to re-create that suffering and infect others with it.

Toward the end of the retreat I went to Sister Chan Khong to apologize, to try to make amends in some way for all the destruction, the killing I’d taken part in. I didn’t know how to apologize directly; perhaps I didn’t have the courage. All I could manage to say was: “I want to go to Vietnam.” During the retreat they had said, if we who had fought wanted to go to Vietnam to help rebuild the country, they would help arrange it. And so I asked to go to Vietnam; it was all I could say through my tears.

* When Thay gives teachings he does not normally say that nonveterans are more responsible than veterans for the war, but nonveterans are just as responsible as veterans. — Sister Annabel

From At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey from War to Peace, by Claude Anshin Thomas, © 2004, 2006 by Claude A. Thomas. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications Inc., Boston, MA. www.shambhala.com.

Claude Anshin Thomas is a monk in the Soto Zen tradition and the founder of the Zaltho Foundation, a nonprofit organization that promotes peace and nonviolence.