By Brother Phap Lai, Kaira Jewel Lingo in October 2007

The Sangha in Vietnam, February–May 2007

In a letter from Hue, Brother Phap Lai wrote, “Tomorrow the Sangha flies and will land in Hanoi for the final leg of this 2007 ‘Sitting in the Spring Breeze’ Vietnam trip.”

These sketches from monastic and lay participants give us a glimpse into the power and beauty of the Sangha’s historic journey to Vietnam with Thich Nhat Hanh.

By Brother Phap Lai, Kaira Jewel Lingo in October 2007

The Sangha in Vietnam, February–May 2007

In a letter from Hue, Brother Phap Lai wrote, “Tomorrow the Sangha flies and will land in Hanoi for the final leg of this 2007 ‘Sitting in the Spring Breeze’ Vietnam trip.”

These sketches from monastic and lay participants give us a glimpse into the power and beauty of the Sangha’s historic journey to Vietnam with Thich Nhat Hanh.

Brother Phap Lai continues, “So far the ancestors, patriarchs and Vietnam’s present-day Sangha have been taking wonderful care of us, opening the door for the Dharma, for Thay and the Sangha to touch the hearts of so many people. The trip continues harmoniously although there is plenty of diplomatic work going on behind the scenes to help it be so. Thay is tired at times but you seldom know it as he shines, offering his best each and every day. At ease connecting with the old and new generations of Vietnam, whether it be monastics or devoted congregations of women, intellectuals, politicians or business people, Thay disarms folks with his warmth and humor.”

Flow

When I fi st stepped out of the airport of Ho Chi Minh City, I thought I would never survive crossing the amazing flood of motorbikes. How could I imagine the great lesson I would learn by first being forced to jump into this phenomenon, and then by looking deeply into it. This experience is all about the collective and individual management of constant change, of confidence and the vital importance of connection and absolute awareness of the present moment — “Go with the flow!”

—Dagmar Quentin

Ceremonies to Heal and Transform

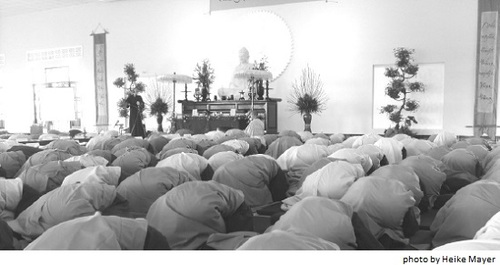

In Saigon [Ho Chi Minh City] the first of the three “Great Requiem Ceremonies to Pray Equally for All to Untie the Knots of Great Injustice” was conducted at Vinh Nghiem Temple. The second of these took place in Dieu De Temple in the ancient capital of Vietnam, Hue, which, as a battleground between the North and South, suffered terribly with many thousands of civilians killed. Thousands of lay people came to both Vinh Nghiem and Dieu De Temples over the course of the three-day ceremonies. Many Sanghas in the West as well as those in Vietnam who were unable to come conducted their own ceremonies in their own centers and homes.

The three days included daily Dharma talks by Thay in which he particularly encouraged us to generate wholesome, forgiving, and loving thoughts, and to purify the three karmas or actions of body, speech, and mind. Thay shared about the practice of beginning anew, even for those who have committed the worst of bodily actions. If we know how to begin anew and purify the mind of wrong thinking, then like a phoenix rising from the ashes we can free ourselves from the complex of guilt and despair to become a true bodhisattva. Thay also read several times “Prayers and Vows to Be Expressed During the Great Requiem Ceremony,” which set the spiritual intention and offered a common aspiration for all [see page 16].

In Saigon, ceremonies were led by Master Le Trang, Abbot of Vien Giac Temple, whose concentration and wholehearted intention as well as his expertise in chanting and mudras enriched the event tremendously. Each day it seemed he donned a different and more elaborately embroidered sanghati. For the opening ceremony Thay was persuaded to wear the dress reserved for the highest master. After that Thay was happy to return to wearing his own simple sanghati.

