By Brother Phap Co

Dear Thay, dear Sangha,

This morning, I was doing walking meditation with the Sangha. I breathed in and out with every two steps, and after a while, I saw that I was becoming calm. I was able to direct my calm mind to the wondrous surroundings, the green trees, warm sun, flowers, and grasses of Deer Park Monastery. I felt light and at peace.

By Brother Phap Co

Dear Thay, dear Sangha,

This morning, I was doing walking meditation with the Sangha. I breathed in and out with every two steps, and after a while, I saw that I was becoming calm. I was able to direct my calm mind to the wondrous surroundings, the green trees, warm sun, flowers, and grasses of Deer Park Monastery. I felt light and at peace. I continued to bring my peaceful mind into contact with my brothers and sisters and with nature. Gradually I saw I was a part of nature, so no effort was needed to enjoy it, because nature seemed to have permeated me and flowed inside of me. I realized my past is behind me and my future is in front, and if it is beautiful and clear in front of me, then the past behind me is also beautiful and clear. If we live beautifully and mindfully in the present and in the future, then our past will also be beautiful, with wonderful memories.

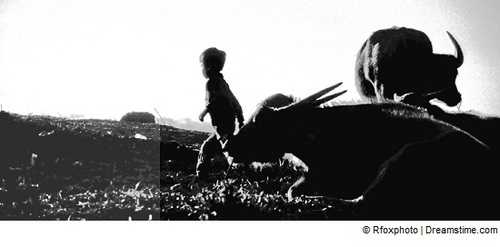

I would like to share my memories about taking care of buffaloes. I grew up in the countryside in Vietnam. My father was a farmer with thirteen children and over thirty water buffaloes. I was the herder in charge of the buffaloes. In the morning, I let the buffaloes out into the fields for grazing, making sure they did not feed on rice plants and other crops. This kind of attention required my constant presence, leaving little time for schoolwork. That’s why by the age of thirteen, I was only in the third grade. In our society at the time, the uneducated and illiterate were often called “buffalo herders.”

When herding buffaloes, one has to know how to keep buffaloes of different characters together. Some buffaloes, once out in the field, will look for rice, sweet potatoes, or other crops to eat rather than staying with the herd. Some buffaloes like to walk by themselves. Some refuse to be led to the field. The first duty of the herder is to collect the herd using three tools: a wooden rod, a long piece of rope, and the best-behaved buffalo, called the “herd gatherer.” This buffalo must be the fastest, strongest, and best trained of the herd. If a buffalo decides to leave the herd, the herder must promptly dispatch his gatherer to bring it in.

Buffaloes graze for five or six hours and you have to be with them all the time. When they have eaten enough, the herder takes them to a large, empty field so you can all rest. Buffaloes like to play with the large, beautiful cranes that gather in these fields. Cranes’ songs are very beautiful and so are their dances. The buffaloes lie on the ground and the cranes approach them to feed, sing, and dance.

The herder often relaxes by making up songs which imitate the sounds of the cranes. Vietnamese literature contains a lot of references to buffalo herding. Here is one of the traditional songs:

Who says buffalo herding is a tough job?

Sitting on the buffalo I dreamily listen to the birds up high

There are days I skip school and chase after butterflies by the pond bridge

Caught by mother, I cry even before the whip comes down

There is a young girl sitting by, watching me and giggling

Aren’t her round black eyes forever so lovely?

Cranes and Buffaloes inside Us

We have both the crane and the buffalo in ourselves. Taoists love cranes and often praise these birds for their quietude. Cranes are symbolic of nobility and calm. Zen practitioners compare the mind to a buffalo, which tends to wander and run after various distractions. A Zen practitioner is said to be a buffalo herder, keeping his or her mind from causing havoc.

Our mind has many parts; it does not have just one buffalo but a whole herd. Anger, blame, and resentment are not the good kinds of buffaloes. These emotions cause disturbances in our mind, and we have to know how to keep them in check. What are our tools to keep our minds from running wild?

