By Dr. Ashley Mack on

Dr. Ashley Mack shares how Thầy’s teachings bring freedom to the challenges of raising foster kids in a LGBTQIA+ family facing intergenerational trauma and depression.

Forty-Seven The present moment contains past and future. The secret of transformation is in the way we handle this very moment. Forty-Eight Transformation takes place in our daily life.

By Dr. Ashley Mack on

Dr. Ashley Mack shares how Thầy’s teachings bring freedom to the challenges of raising foster kids in a LGBTQIA+ family facing intergenerational trauma and depression.

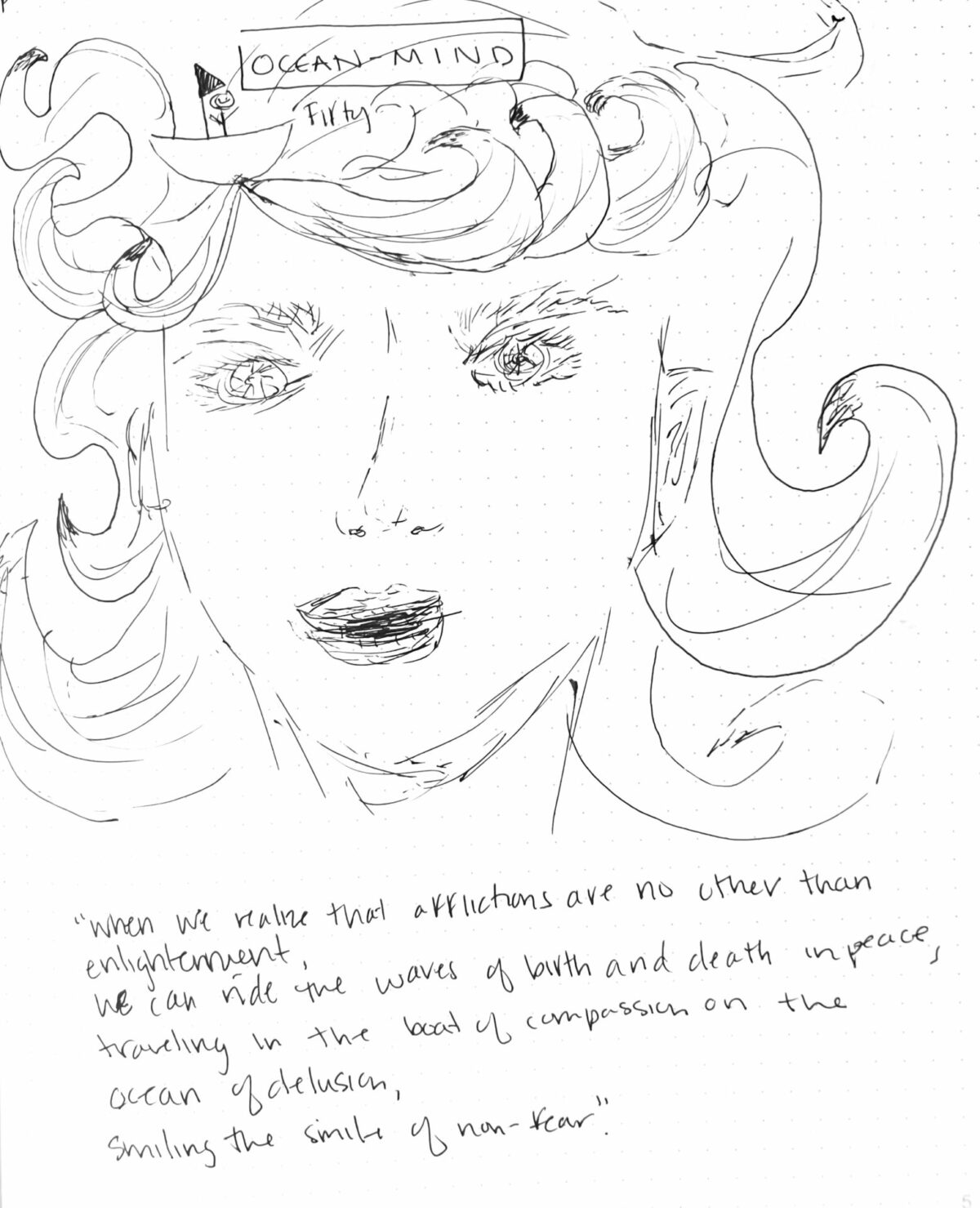

Forty-Seven The present moment contains past and future. The secret of transformation is in the way we handle this very moment. Forty-Eight Transformation takes place in our daily life. To make the work of transformation easy, practice with a Sangha. Forty-Nine Nothing is born, nothing dies. Nothing to hold on to, nothing to release. Samsara is nirvana. There is nothing to attain. Fifty When we realize that afflictions are no other than enlightenment, we can ride the waves of birth and death in peace, traveling in the boat of compassion on the ocean of delusion, smiling the smile of non-fear. From Fifty Verses on the Nature of Consciousness in Understanding Our Mind by Thích Nhất Hạnh

I have never met my children’s father, but Bryan—my partner—and I have been living in his wake since the kids came into our care in 2021. We decided to become foster parents because we wanted to serve our community. We heard of a lack of foster parents willing to give safe and affirming homes to LGBTQIA+ kids, and we knew we could offer a loving home where children could be themselves. We are both queer, and I am gender expansive. Bryan is in addiction recovery, and we have a lot of experience with trauma therapy. We felt prepared to take on the challenges that might arise when caring for kids who experienced trauma.