As well as the dress many of the ritual instruments and other ornamentations are rarely if ever used, instead being preserved as precious antiques, relics of the tradition. Traditionally dressed musicians playing the old instruments — percussion, a single stringed box guitar, and a reeded woodwind horn — accompanied the chanting master and the processions in general. Monks also sounded conch horns at various stages of the procession. The musicians were able to continuously follow, build, and crescendo with each nuance of the chanted texts for the whole three days. Their contribution was magnificent. The second evening ended with a grand procession of monastic and lay people to set thousands of candles in origami lotus flowers floating down the river along with our prayers and vows for those who were killed in the Vietnam war. In Hue a similar event had our whole sangha board a flotilla of large tourist boats and after some time traveling upstream we congregated to set the lighted candles on the Perfume River while chanting. The image of hundreds of floating candles emitting their soft light could not fail to touch our hearts and the onlookers from the bridge.

In Saigon, the entire floor area underneath the Buddha Hall was converted into a maze of altars draped with golden yellow fabrics. Incredible artistry went into decorating many altars, each with their own bodhisattva, some fierce looking, some gentle. Part of this was an inner sanctum that served as the main area for the long chanting sessions. During these sessions only monastics could enter in order to generate and maintain the high level of concentration necessary. Lay people followed these on a big screen outside but at various points the chanting master would lead a procession outside to the temple gates and back. Outside the inner sanctum altars held food offerings and lists of hundreds of loved ones with the date they were killed in the war. After the very final chanting of the three-day ceremony at 2:00 a.m. all the decorations, altars, papier-mâché statues made especially for the Grand Requiem Ceremony and the lists of countrymen and women who died were burned together as an offering.

With the support of the monastic and lay community of Saigon and the cooperation of government officials, the ceremony that took place in Saigon was a major success. Mass ceremonies of this scale and intention are a unique occurrence in Vietnam. It is not surprising they are controversial — they bring up past suffering and require acknowledgment that great injustices were suffered on both sides. It has not always been possible to attain the official acceptance of a ceremony that acknowledges that people suffered unspeakable injustices on both sides and that asks that we pray equally for all without any discrimination across the old divides of geography and ideology, man and woman, civilian and the army. Imagine previously warring nations coming together in this spirit and one begins to understand the significance of these ceremonies, the potential healing but also the obstacles in the mind that prevent them from taking place.

—Brother Phap Lai

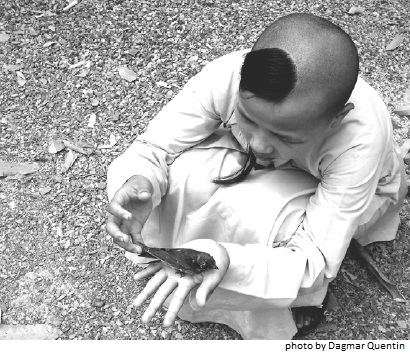

A Miracle at Bat Nha

In the magical mountainous region described by Thay in Fragrant Palm Leaves near the town of Bao Loc, Lam Dong province, about six hours north of Saigon, is Bat Nha Temple. Sadly, much of the ancient rainforest once inhabited by tigers has been cleared for coffee and tea plantations. Many in this region form the ethnic minorities of Vietnam. A long tradition of trust has developed between these indigenous people — some of whom ordained at Bat Nha — and our community, thanks to long-time funding for social projects from Plum Village. Arriving in Bat Nha, we were hosted by some three hundred young monks and nuns, nearly all under twenty-five, who were ordained as novice monastics under Thay since the last Vietnam trip in 2005. At that time the Abbot Duc Nghi, a devoted follower of Thay, offered the temple to Thay and the Sangha. Since then, with funding from the Western Sangha via Plum Village and lots of dedicated work from the Sangha and local people, many new buildings have sprung up including a very large Dharma hall, the Garuda Wings Hall, and two residences for the hundreds of newly ordained.

The first major event held in Bat Nha on this trip was a four-day residential retreat for lay people. Prior to the retreat the limit of those registered had been set at 2000 but by the evening before we had more than 4000 names registered. After hearing that a full bus of people from Saigon (six hours away) had been turned back by the monastery guards because they weren’t registered, Thay made it clear he did not want to turn away anyone who had come for the Dharma. But numbers were growing and where to house everyone? As planned the big new hall was used as one dormitory but many more had to fit in than was first intended. For instance, the football field with the help of acres of tarp was transformed into a dormitory for 1000. From the first day the cooks say they prepared for 7000 but there were as many as 10,000 people on the Sunday of Mindfulness. Considering the huge number of people attending everything went extraordinarily well. The registration team kept their cool, practicing mindfulness and compassion, and all who came found a place to sleep and go to the toilet! The cooking teams of Bat Nha’s brothers and sisters along with local supporting lay friends performed daily miracles preparing three good meals a day for everyone. Forty lines for food provided a good flow and everyone was able to eat together in families at one sitting.