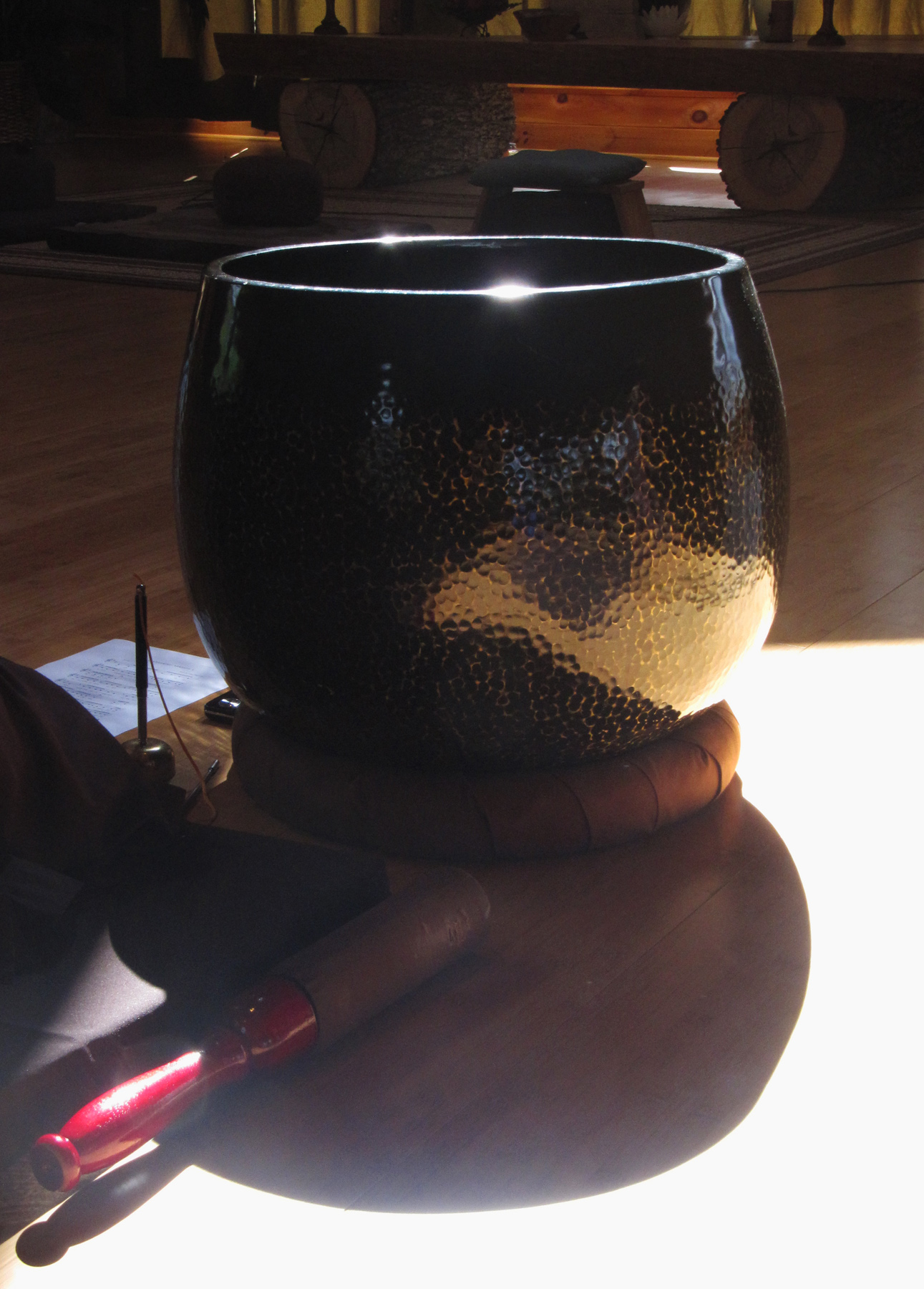

The rope we use to maintain direction over our buffalo mind is mindfulness. Mindfulness has the capacity to embrace mental formations that are running wild. When negative mental formations arise, we must recognize them immediately and ride the mindfulness buffalo after them. Recognition through mindfulness puts the negative mental formations on hold. How can we use mindfulness to take care of the scattering buffaloes? One good method is to do walking meditation, being aware of the breath and the steps. This form of meditation creates the energy of mindfulness so that we can take good care of our mind.

In order to generate the energy of mindfulness, certain conditions are necessary. A buffalo herder finds time to rest once he has taken his animals to a good grazing field. We must bring our mind to a spacious place so that it can rest and relax. We generate mindfulness so that we may take proper care of the wild buffaloes and the confusion of our mind.

When we come to a practice center, if we feel spacious and light as a crane, and if we feel there is nothing important we have to do, it means our mind has become relaxed and calm. We do not feel the need to meet the abbot or visit with monastics, because in our mind, the most important thing to have here is spaciousness for our practice. We create merit through our practice, not through contact with someone like the abbot. For the energy of mindfulness to arise more easily, we have to be calm and light as a crane, with a lot of concentration.

