Thích Nhất Hạnh offers a deep teaching on the futility of hate and discrimination, and on the insight of interbeing and nonduality as the way to liberation and non-fear.

By Thich Nhat Hanh on

Listen Śāriputra, all phenomena bear the mark of Emptiness; their true nature is the nature of… no Defilement, no Purity

“Defiled or immaculate” and “dirty or pure” are concepts we form in our mind.

Thích Nhất Hạnh offers a deep teaching on the futility of hate and discrimination, and on the insight of interbeing and nonduality as the way to liberation and non-fear.

By Thich Nhat Hanh on

Listen Śāriputra, all phenomena bear the mark of Emptiness; their true nature is the nature of… no Defilement, no Purity

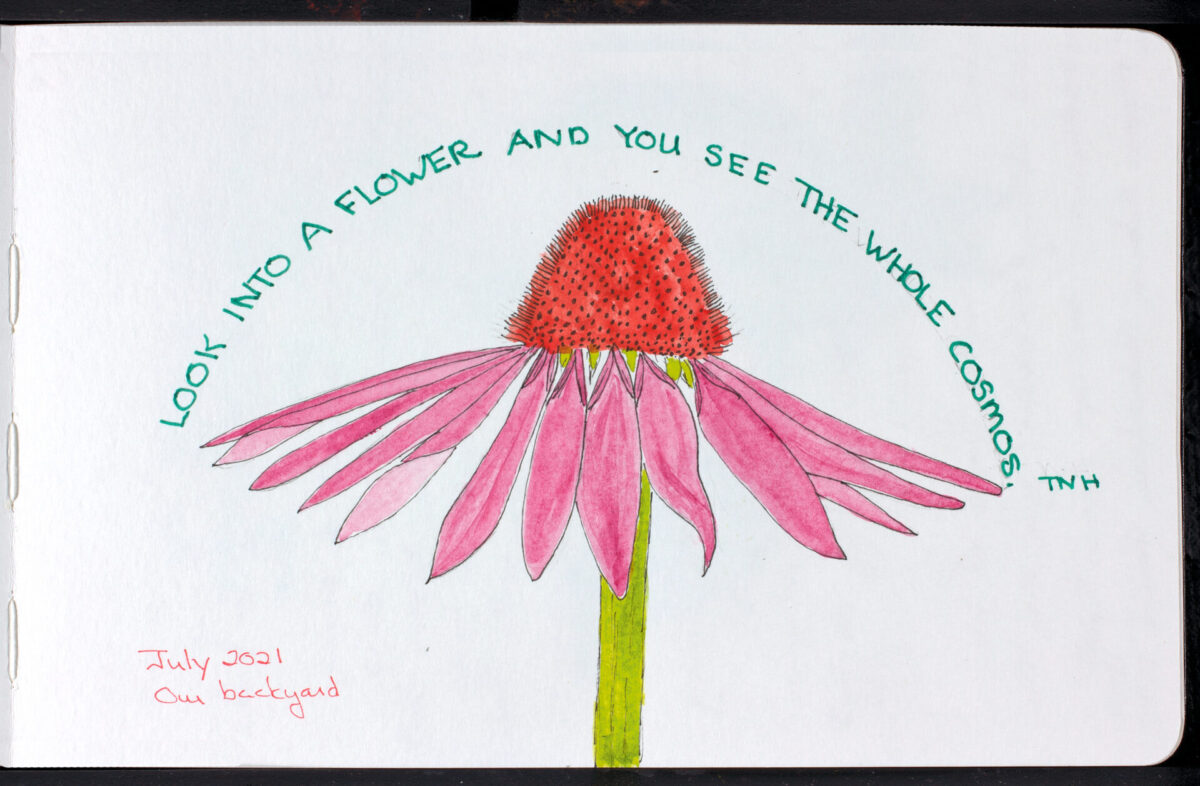

“Defiled or immaculate” and “dirty or pure” are concepts we form in our mind. We see a beautiful rose in a vase and think it is immaculate. Its fragrance is pure and fresh. It supports our idea of purity. The opposite is a garbage can. It smells horrible and is filled with rotten things. We identify this as defiled. But if we look deeply at the concepts of defiled and pure, we have a chance to touch the insight of interbeing.

If you are a good organic gardener, if you have the eyes of a bodhisattva, looking at a rose you can see the garbage, and looking at the garbage you can see a rose. Roses and garbage inter-are.

