A Monument to Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

By Margaret Alexander

Alexei had always wanted to sculpt Dr. King’s face, so he was thrilled with the invitation. But he had never heard of Thich Nhat Hanh.

In the United States’ Deep South resides a testimonial to the strong bond between two great peacemakers—Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr.

A Monument to Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

By Margaret Alexander

Alexei had always wanted to sculpt Dr. King’s face, so he was thrilled with the invitation. But he had never heard of Thich Nhat Hanh.

In the United States’ Deep South resides a testimonial to the strong bond between two great peacemakers—Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. A life-sized sculpture of the two men was installed at Magnolia Grove Monastery in September 2015. The statue sparks curiosity among the monastery’s visitors: How did it come about? What is its connection to the monastery? Who was the sculptor, and how did he craft this prodigious work of art?

AN INVITATION

Alexei Kazantsev, the sculptor, has built statues throughout the world. One of his most notable creations is a group of fifteen large Buddhist pieces in a multi-acre bamboo forest owned by John Gulas in Mobile, Alabama. Alexei’s approach to those works was unusual. Instead of copying mass-produced representations of the Buddha, he learned from ancient images. Therefore he chose to model the sculptures after images of Apsaras (Buddhist angels) found in the tenth-century Byodo-in temple in Kyoto, Japan.

As word of this sculpture garden spread, monastics and other Buddhists were among the visitors coming to Mobile to see Alexei’s work. One of these visitors was Joan Dixon, a member of the Order of Interbeing and an artist herself. She lives in Mobile, and her Sangha meets in a shop owned by John Gulas.

Joan Dixon was contacted by Brother Michael, a monk at Magnolia Grove Monastery, asking if she knew someone who might compose a piece honoring Thay and Dr. King. She immediately thought of Alexei because his sculptures “are very powerful, with spiritual energy coming through.” 1 Joan showed photographs of Alexei’s art to the monastics. With the community’s support, in the summer of 2014, she invited him to meet with the monastics and make a proposal for what he might create.

Alexei had always wanted to sculpt Dr. King’s face, so he was thrilled with the invitation. But he had never heard of Thich Nhat Hanh. He began reading books and articles by and about Thay, and felt like he “was coming home.” 2 Not only does Thay write about universal truth, Alexei believes, but also he has found a “very simple way to say it.”

A SPIRITUAL CONNECTION

A native of Russia, Alexei feels that his upbringing in a communist society was part of his spiritual development. “The idea of communism,” he says, “is spiritual in nature—people give to society what they can, and receive from society what they need; however, communism has failed because people often take more than they need and give less than they can.” Raised in an environment where people shared a common vision, Alexei always felt attuned to life’s spiritual dimension. Additionally, he attributes his spiritual understanding to an early childhood experience. He developed “children’s arthritis” and couldn’t walk. In order for his bones to heal, he was required to lie flat, tied to a bed, from age seven to ten. He reflects how this led him to “always dwell in my inside world.”

Alexei spent twelve years training in realistic art in Russia. For Alexei, an artistic form—such as a sculpture—is a “vessel which contains the spirit.” His task is to become the “conduit” for this spirit. This process can be difficult, he says, likening it to climbing Mt. Everest. “There’s no promise that you’re going to reach that height.” Sometimes he has to endure uncertainty for multiple days, but “when I get into the creative space, it is like channeling the energy, or you connect to the collective conscious, or the divine.” After he’s made this connection, he can work inexhaustibly for eight to ten hours at a stretch.

When he arrived at Magnolia Grove and began to learn about the community, he felt he had “found a place in which people talked the same language, and we understood each other. Everybody I met in Magnolia is just incredible. You see people who see the real thing, to be in the present; everybody is awakened at the same time. I’ve never experienced that before.” He was happy to be in a community that lives in harmony, without discrimination. “I don’t divide people by race or nationality, good or bad; I divide them by lost and found. This is my philosophy on life,” Alexei says.

