Excerpts from a Panel Discussion

Paths to Community Justice

By Cheri Maples

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

August 24, 2016

Good evening, everybody. Thanks for being here. I’m really happy to be spending the time with you.

There are a couple of things I’m really passionate about right now.

Excerpts from a Panel Discussion

Paths to Community Justice

By Cheri Maples

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

August 24, 2016

Good evening, everybody. Thanks for being here. I’m really happy to be spending the time with you.

There are a couple of things I’m really passionate about right now. One is building bridges, particularly between police officers and the communities they serve, because there’s never been more of an “us and them” mentality, ever. It’s very, very challenging, and there is so much going on. Looking at various policies, the major public safety tool I’m interested in is building neighborhood capacity, because this is what creates public safety. Getting creative with the tools we use is important.

The other thing is—and we see it in the political arena and on down—that “compassion” is a dirty word, associated with weakness of some kind, which couldn’t be further from the truth. You have to be a much stronger warrior to be compassionate than you do to be physically aggressive with somebody. In learning how to be compassionate, you have to really open up your heart. You can’t walk around with an armored heart and yet to do the work; it armors your heart. There’s sort of a “Catch-22.” Learning how to balance the passion with equanimity is a real passion of mine.

Another real passion is working with white people around race awareness—particularly in the criminal justice system, where the racism is so obvious, so institutionalized—and building coordinated community efforts around creating public safety. The person who sums it up well is Cornel West, who said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” It’s the model I aspire to have, and it drives what I do—that definition of justice.

Something I’ve found about mindfulness is that it was a tool that provided me with some emotional resiliency to deal with some of the things that had happened to me over the course of my career. It also inspired me to always have the intention in front of me as a street cop to bring no further harm to the situation I was responding to, even if it meant sometimes using force to prevent people from harming each other. But when things turned around for me, and what was very interesting, is that after my first retreat I came back and I really couldn’t understand what they’d done in my absence. Everybody had gotten so much kinder, even the people I was arresting. This was a real huge message to me, and it started the process.

Gifts of Mindfulness

A real danger about the popularity of mindfulness is misunderstanding what it is. It isn’t just a relaxation tool and it isn’t just a medical model. There’s an entire ethical framework that goes along with it. If you separate the two, there is a lot of danger. Most of the values that are inherent in mindfulness have to do with non-harming in some way. You can be an advocate for peace and justice and still go to war with people on a daily basis with the words you use. We’ve all seen it.

When I teach mindfulness, I start by having a big flip chart with a white piece of paper, and I put a little red dot in the middle and I say, “What do you see here?” And everybody says, “I see a red dot.” And I say, “That’s the problem. That’s where we live. We live in the red dot rather than the white space.” In mindfulness, what I’ve found is a tool that helped me to live in that white space in a remarkable way.