In just five or six days, the rose will become part of the garbage. We do not need to wait five days to see this. If we just look deeply at the rose, we can see it now. And if we look deeply into the garbage can, we see that in a few months its contents can be transformed into a rose.

If you are a good organic gardener, if you have the eyes of a bodhisattva, looking at a rose you can see the garbage, and looking at the garbage you can see a rose. Roses and garbage inter-are. Without a rose, we cannot have garbage; and without garbage, we cannot have a rose. The rose and garbage are equally important. The garbage is just as precious as the rose.

Neither Good nor Evil

Politically, if the right is not there, how can you be on the left?

We are imprisoned by our ideas of good and evil. We want only good, and we want to remove all evil. But that is because we forget that good is made of non-good elements. Suppose we hold a lovely branch in our hand. When we look at it with a nondiscriminating mind, we see a wonderful branch. But as soon as we distinguish that one end is the left and the other end is the right, we get into trouble. We may say we want only the left, and we do not want the right, and there is trouble right away. Politically, if the right is not there, how can you be on the left? Let us say that we do not want the right end of this branch, that we only want the left. So, we break off half of this wonderful reality and throw it away. But as soon as we’ve done this, the end that remains becomes the new right—because as soon as the left is there, the right must be there also. If we become frustrated and do it again, breaking what remains of the branch in half, we will still have a right and a left.

The same may be applied to good and evil. You cannot have only good. You cannot hope to remove evil completely, because thanks to evil, good exists, and vice versa. When you put on a play about a heroic figure, you have to provide an antagonist in order for the hero to be a hero. In Buddhism, the antagonist is named Māra, the demon who attempted to distract the Buddha from reaching enlightenment. The following story about Buddha and Māra reflects the Buddhist insight into the relationship between good and evil.

When Māra came in, the Buddha stood up to greet him as if he were a special guest, invited him to sit in a place of honor, and took his hands in his in the warmest way.

One day the Buddha was in his cave, and Ānanda, who was the Buddha’s attendant, was standing outside near the door. Suddenly Ānanda saw Māra coming. He was surprised. He didn’t want that, and he wished Māra wouldn’t notice him and would go away. But Māra walked straight up to Ānanda and asked him to announce his arrival to the Buddha.

Ānanda said, “Why have you come here? Don’t you remember that long ago you were defeated by the Buddha under the bodhi tree? Aren’t you ashamed to come here? Go away! The Buddha will not see you. You are evil. You are his enemy.”

When Māra heard this, he began to laugh and laugh. “Did you say your teacher has enemies?” That made Ānanda very embarrassed. He knew that his teacher had not said that he has enemies. So Ānanda was defeated and had to go in and announce Māra, hoping that the Buddha would say, “Go and tell him that I am not here. Tell him that I am in a meeting.”

But the Buddha was very happy when he heard that Māra, such a very old friend, had come to visit him. “It’s Māra? Let him come in!” the Buddha said. Ānanda was distressed. When Māra came in, the Buddha stood up to greet him as if he were a special guest, invited him to sit in a place of honor, and took his hands in his in the warmest way. The Buddha said, “Hello Māra! How are you? How have you been? Is everything all right?”

The Buddha asked Ānanda to go and make herbal tea for both of them. “I’m happy to make tea for my master one hundred times a day, but making even one cup of tea for Māra is miserable,” Ānanda thought. But since this was the order of his master, how could he refuse? So Ānanda went to prepare some herbal tea for the Buddha and his so-called guest, but while doing this he tried to listen in on their conversation.

The Buddha repeated very warmly, “How have you been? How are things with you?”

Mara said, “Things are not going well at all. I am tired of being Māra. I want to be something else—maybe someone like you. Wherever you go you are welcome, people bow before you and make offerings.”

Hearing this, Ānanda became very frightened. Māra said, “You know, being a Māra is not a very easy thing to do. If you talk, you have to talk in riddles. If you do anything, you have to be tricky and look evil. I am very tired of all that. But what I cannot bear is my disciples. They are now talking about social justice, peace, equality, liberation, nonduality, nonviolence, all of that. Before, they used to listen to everything I told them. Now they are in revolt. The commanders of my army are demanding to do sitting meditation. Can you believe it? They want to practice mindfulness, do walking meditation, eat in silence, protect life, protect the environment and the Earth. They are driving me mad. I do not know who is influencing them. I have had enough of it! I think that it would be better if I hand them all over to you. I want to be something else. Maybe we could change roles.”

