By Sulak Sivaraksa

Ed. Note: These insights are offered in response to Patricia Ellsberg’s article in the last Mindfulness Bell.

All Buddhists accept the Five Precepts (panca-sila) as the basic ethical guidelines. Using these precepts as a handle, we will know how to deal with the real issues of our day. The first precept is, “I vow to refrain from killing.” Killing animals and eating meat may have been appropriate for simple agrarian societies or village life,

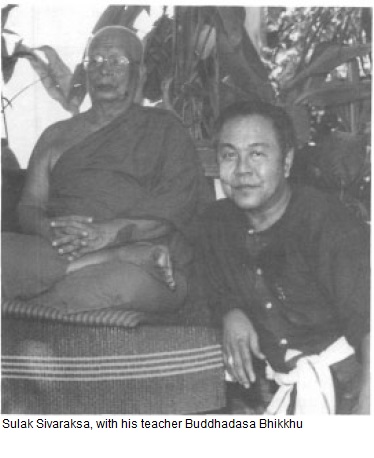

By Sulak Sivaraksa

Ed. Note: These insights are offered in response to Patricia Ellsberg's article in the last Mindfulness Bell.

All Buddhists accept the Five Precepts (panca-sila) as the basic ethical guidelines. Using these precepts as a handle, we will know how to deal with the real issues of our day. The first precept is, "I vow to refrain from killing." Killing animals and eating meat may have been appropriate for simple agrarian societies or village life, but in industrial societies, meat is treated as just another product, and the mass production of meat is not at all respectful of the lives of animals. If people in meat-eating countries could discourage the breeding of animals for consumption, it would not only be compassionate towards the animals, but also towards these humans living in poverty who need grain to survive. There is enough food in the world to feed us all. Hunger is caused by unequal allocation, even though often those who are most in need are the food producers.

We must look also at the sales of arms and challenge those structures that are responsible for murder. Killing permeates modern life—wars, racial conflicts, breeding animals to serve human markets, using harmful insecticides. How can we resist this and help create a nonviolent society? How can the first precept and its ennobling virtues be used to shape a politically just and merciful world? I shall not attempt to answer these questions. I just want to raise them for us to contemplate.

The second precept is, "I vow to refrain from stealing.'' In the "World-Conqueror Scripture" (Cakkavatti Sahananda Sutta), the Buddha says that once a king allows poverty to arise in his nation, the people will always steal to survive. Right Livelihood is bound up with economic justice. We must take great pains to be sure there are meaningful jobs for everyone able to work. We must also take responsibility for the theft implicit in our economic systems. To live a life of Right Livelihood and voluntary simplicity out of compassion for all beings and to renounce fame, profit, and power as life goals are to set oneself against the structural violence of the oppressive status quo. But is it enough to live a life of voluntary simplicity without also working to overturn the structures that force so many people to live in involuntary poverty?

The establishment of a just international economic order is a necessary and interdependent part of building a peaceful world. Violence in all its forms—imperialist, civil, and interpersonal—is underpined by collective drives for economic resources and political power. People should be encouraged to study and comment on the "New World Order" from a Buddhist perspective, examining appropriate and inappropriate development models, right and wrong consumption, just and unjust marketing, reasonable use and degradation of natural resources, and the ways to cure our world's ills. Where do Buddhists stand when it comes to a new economic ethic on a national and international scale? Many Christian groups have done studies on multinational corporations and international banking. We ought to learn from them and use their findings.

The third precept is "I vow to refrain from sexual misconduct" Like the other precepts, we must practice this in our own lives and not exploit or harm others. In addition, we have to look at the structures of male dominance and the exploitation of women worldwide. The structures of patriarchal greed, hatred, and delusion are interrelated with the violence in the world. Modern militarism is also closely associated with patriarchy. Buddhist practice points toward the development of full and balanced human beings, free from the socially-learned "masculine" and "feminine" patterns of thought, speech, and behavior, in touch with both aspects of themselves.

The fourth precept is "I vow to refrain from using false speech." We need to look closely at the mass media, education, and the patterns of information that condition our understanding of the world. We Buddhists are far behind our Muslim and Christian brothers and sisters in this regard. The Muslim Pesantran educational institutions in Indonesia apply Islamic and traditional principles in a modern setting, teaching their young people the truth about the world and projecting a vision for the future. The Quakers have a practice of "speaking truth to power." It will only be possible to break free of the systematic lying endemic in the status quo if we undertake this truth-speaking collectively.

The dignity of human beings should take precedence over encouraging consumption to the point that people want more than they really need. Using truthfulness as the guideline, research should be conducted at the university level toward curbing political propaganda and commercial advertisements. Without overlooking the precious treasures of free speech and a free press, unless we develop alternatives to the present transmission of lies and exaggerations, we will not be able to overcome the vast indoctrination that is perpetrated in the name of national security and material well-being.

The fifth precept is "I vow to refrain from taking intoxicants that cloud the mind and to encourage others not to cloud their minds." In Buddhism, a clear mind is a precious gem. We must look within, and truly begin to address the root causes of drug abuse and alcoholism.

At the same time, we must examine the whole beer, wine, spirit, and drug industries to identify their power base. We must overturn the forces that encourage intoxication, alcoholism, and drug addiction. This is a question concerning international justice and peace. Third World farmers grow heroin, coca, coffee, and tobacco because the economic system makes it impossible for them to support themselves growing rice or vegetables. Armed thugs act as their middlemen, and they are frequently ethnic guerrillas, pseudo-political bandits, private armies of right-wing politicians, or revolutionaries of one sort or another. The CIA ran drugs in Vietnam, the Burmese Communist guerrillas run drugs, and South American revolutionaries run drugs. Full-scale wars, such as the Opium War, have been fought by governments wanting to maintain the drug trade. Equally serious is the economic violence of forcing peasants to plant export crops of coffee or tea and the unloading of excess surplus cigarette production onto Third World consumers through intensive advertising campaigns.

Drug abuse and crime are rampant in those cultures that are crippled by the unequal distribution of wealth, unemployment, and alienation from work. Reagan and Bush's use of the U.S. armed forces to fight the drug trade is, in the end, just as pointless as was Gorbachev's campaign against worker alcoholism; both approaches address symptoms, not causes. Buddhism suggests that the only effective solution to these problems can take place in a context of a complete renewal of human values.

These basic ethical teachings apply to us as individuals and as members of society. My thoughts on the Five Precepts and how we might apply them to the situations of the world today are intended only as a first step. I hope discussion of these issues will continue. We need a moral basis for our behavior and our decision making.

Sulak Sivaraksa is a Thai Buddhist writer and social activist, presently in exile after criticizing the military junta in Thailand. This essay is excerpted from his new book Seeds of Peace: A Buddhist Vision for Renewing Society (Parallax Press, 1992).