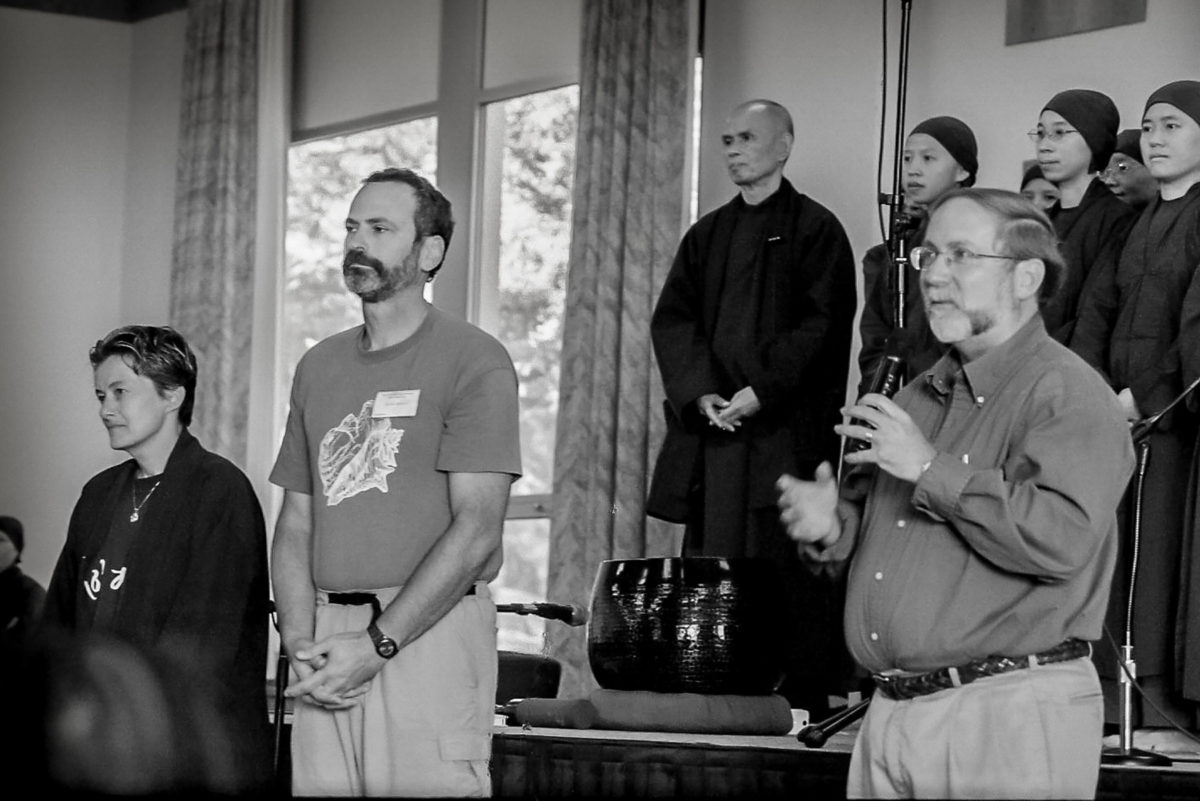

One thing that helped me in terms of my work is that in the Thich Nhat Hanh tradition, there is a big emphasis on building Sangha and looking at Sangha as an organism rather than an organization. So I started looking at everything I was part of as community, whether it was my family, my workplace, organizations that I was on the board of, anything that I was doing became, “Okay, this is a Sangha, this is a community.” And how do we build this? It led to my starting to see myself as an effect of a lot of the things that went on around me rather than the empowerment of seeing myself as a cause. In other words, it drives me crazy these days when I go to meetings and people walk out and say, “That was really a shitty meeting,” and I say, “Well, were you there? [Laughter]. You were part of helping create that meeting.”

How we witness violence, exploitation, in all of its manifestations—how we bear witness to it—is such an opportunity to transform things. The skills mindfulness leads to—one of the major ones—is pausing and refraining. The ability to put space between your thoughts and your words and your thoughts and your actions is huge in terms of transformation. But the biggest gift of mindfulness has been understanding that my mind is not an accurate reflection of the world, that it is a result, that my perceptions are so conditioned they don’t match reality, and that the truth has many sides.

When I try to get people to understand this, I do this exercise: I’ll have three people leave the room and I’ll say to everybody else, “Build me a structure, but it’s got to be a structure that can be put back together in two minutes. Use what’s in the room.” Then I’ll have the three people come in one at a time and stand in exactly the same spots and say, “What do you see?” The most interesting time I’ve ever done this, these were the three responses:

“I see George Washington on the Potomac River.”

“I see chaos and homelessness.”

“I see art and sculpture.”

Then my question is: Who’s right? Who’s wrong? I don’t know.

You know the bumper sticker, “Don’t believe everything you think”? Until you have an experience of this, it’s hard to take in other viewpoints in a way that matters. It’s hard to be present to another human being until you truly understand from your heart that your mind is not an accurate reflection of the world and that it’s created over and over again in this moment. I’ve seen absolutely horrendous things individuals do to each other that systematically happen as a result of poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia; as a cop, something that started happening for me is that all of those things got covered up with anger and with a numbing of the heart, an armoring of the heart. You can’t respond to people from that place. So mindfulness was a tool to undo all of this for me and it was an incremental process over time.

Once I got to be the captain of personnel and training and had my own team, I could do something as simple as going around and saying, “Hey? What’s the biggest frustration?” It was always gossip. You wouldn’t believe how police gossip passes. It’s like being back in high school except everybody has a gun. [Laughter] It’s really scary. So I asked, “What if we make an agreement that if we have a complaint, we’ll take it to the person we have it with or somebody who can do something about it?” I said, “Hey, I’m not gonna be around [because we were all in different buildings], so you have to hold yourselves accountable and each other accountable. I don’t want to even engage in it unless that’s something you’re willing to do.” They did. Then they brought it to the recruits as a way of being with each other, and it was the most pleasant team experience I ever had in my life.