When we perform a deed in accordance with the Dharma, our mind is quiet and calm, and we work in mindfulness. When we learn about the Buddha and do everything in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings, we are performing a deed in accordance with the Dharma. Breathing in, I know I’m breathing in; breathing out, I know I’m breathing out—that’s breathing in accordance with the Dharma. When we arrange the cushions in the meditation hall, our hands pick up each cushion and place it carefully on the mat in alignment with the others. This is arranging the cushions in mindfulness, in accordance with the Dharma. If we do things with that mind, not being concerned whether a deed is large or small, then even if the work is as small as a speck of dust, the merit associated with the work is so large that it is indescribable.

Imagine seeing a cherished friend off at the train station. We don’t know when we’ll see him again. Our mind is totally concentrated on our friend, not distracted by other people or things. We are with him until the last moment when we shake hands as he boards the train. Our eyes follow the train until it disappears before we turn back. That memory, which we will carry in our heart forever, is possible thanks to mindfulness, which means that our mind is aware of the event that is taking place, and this awareness brings about a deeper understanding of life. That is our memory, and it can take us forward to the future. If we have a beautiful past, then our future will be joyful and beautiful, too.

When we come to the monastery, when we walk very slowly with our mind concentrated, it is a deep practice, and it becomes a part of our memory. When sharing a meal with the Sangha, we do it with a concentrated mind. We sit quiet and upright, let our mind relax, stop and breathe with the sounds of the bell, and have a deep appreciation for the food which is the gift of the earth and sky, as stated in the Five Contemplations. Aware that the food does not come by itself, we eat with deep gratitude. A meal like that, even simple, can be a good memory. It’s rare that we have an opportunity to share a meal with so many friends. Walking, eating, seeing a friend off, we always have the same sense of gratitude because we are aware that these opportunities don’t take place all the time. This awareness helps us feel intimate with life.

Connecting with Others

When we experience the joy of life deeply, we develop a close connection with others, and this generates within us a love for our fellow human beings. If we feel distant from others, it is a sign that we are also distant from ourselves and we lack a deep understanding of life. People are a part of life. The thought that we can stay away from people by living in nature is not logical, because people are part of nature. When we suffer from negative mental formations, we tend to blame it on other people, but the root cause of this suffering is the fact that we are not in touch with life and do not understand life. We may be competent in many fields of study, but we have not devoted enough time to understanding our own mental formations and those of the people living close to us. This creates a separation between ourselves and others, and life. When we live mindfully and wholeheartedly, we learn to be present so we can listen to the other person with an open heart, which relaxes and gladdens our mind. To be able to sit for a cup of tea or to share a conversation with someone, even for a few moments, makes wonderful memories that nourish us, helping us see that we are not alone on our life journey.

We cannot handle such negative mental formations as anger when we are not in touch with our own mind. But when we are mindful and in touch with life, we have a good “herd-gathering” buffalo which enables us to get hold of the anger at the level of mind consciousness, and take good care of it. Because they have such strong momentum, anger, worry, or sadness may not cease immediately when we recognize and try to embrace them. When this happens, we should not try too hard. When we see that the mental formation arising in us is creating tension, we should put only sixty to seventy percent of our attention on it. If the mental formation continues to run wild despite our effort, we develop the impression that we are helpless and powerless, and then our mind may become even more agitated. So we should pay only sixty percent attention to the mental formation, and save the other forty percent for relaxing and getting in touch with wonderful things around us. This is a useful technique when our concentration is not strong enough to completely embrace the negative mental formation and resolve it right away. Patience is important in this situation.

Equanimity is the absence of grasping. With equanimity, our mind is as unencumbered as when we take the buffaloes to the empty field. When the mind is able to observe anger, the anger is gradually subdued, and it merges with the mental formation of mindfulness. The runaway buffalo is gradually brought back by the “herd-gathering” buffalo, and the herd comes together as one. When anger is embraced with mindfulness, it becomes less strong, and it is transformed into the energy of mindfulness, like water and milk mixed together. We need to practice mindfulness diligently so that we gradually develop the capacity to embrace our anger and sadness. Once we are able to do this, we will be able to care for all other mental formations, such as jealousy, hate, love, etc. We begin with simple recognition, calling a mental formation by its true name as it arises. Then, also with mindfulness, we gradually embrace it, feeling the mind calming down, seeing that everything is mind. And when we can see the full depth of the mental formation and pull up its root, transformation happens. The buffalo herder and the Zen practitioner are similar in their approaches. Zen practitioners tame the buffaloes of our minds.

This is an excerpt from a Dharma talk given at Deer Park Monastery in January 2010.

Brother Phap Co was ordained in December 1999. He is Vietnamese Australian. He is very loved in our Sangha, because he is always positive and helpful to everyone. He loves to hike, bake bread, and work in the garden.