A Collaborative Process

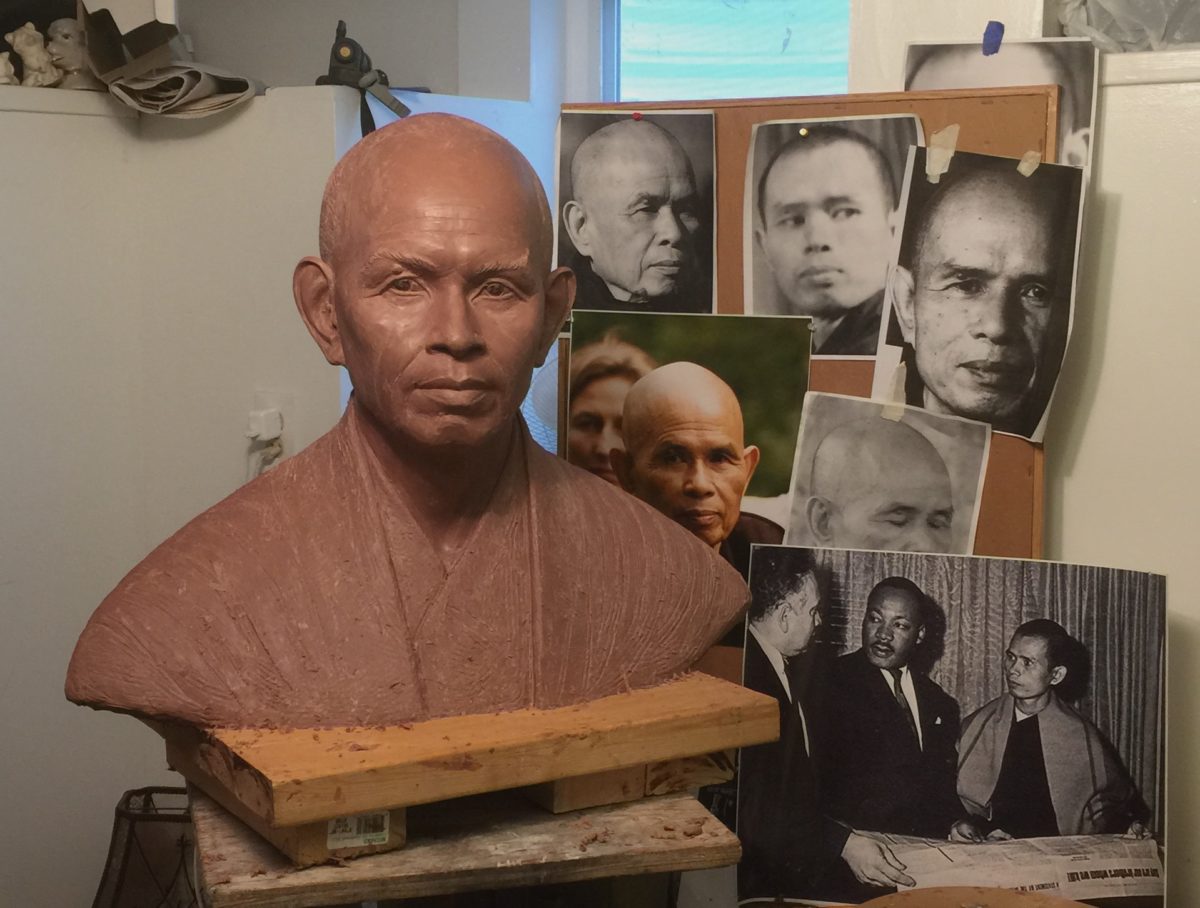

Describing the process of selecting a model photograph for the sculpture, Alexei says he sorted through hundreds of pictures provided by Thay’s community. Eventually, he, Joan Dixon, and members of the community chose a photograph of Thay and Dr. King standing together as they talked about peace at a Chicago press conference on June 1, 1966 (see p. 18). 3 Alexei spent a week at the monastery in September 2014, making drawings and creating a twelve-inch maquette, or preliminary model.

Once the initial design had been approved, Alexei started to work on the bodies of the two men in his studio in Colorado, where he lives with his wife and two sons. The project had a tight budget compared to previous commissions for bronze or marble sculptures, so he used a different process. First, he carved the bodies out of Styrofoam, and then selected a material called GFRC, or glass fiber reinforced concrete. This material, when applied in multiple layers, is so strong that it is used in building skyscrapers. The application of GFRC produced a stucco-like surface, out of which Alexei carved the two figures holding a newspaper between them.