One thing mindfulness brought me in terms of creating community is to look at whatever community I’m a part of. There are unconscious, unwritten rules people are socialized to. We have the Tea Party of the right, but we also have the Tea Party of the left. We have fundamentalists everywhere, and there’s a certain socialization that goes on with it. I know what it was in my arena, and mindfulness taught me to bring those unwritten and unspoken rules into the conscious arena for discussion. It’s how you change the ethics of any given organization.

Even in terms of race, one thing I do when I work with organizations is to have them identify every decision-making point in the organization where race could be a factor in their decision-making. When I was associated with probation and parole, they said to me, “We just get what people give us. We’re not responsible for that.” I sat down, and we made a list of four pages of things they’re all involved in where race could be a factor in their decision-making.

Much of this is about awareness, about being a good curator of the museum of our past, taking care not only of our individual seeds but also of those collective seeds that we are all socialized to, and then being a good gardener of our store consciousnesses. If we are aware, we can make conscious decisions about what behaviors we keep and don’t keep, and then life gets much more interesting and much more fun—and much sadder. You can’t have one without the other, and the pain to me is something I now know how to use to tenderize my heart, while it used to be something I just raged about.

Those have been some of the gifts of mindfulness for me. It’s been a journey, it’s been a practice of learning to bring it to everything I do, and it’s been about forming a real intentionality. Every way of transformation I’ve ever heard about starts with declaring an intention and affirming it over and over because “you are what you eat.” And that is so important.

Once I did an exercise that was very valuable to me. Somebody said to me, “If your life continues on the path that it has up until now, really getting honest with how it has been up til now, what will your predictable future be?” This had a huge impact on me. It made me think about what is it I want to do? What is it I want to be about? What is it I want to affirm over and over on a daily basis? I don’t think transformation can happen without that kind of intentionality. And it’s not just mindfulness; there are all kinds of tools we could use to be good curators of the museums of our past as well as good gardeners of our store consciousnesses. We might not ever have been exposed to “mindfulness” and yet be very good at doing these things.

Working for Justice

I came to the practice as a community organizer before I was a cop. I worked in the largest federal housing project in Milwaukee, in deferred prosecution programs, in the violence against women movement, and I was pretty full of rage. In fact, I remember being part of a panel like this and somebody in the audience said, “You all seem so angry here.” I said, “Well, aren’t you?” I just couldn’t conceive that somebody wouldn’t be.

I’d like to go back to what I was trying to say before about reality: There’s something that happens, there’s your perception of that, and there’s your story in between. If I’m a cop and I see someone swerving all over the traffic lines and I stop them, expecting only to see a drunk driver, I’m gonna miss the diabetic who’s right in front of me. So this whole thing of really being aware of larger possibilities, including the possibility that I may not be right and that the truth has many sides, has had a huge impact on me and the way that I look at and respond to things. The practice of mindfulness has helped me in that way; however, it’s not going to solve systemic injustices, so it’s really important to work both individually and collectively.

The Black Lives Matter movement has been so huge in calling out what’s going on and the organizing around it. This is where communities have to take a stand, all of us—a huge gap exists between what cops are trained to do, which is legal, and what the community believes is moral. As long as this gap exists, it’s not going to be safe for anybody. Police officers need to recognize as long as that gap exists, it’s not safe for them either. So I think communities really have to bring attention, first and foremost, to that gap. The whole police department is responsible for looking at that gap and being a part of changing it.

The racial disparities are absolutely ridiculous. I see how they work; I’ve seen how they work in every part of the system. If I expect Ford drivers to commit more crimes than Chevy drivers, I could just sit outside Ford dealerships. I’m gonna go where Ford drivers are likely to be and stop a lot more Ford drivers twenty-six times; I’m gonna stop a lot more Ford drivers than Chevy or any other kind of driver; and because I arrest more as a result of the disproportionate stops I make, I’m going to confirm my own bias. So the role of mindfulness in this to me is interesting. You can slow down that whole decision-making process. Cops can slow down that whole decision-making process and ask themselves, “Why am I stopping this person? What’s the decision-making process?”

