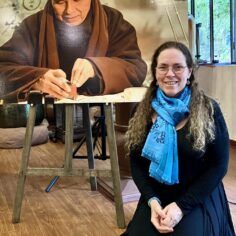

By Dr. Magda De La Paz Cabrero in March 2021

My biggest concern during the pandemic has been its impact on my eighty-seven-year-old mother, who lives in the American territory of Puerto Rico. The tropical island where I grew up has been severely affected by climate change, repeated earthquakes since December 2019, COVID-19, and government neglect. After Hurricane Maria three years ago,

By Dr. Magda De La Paz Cabrero in March 2021

My biggest concern during the pandemic has been its impact on my eighty-seven-year-old mother, who lives in the American territory of Puerto Rico. The tropical island where I grew up has been severely affected by climate change, repeated earthquakes since December 2019, COVID-19, and government neglect. After Hurricane Maria three years ago, hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans, including my mother’s last grandchild still residing in Puerto Rico, fled to the US mainland.

During a prolonged quarantine, my mother’s connection to the world consisted of television’s pessimistic messages, telephone conversations, and my sister’s company a few hours a week. While she has generally done well living independently, I was deeply worried that her response to multiple disasters in addition to her isolation at such a vulnerable age would take a toll on her. In the last week of June, I got on a flight to Puerto Rico from my home in the United States. While I was deeply worried about risking her life, for which I took extreme precautions, I knew I had no choice. “What is the worse risk, that my mother may become sick because of my visit or that she will be destroyed by her isolation?” I asked my alarmed friends.

Upon my arrival, I saw that my concerns were well founded. My mother had aged prematurely, and her physical and mental health had deteriorated. I quickly adopted my new role of nurturing my mother out of her suffering state and back into health, involving every resource I could think of—including my siblings’ collaboration. While my belief in interbeing had always guided my educational career and restorative justice advocacy, the time had come to implement it more intimately. I am convinced that without Thich Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness lessons and my Sangha’s support, all my training and professional experience would have not sufficed.

I also realized that I was immersed in a collective consciousness loaded with fear and despair. I needed a strong spiritual practice to prevent negative mental formations from controlling me. Thus, I called on what Thay describes as “the seed of mindfulness to manifest as a second energy in your mind’s consciousness in order to recognize, embrace, and calm the negative mental formation, so you can look deeply into the negativity to see its source.”

My daily practice consisted of at least one hour of sitting meditation in or outside my mother’s home and one hour of walking meditation outdoors while drinking Puerto Rican steaming coffee. I read some of Thay’s books, especially Silence: The Power of Quiet in a World Full of Noise, and listened to the mantra Namo Avalokiteshvara chant from my Plum Village app. I was grateful that my breathing exercises were readily available anytime my negative seeds were starting to sprout. I managed to remain mostly calm and uplifted. I made sure I always had an open space in my psyche for my mother’s needs. As Thay says, “Only when we have been able to open a space within ourselves, can we really help others.”

I also nourished myself through sense impressions by being mindful of Puerto Rico’s multi-colored lush vegetation, the hills covered in every shade of green and vibrant red and yellow trees bearing a variety of tropical fruit. I admired the colorful parakeets and parrots and paid close attention to the sounds they emitted.

I also listened to the usual morning sounds of the neighborhood, especially the animated conversations typical of a convivial society. I smelled and felt the touch of the humid breeze and the recurrent tropical rains. I smiled at the sun and moon as they illuminated my days and nights, as they rose and set through their daily cycles.

For my walking meditation, I strolled barefoot on the shores of the turquoise ocean and felt enchanted the day I spotted an iguana also strolling in the water next to me. I was grateful to the sea for receiving my suffering when I released it through my exhalations out to its salty warm waves, and for healing me as I inhaled the nurturing salty breeze it emanated. While the ocean was easily accessible to me when I was a child, my mindfulness practice now made it even more precious. Similarly, the park next to our home, overflowing with Maltese cross and bellflowers, filled me with the energy of an oasis.

“How can you sit the whole day doing nothing?” some people asked me. Well, thankfully, I live a rich inner life. Besides the literary interests that engage me, my mindfulness practice provides me with invaluable spiritual nourishment and healing. As Thich Nhat Hanh suggests, I took pleasure in spending time with my mother doing “things together in joyful noble silence.” I love the sound of silence. It is one of my favorite states. Avalokiteshvara, “the one who listens deeply to the sounds of the world,” inspired me daily.

In the book Silence, Thay wrote that if one can find silence within oneself, one can hear the sounds emitted by the Bodhisattva of Deep Listening. He named these sounds and described their distinct qualities. I meditated on the Sound of the One Who Observes the World, the sound of deep listening, which helped me to be vigilant of my mother’s and my own needs. The Brahma Sound, the transcendental sound om, I uttered during my hardest moments when no other practice helped me release my suffering. Moreover, the Sound That Transcends All Sounds of the World, the sound of impermanence, reminded me not to get too attached or caught up in the current difficulties. Every day I settled in the “deepest kind of silence,” which helped me make decisions and perceive experiences from the perspective of a deeper kind of truth, not of attachment or emotion.

I often marveled at the interbeing I sensed between my Zen teacher’s Vietnam and my own Puerto Rico during our respective ordeals. I also felt the connection between Thay and myself, as we were both back in our homelands after years of struggling to adapt to foreign ways of life. Paradoxically, spirituality originating far away from Puerto Rico helped me rediscover its immense beauty in a deeper way and understand a more profound truth that involves its inhabitants, not in their current state of despair, but in their fundamental beauty and resilience. I was also awed by the fact that Thay’s lessons on mindfulness and interbeing brought me closer to the person who brought me into the world. In our role reversal, I am now nurturing her.

In a Christian land in which the use of antidepressants has become commonplace, meditation and mindfulness are not widely practiced. People are generally expected to believe in a male God in the sky who, if prayed to, may remove obstacles or at least help us accept life’s misfortunes. With the pandemic, traditional worship practices are limited, especially for the elderly who, like my mother, are not used to virtual connections. While I respect other people’s forms of spirituality, I tell those close to me about how Thay’s teachings and my yearly pilgrimages to Plum Village have impacted me. Perhaps, to some, his teachings may shed light on ways to supplement their traditional practices or seek alternatives to medication.

Within a month, my mother started healing. I eventually managed to get her out of Puerto Rico to spend time with me during the nerve-wracking hurricane season. I believe my mother has realized that suffering in isolation for the sake of not burdening her family is unnecessarily dangerous.

As I look back on my experiences over these three months, they feel like a blessing defined by interbeing, loving kindness, and healing. I hope I will always feel satisfied that I did all I could to make my mother’s increasingly challenging life worth living, as comfortable and safe as possible, filled with companionship, connection, and loving kindness.

I now better appreciate how challenging supporting our elderly can be. For me it required understanding my own frailty, building inner strength and adaptability, and engaging in mindful practices that nourished me and helped me see deeper truths while remaining calm and positive. I had to open my heart to daily lessons on interbeing, nonduality, impermanence, detachment, and loving kindness. While detaching from my mother’s suffering and her physical presence in my life is undeniably daunting, I strive to accept my mother’s natural physical decline and to gain a deeper understanding of the nonduality of life and death. I am grateful that my ancestors are and will always be a part of me, especially my mother. As Thay, who feels as one with his mother, writes: “We are a community of cells, and all our ancestors are within us. We can hear their voices; we just need to listen.”