—Brother Phap Lai

Phuong Boi Ordination

Our time together on this trip has given the monastics of Plum Village and the centers in the United States and our young brothers and sisters in Vietnam a chance to meet. In Bat Nha we enjoyed drinking tea, making music, working together, two rather serious games of soccer and the odd dramatic downpours from broody evening skies.

The last week in Bat Nha included a five-day Grand Ordination Ceremony given the name “Phuong Boi” (Fragrant Palm Leaves). It included transmission of the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings to 100 monks and nuns and forty lay practitioners, all Vietnamese with the exception of our German brother Kai presently living in Hanoi. There was also a ceremony to transmit the ten novice precepts; it is always an exciting and heart-warming day when a new family of novice monastics are brought into the Sangha. We now have the sweet young Sandalwood family of eighty-nine young novices in our fold. An age range of 15 to 25 limits the numbers although there were some exceptions.

Fifty-three bhikshus [monks] and fi y-four bhikshunis [nuns] were ordained by a special envoy of Venerable Monks who came especially to form the official presiding Ordination Committee. The Lamp was transmitted by Thay to twelve new Dharma Teachers.

—Brother Phap Lai

Receiving the Lamp Transmission

Several of you asked me before I left about my gatha. It really started to come together when we visited a beautiful waterfall near Bat Nha. I sat there watching the 200-meter-tall streams of water falling and felt so peaceful and calm. Then I saw this old, kind face in the rock, smiling mischievously to me! I had to laugh back. My father [OI member Al Lingo] was one attendant for the Lamp Transmission, Sr. Dao Nghiem, a younger sister from the Persimmon family, was the other. I shared a little in Vietnamese at the beginning and cried quite a bit. I spoke mostly about my gratitude to Thay and the Sangha, and about my monastic path as a journey of self-acceptance. I sang “Amazing Grace” at the end.

This is my gatha:

A face in the wet rock smiles to me Wise, loving eyes twinkle with laughter Everything I need is already here I am totally at ease Before I was born, my work was already accomplished At every stage of manifestation we are complete There is no final product. No progress needs to be made. You don’t have to change! Just be yourself, love yourself It is the only way to make progress. Let go, fall without fear Like the waterfall, dancing its endless dance of freedom. Wheeee!

—Sister Jewel, Chau Nghiem

Bowing to the Mystery

Following Thay and the monastics our Western delegation moves into the An Quang Temple in Saigon. We are greeted by Vietnamese men and women in the same grey temple robe we are wearing on this trip. Again a woman bows to me, her hands folded in front of her heart. I stop and return the bow. As we both straighten up and look at each other, she has tears in her eyes — and me too. How old is she, seventy, eighty years maybe? What may she have experienced during the war? Who does she see in me? What do I represent? I allow myself not to know, as I so often do on this trip. I practice simply trusting that Thay’s wish to bring healing and transformation to Vietnam will be fulfilled and that wondrously I can make a tiny contribution to it.

—Heike Mayer

Treasure of Healing

I was so moved by the chanting and Grand Requiem Ceremonies in Saigon. Many of us had powerful experiences of connection and healing and reconciliation. I touched my own ancestors in a new way during the last night of eight hours of straight chanting. I felt their presence and their happiness, even those I never knew. I also felt connected to the many land ancestors throughout the history of the U.S.—all the injustices and tragedies they suffered, from the decimation of native peoples, slavery, to the many wars. I invited them to come into the space we created for healing, for peace. I was surprised that I could sit still for so long, peaceful, concentrated, and present. The monks who led the chanting and all the thousands of people practicing with us outside the hall at Vinh Nghiem temple created a powerful atmosphere of transformation. Afterwards, instead of feeling tired I was energized by this rare and precious event.

Sister Chan Khong told us many monasteries brought out statues and artifacts for the ceremonies that had not been publicly displayed in years — national treasures held in secret for preservation. Many sanghas joined to host this event, unprecedented in Vietnam on such a large scale. I feel so grateful to Thay for holding his vision. In the West, we have so many unhealed, misunderstood, unacknowledged wounds. If only we had taken time to be with the suffering of the Vietnam war, to recognize and heal it, the war in Iraq would never have happened.