Multiple people conferred about the wording on the newspaper. The title, “Beloved Community,” comes from Dr. King’s own words. The rest of the text is a distillation of Thay’s and Dr. King’s ideas: “To build a community that lives in harmony and awareness is the most noble task.”

Alexei returned to the monastery to compose the two men’s busts out of plastiline, a clay that stays moist longer than other materials. As Alexei began to create Thay’s head, he encountered an unexpected obstacle: Thay was in his forties when he met Dr. King, but if Alexei were to carve his face as he looked then, few people would recognize him.

Alexei forged forward. First, he sculpted Thay’s face as he appears in more recent pictures. Next, he changed Thay’s face to look younger. Finally, he asked Joan Dixon and Sister Dang Nghiem (Sister D) to help out—Joan for her artistic skills, and Sister D because she has known Thay for many years, and because as a physician, she has knowledge of anatomy. Alexei invited Sister D to help carve Thay’s face. He says, “When I sculpt, I am very open, because I don’t have what I call an ego. I’m always open to change and advice, and so it was a very collaborative process.”

The detailed construction of Thay’s bust took two months, while Dr. King’s took only ten days. Alexei attributes this difference to the fact that Dr. King’s face, which has become a cultural icon, was very familiar to him. Once the heads were mounted, the monastics requested that the statue be painted to look like bronze. Alexei created a coating that included bronze, metallic, and enamel paint. With the paint’s application and a coat of lacquer, the statue was done.

Now the sculpture needed a home. Some people wanted to place it near one of the monastery’s main buildings. Others thought it should be visible from the road, as a link to the community. Alexei believes all statuary should face toward a central focal point. The group’s solution was to place the statue close enough to the road that passersby could see it, while the figures face inward toward the monastery grounds. Alexei recalls that Sister Joy and Brother Phap Chung designed a meditation garden to accompany the statue. Two weeks before the installation, all of the monastics worked with a group of local Sangha members, whom Alexei calls the “Uncles Club,” to plant the garden and create a winding path edged with flowers.

MAGIC HAPPENED, LIGHTNING STRUCK

Alexei reflects on how the community at Magnolia Grove Monastery played an essential part in constructing this monument. He names Brother Michael, Brother Radiance, Sister D, Sister Joy, and Joan Dixon as taking key roles in all stages of the process. “I couldn’t have done it myself. Absolutely not. We all pulled together and boom! Magic happened, lightning struck.” Indeed, he considers this piece to be the “pinnacle of my artistic career.”

Thay’s presence in the project was invisible yet always there. Alexei explains that the sculpture was Thay’s idea, sparked by his love for Dr. King. Thay wanted a sculpture in this area of theUS, near where Dr. King did community organizing and worked for peace and justice during much of his life. “Thay was aware of the project’s progress,” Alexei shares. “When it was complete, he saw the image, smiled, and nodded his head. We got a blessing from Thay.”

In partnership with the fourfold Sangha, Alexei created more than a statue commemorating the relationship of two wise men who worked together for peace. The monument memorializes the spirit they recognized in each other and the unity of their message. As he worked on the statue, Alexei “tried to represent the oneness of Thay and Dr. King. However different they were, the black preacher and the Buddhist monk, as they came together, they crystallized their ideas and created this concept of a happy society. Dr. King is well known in our lives. Every little kid learns about him in school. His truth is abundant, like rain. Thay’s wisdom is like a little stream in the woods. You have to walk off of the beaten path to find it and satisfy your thirst for truth. In our lives, we need both of these forms of wisdom. These two men complement each other in the way they share the truth.”

1 Interview with Joan Dixon, February 3, 2016

2 Interview with Alexei Kazantsev, December 12, 2015

3 Thay describes this meeting in Together We Are One: Honoring Our Diversity, Celebrating Our Connection (Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 2010).

Margaret Alexander, True Autumn Lake (Chan Thu Tri), was ordained into the Order of Interbeing in 2011. Her passions are: volunteering for the Mindfulness Bell, facilitating community discussions about privilege/racial justice, and creating with fabric and beads. Margaret expresses much gratitude to Natascha Bruckner for her willingness to collaborate on every part of this article—from

conception to final touch!