By Margaret Kirschner

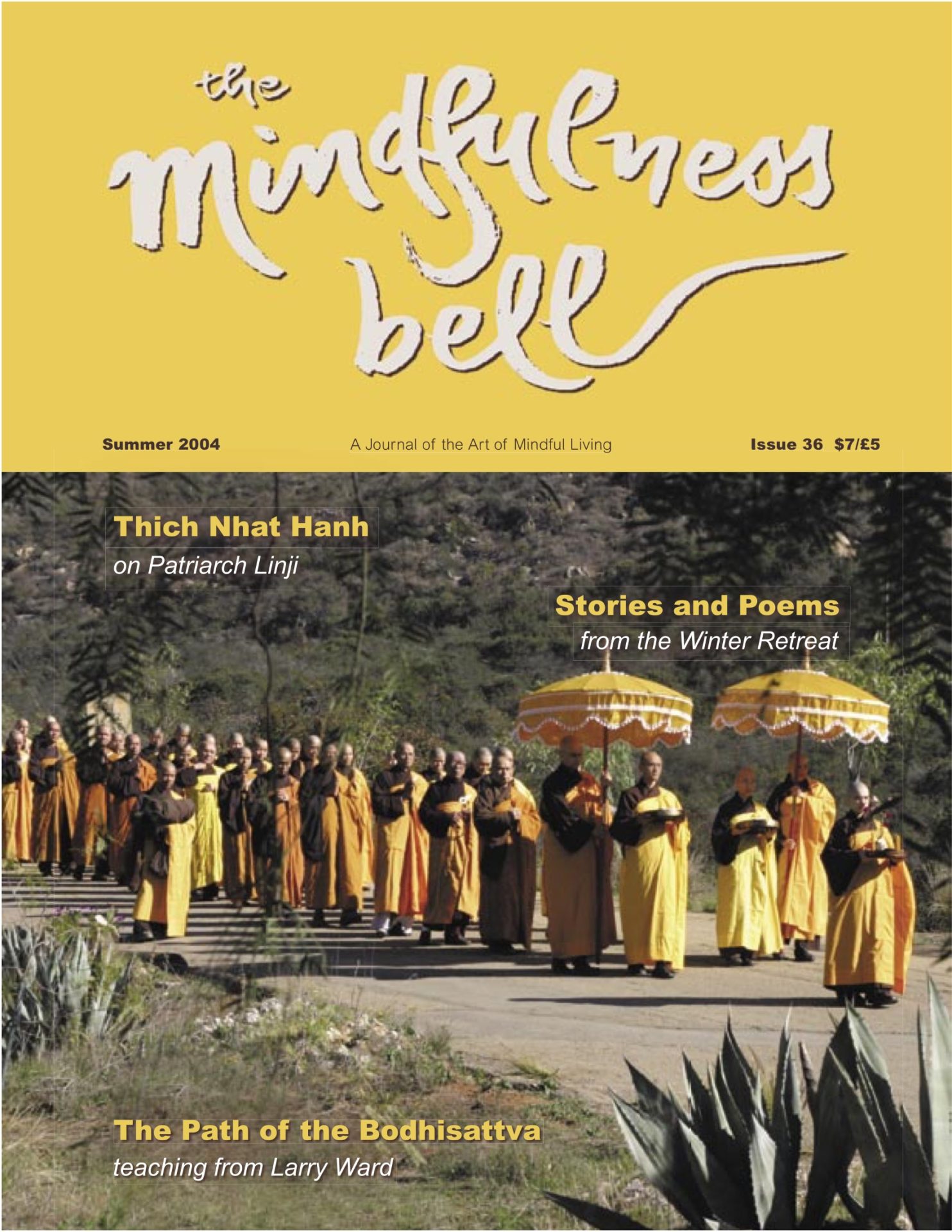

Visualize Deer Park during winter retreat. Imagine the logistics needed to accommodate 250 monastics and approximately 250 lay retreatants, up to 1,000 or so on Days of Mindfulness when the local community visits. Picture the kitchens that prepare the food, the dishes, pots, pans, and silverware that need to be washed after each meal. Estimate the number of showers, hand washings, toilet flushings, tooth brushing,

By Margaret Kirschner

Visualize Deer Park during winter retreat. Imagine the logistics needed to accommodate 250 monastics and approximately 250 lay retreatants, up to 1,000 or so on Days of Mindfulness when the local community visits. Picture the kitchens that prepare the food, the dishes, pots, pans, and silverware that need to be washed after each meal. Estimate the number of showers, hand washings, toilet flushings, tooth brushing, tea making, and the amount of water needed to keep the gardens alive and flourishing.

During the afternoon free time, a retreatant goes back to her room, ready to take a shower. She turns the faucet. Nothing happens. The water is off. She checks with neighbors. Theirs is off also. Next with the kitchen, and the restrooms near the Meditation Hall. Solidity Hamlet, Clarity Hamlet–all are without water. The pumps had stopped working. Was there panic? Was there grumbling and complaining? Was the water restored shortly thereafter? No, no, and no. The aridness of the desert enclosed the Deer Park retreatants.

Shortly after, the monastics announced a plan. They said the kitchens had reserve tanks that allowed enough water for meal preparations and cleanup. Large trucks would bring barrels of water, which would be placed outside our dormitories, along with buckets so we could bring in water to flush the toilets. We were asked to use the old slogan, “If it’s yellow, it’s mellow; if it’s brown, flush it down.” Packets of chlorinated wipes appeared here and there. Mindfulness practice continued as if nothing troublesome had occurred. The water did not come back on until the next day, at least eighteen hours later. But even when it returned, only one pump was working, so we were asked to continue to conserve as much as possible in the week to come.

What caused peace to pervade the difficulties created by this situation? Was it the calm manner of the monk who made the announcement that solicited the acceptance of the water shortage? Was it the mindfulness practice of the participants? Surely both contributed, but the initial meeting of the monastics who were charged with responsibility must have been a generating source. There had to have been a committee of calm thinking ones, with an awareness that nothing is permanent. There must have been trust in the skills of those who were to do the repairs and an understanding that creative solutions come from serene minds. I’d have loved to have been a mouse in the corner watching the mindfulness that contributed to everything working out so harmoniously.

And so it goes at our retreat, day by day. Each small activity, imbued with mindfulness, builds further mindfulness and takes us through life’s vexations with equanimity and joy. May we show our gratitude by remembering this experience and by sharing this accepting awareness with our families and communities.

Margaret Kirschner, True Silent Sound, lives in Portland, Oregon and practices with the Portland Community of Mindful Living. She was ordained into the Order of Interbeing during the winter retreat.