All of us can do these things, but what’s first really, really important for us to do collectively is to create informal safety nets. Without creating informal safety nets and without building neighborhood capacity, public safety is not going to exist in the form we want it to exist. I’m a big supporter of changing definitions. In my own community, this thing called the Time Bank exists, which I love because it changed the definition of money and value. The Time Bank says that one hour of your time, no matter who you are, is worth one hour of my time, no matter who I am.

It’s not that the kid who works at McDonald’s gets paid this and that a lawyer gets paid $250 or $300; we all have strengths, we all have things we offer, and we all have things we need. One thing that really bugs me about the volunteer model we use in a lot of places is a superiority that comes with it when you’re giving but you’re not learning anything about receiving. For example, I heard a microaggression the other day in a group of white people who teach mindfulness in prisons. A woman said, “One of the things I think we have to do is to help people understand their strengths.” I looked at her and thought, “How can you help them identify their strengths? What if they helped you identify your strengths and how you could be of service to them?”

The superiority that comes with this kind of assumption is sort of mind-boggling, and those microaggressions exist all the time. And I don’t know what the answer to this is. I don’t know how people of color heal from racism in this country and from the damage that has been created. I mean, as a white person, I’m perceiving more and more layers of it all the time. But I do think that white folks need to work with white folks for a while and that people of color need to be with people of color, for just feeling purposes. There are some situations where, as a white person, I simply don’t belong. This is true whether or not I’m letting people of color take the lead and just sitting back or whatever. It makes me sad because I miss hearing all these viewpoints.

The issue of racism is really interesting, so when we start exploring this on the subtle layers … First, we have to get the overt layers out. We must stop what I consider to be the second round of lynching: unnecessary use of deadly force. They are absolutely unacceptable, and I think all communities have to come together to really put pressure on these things. But we all have to be a part of creating informal safety nets, too, and the way my mind works these days is: I’m not here to change the world as much as the world is here to change me.

A lot of times the foreground and the background flip for me, and I have to hold two things at once. Working in a police department as one of the first women and lesbians who came in—believe me, life was quite challenging in the 1980s. I saw a lot of things firsthand, so I made certain adaptations to my own discriminations. How can I live with my own freedom but not ignore oppression? With this practice, I found I can hold awareness of both freedom and oppression. I can wear my identities both as an authoritative police officer and as a woman and lesbian, minorities in my profession.

I want to wear my identities a little more loosely and, at the same time, to work for my own freedom and the freedom of all other people. I really, really believe that interdependence is so much of the mindfulness framework. I really believe that my personal liberation is dependent on yours. My thinking I am white inter-is with your thinking you are black.

There are two truths to hold all these things. How to live in the vastness of that white space, how to live with self-compassion, how to live in a way I understand that I am cause and not just effect, how to live from a basis of kindness to all beings. I ask myself now, with that ability to freeze the frame: Am I going to have a residue of regret about this action or these words? Because I have a lot of residues up for grabs.

I guess it’s part of the ethical framework, too. As a white person in this system, as somebody who had access to legal violence, it is a very interesting, challenging time for all of us in terms of how we support each other, how we create community. We have to come up with a different economic system that provides support for a lot more people than what we have now, and I don’t know how to change capitalism, quite frankly.

Cultivating Love and Compassion

I want to make one last plug for mindfulness. Something mindfulness has taught me that has been important for my individual and collective work is that things like love and compassion aren’t feelings as much as they’re abilities. They can be cultivated and nurtured. It’s not our fault in terms of wherever we are, but it is our responsibility. If you have some awareness about what is going on, you can also have some awareness of what can go on, whether it’s hope or love. We can learn ways to culture those abilities. They’re abilities rather than just feelings that come and go, both individually and collectively.

One thing my teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, talks about a lot is that we’re all both victims and oppressors, and we have to come to grips with this. Another thing I love that he talks about is not just having superiority and inferiority complexes but equality complexes, where we’re still comparing ourselves to each other. That’s connection.

In 2008 Cheri Maples was ordained a Dharma teacher by Thich Nhat Hanh. She worked for twenty-five years in the criminal justice system and was a police officer for 20 years, ending her career as the Captain of Personnel and Training for the Madison Police Department in Wisconsin. With Maureen Brady, she co-founded the Center for Mindfulness and Justice (mindfulnessandjustice.org). Interviews and articles by Cheri are available in the Mindfulness Bell’s online archive.