--Sister Jewel, Chau Nghiem

Kitchen Mindfulness

I was on a cooking team at Tu Hieu for working meditation. In the kitchen as we made breakfast starting at 3:30 a.m., the energy was peaceful and calm, everyone still sleepy and soft. Everywhere in Vietnam we cooked with wood. One of my favorite jobs was to sit in front of the stove fanning the fire. I did whatever task I was given, finding each enjoyable. Many lay people came to help—even lay men cooking along with women! Once when we were making lunch, we ran out of things to do at 9:00 a.m. so we all sat in the dining hall and taught each other songs until the food arrived. Just being together, the smiles, the care, we weren’t really there to work, yet everything happened as it needed to and the meals were always on time.

—Sister Jewel, Chau Nghiem

A Chorus of Grass Birds

Today, after sitting meditation we practiced walking meditation through the peaceful temple grounds of Thay’s root temple in Tu Hieu. We gathered to sit silently in a circle on the same grass where he played as a child monk. I was four feet from Thay — just breathing, smiling, joyous — a treasure I will never forget. Then he delighted us all — picked a wide blade of grass, put it in

his palm, and suddenly impishly blew, making grass sound like a bird — gleeful as a boy! This started a chorus of monks and nuns chirping with their own grass leaves, a veritable bird chorus! A light private moment, a glimpse into the playfulness of a forever young 82-year-old poet.

—Harriet Wrye

An Offering of Shoes

During the last powerful evening of chanting in Hue, I was really present for myself, for my inner child, and for the many who died in the war, seeing them healed, happy, restored. When the monks blessed the rice and threw it into the crowd, people began to push and shove us, trying to get some of the rice. They believe if they make soup from rice blessed in such an important ceremony, any sick person who eats it will heal. So I got up from quiet sitting to become a bodyguard for the chanting monks! Holding back the rowdy crowds, I’ve never seen my sisters so tough.

My shoes stolen, I walked barefoot in the mud among fallen food offerings to burn paper tablets on the ancestral altar, ending our ceremony. Many of our shoes were taken that evening. One barefoot brother casually said, “It was an offering”!

—Sister Jewel, Chau Nghiem

“Each of My Steps Is a Prayer”

Upon touching down in California after the Vietnam pilgrimage I felt like I had been put through the wash, then spun partly dry. As a dietitian it’s easy for me to say there was a lot to consume as we went from Ho Chi Minh City to the north in a short time. I see that it took all the ingredients of Vietnam’s wars, including over six million deaths, to have conditions necessary for a compassionate teacher to conduct extraordinary ceremonies of reconciliation and healing. Concurrently, many of us pilgrims were advancing our own personal transformations by leaving our cozy, familiar world to join in one or more of the journey’s segments. My personal experience in several Great Requiem Ceremonies untied my own knots of great injustice. This seemed to be so for others I talked with along the way. We were fortunate to be Thay’s supporting cast during his epic reconciliation and healing production, students and teacher practicing in the spring breeze of Vietnam.

Everyone’s effort, using a solid-as-a-mountain practice, helped transform the government’s distrust of Thay’s sincere intention to help the situation in his homeland. It was amazing to be at dozens of talks, at retreats and ceremonies with tens of thousands of Vietnamese. For most, it was their first glimpse of Thay, the mysterious, most venerable who transforms the suffering of the West and East. To observe Thay’s presence and focus while big crowds bowed, chanted and touched the earth before him was unforgettable and humbling. Westerners who posted words and images during the 2005 trip inspired me to share pictures and a blog. The teacher in me wanted to help sangha friends and family stay tapped in as events unfolded. As a final offering to the Sangha, I produced a 42-minute video, “Each of My Steps Is a Prayer” — words Thay used to describe his practice — presenting sounds and images of transformation and beauty in Vietnam. I am donating the video to the Sangha as a way to raise funds for Vietnam’s monastics.

The video is currently in English and works on NTSC DVD players; a version formatted for European PAL players is also available. Please send two checks or money orders, one for a tax-deductible $13.00 donation made out to “UBC Deer Park” and the other $3.00 for shipping made out to “David Nelson,” to: David Nelson VN07, 4360 Jasmine Avenue, Culver City, California 90232. Make sure to include your shipping address.

—David Nelson