At this, Ānanda began to shudder with fear. Māra would become the Buddha, and the Buddha would become Māra. It made him very sad.

The Buddha listened attentively and was filled with compassion. Finally, he said in a quiet voice, “Do you think it’s fun being a Buddha? You don’t know what my disciples have done to me! They put words into my mouth that I never said. They build garish temples and put statues of me on altars in order to attract bananas and oranges and sweet rice, just for themselves. And they package me and make my teaching into an item of commerce. Māra, if you knew what it is really like to be a Buddha, I am sure you wouldn’t want to be one.”

• • • • •

In the West, we have been struggling for many years with the problem of evil. How is it possible that evil exists? It seems difficult to understand. But in the light of nonduality, there is no problem: as soon as the idea of good is there, the idea of evil is there. Buddha needs Māra in order to reveal himself, and vice versa. Buddha is as empty as the sheet of paper; Buddha is made of non-Buddha elements. When you perceive reality in this way, you will not discriminate against the garbage in favor of the rose. You will cherish both.

The Problem of Names

For many years, the United States has been trying to demonize other countries, from North Vietnam, to the countries of the former Soviet Union, to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. Some Americans even have the illusion that they can survive alone, without these other countries. Other countries may believe that they, too, can exist without the US. They call the United States the American imperialists or the infidels and believe the US must be eliminated for happiness to be possible. But that is the dualistic way of looking at things. It is the same as believing that the right side can exist without the left side. If you take sides, you are trying to eliminate half of reality, which is impossible.

Israel and Palestine are two hands of the same body.

If we look at the US deeply, we see Iran. If we look deeply at Iran, we see the US. In international politics, each side pretends to be the rose and calls the other side the garbage. Recently, a young person asked me, “Why do we give different names to different things, since they’re really together, they’re really one?” That was a very good question. I replied, “Names are at the root of so many problems. We give places different names, like America, Iran, and Iraq. But in fact they all belong to the Earth. Israel and Palestine are two hands of the same body.”

You have to work for the survival of the other side if you want to survive yourself. Survival means the survival of humankind as a whole, not just a part of it. This is true not only for the United States and the Middle East, but also for the East and West, the North and South. If the southern nations cannot survive, then the northern nations too will crumble. If developing countries cannot pay their debts, everyone will suffer. If we do not take care of poorer countries, the well-being of richer countries is not going to last, and we will not be able to continue living in the way we have been used to for much longer. Only when we can touch the wisdom of nondiscrimination in us can we all survive.

In the Majjhima Nikāya, one of the collections of the Buddha’s discourses, there is a very short passage on how the world has come to be. It is very simple, very easy to understand, and yet very deep: “This is, because that is. This is not, because that is not. This is like this, because that is like that.” This is the Buddhist teaching of Genesis.

Our lives are like this because other lives are like that. The citizens of every country are human beings. We cannot study and understand a human being just through statistics. We can’t leave the job to governments or political scientists alone. We have to do it ourselves. If we arrive at an understanding of the fears and hopes of a citizen from Iraq or Sudan, Afghanistan or Syria, then we can understand our own fears and hopes. If we have this very clear vision of reality, we do not have to look very far to see what we have to do.

We are not separate. We are inextricably interrelated. The rose is the garbage, the soldier is the civilian, the criminal is also the victim. The rich man is the very poor woman, and the Buddhist is the non-Buddhist. “This is like this, because that is like that.” No one among us has clean hands. None of us can claim that the situation is not our responsibility. The child who is forced to work as a prostitute is that way because of the way we are. The refugees who are forced to live in camps have to live like that because of the way we live. The arms dealers do their business so that our economies can continue to grow and they can benefit. This helps to create that, and that helps to create this. Wealth and poverty, the affluent society and the poor society, inter-are. The wealth of one society is made of the poverty of the other. Wealth is made of non-wealth elements, and poverty is made of non-poverty elements.

We are responsible for everything that happens around us. If we look into ourselves with the eyes of interbeing, we see the young prostitute, the child soldier, the starving mother, and the migrant worker; we bear their pain, and the pain of the whole world. It is from this insight of interbeing that true compassion will be born in our hearts and we will know what to do and what not to do to help the situation.

This is an excerpt from The Other Shore by Thích Nhất Hạnh, published by Parallax Press.