We were not expecting to adopt or become permanent caregivers. We figured we could be a temporary place for healing on the path to family reunification. But the first placement we received would be our last—three teenage (or soon to be teenage) siblings whose father had fled the country after an arrest warrant was issued for his acts of child abuse. Their mother had left several years before and was unresponsive to child service inquiries. On the first day they were with us, they asked us how we felt about gay pride. Bryan and I smiled and looked at each other. “We love it. We are both bisexual,” Bryan said. “And I am non-binary,” I followed up. They were gleeful. Everything felt right. We had just met, and we all expressed that we already felt like a family.

The time since then has been filled with immense, indescribable joy, but also much suffering. Abuse and trauma remain present in the body and mind long after they stop. I came to the Plum Village practice amidst this journey, and traveling this path has provided much solace amidst ongoing happiness and upheaval. I humbly offer bits of my story and practice in hopes that it might resonate or help someone else who is being pulled under while trying to stay on the path.

Intergenerational trauma, inter-are, and continuation

During my first visit to Magnolia Grove Monastery, I was taught how to touch the earth. I struggled with this practice of grounding and getting in touch with our ancestors. What about my father who abandoned me? Or my mother’s father who discarded her? Or the children’s mother who deserted them? The father who abused them and then fled? Why would I want to touch the earth to get in touch with them?

We are continuations of our ancestors, regardless of whether those relations brought us joy or pain in the past. I can touch the earth and be held by my late-Grandma Glad’s laughter and resilience during difficult times. I can also touch the earth and engage my awareness with intergenerational trauma that has been passed on. Even though we have never met the kid’s parents, we live in their wake. Just as they too drifted in the wake of their ancestors, and they in theirs before them. Even though the kid’s father is no longer in their lives, his actions and the fruits of that karma manifest in them alongside the genes he and their mother passed on to them.

Thầy notes in Understanding Our Mind that our minds are individual and collective. We are manifestations of our ancestors, experiences, parents, and society. In our family, Bryan and I come to this moment with the separate experiences we amassed before we met and partnered with each other, as well as with the separateness and collectiveness we have accumulated in our fifteen years of togetherness. When the kids joined our home, they too each brought with them the collection of their seeds of consciousness and habit energies. We are all wading in the wake of individual and collective manifestations of our ancestors, experiences, and culture. It is very easy to be pulled under by the unpredictable chaos and suffering that emerges in such a circumstance. We store images of our past pain. We develop habits and shortcuts to try to anticipate, stop, and avoid it. But when we do not take care of our feelings of suffering—instead trying to erase, trap, or ignore them—they can swallow us whole.

Caught in the current

In 2022—about eight months after the kids moved in—I entered a period of depression unlike any I had experienced in my adult life. Trauma’s wake caused mayhem as the kids’ suffering unfurled in their new circumstance. Cutting and self-harm. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Impulsive and dangerous sexual behavior. Psychiatric hospitalizations. Lying and manipulation. Anger and cruelty directed at themselves, each other, and us. A school fight and an expulsion. Even more disclosures of abuse. We tried to keep it together for them and to get them the professional therapeutic resources they needed to feel safe and to heal, but like a tsunami, the suffering just kept coming.

Even as we tried to cultivate a safe and happy environment, a cruel and toxic tongue inherited from their father found its expression in our home. “Dinner is ready ya’ll!” Bryan calls from the kitchen. “Get your a** in here or else!” one of them screams in a deep and bellowing voice as they make their way to the dinner table. They do this often—rephrasing our communication in an abusive and harmful way—as if to manifest their father in the present moment. He is gone, yet his uninvited ghost still sits at the dinner table with us. Like most teenagers, they do not shy away from telling us how horrible everything is, from dinner to our clothes to our personalities. More concerning is how much they relentlessly mock and criticize each other. When we point out that none of them like it when the others do this to them, and that the back-and-forth cruelty fosters even more and more of the same, they shrug and tell us, “This is who we are.” We know this is both true and not. They are manifestations of the past and capable of transformation in the present. We see moments of deep compassion, love, and kindness between them and us. But shaking the apparition of cruelty and its habitual energy has proved difficult.

During the required training to become a foster parent, they emphasize that kids from hard places really need love, attention, and stability so that they can form secure attachments with healthy caregivers. Yet we find that when we offer love to them, they often (not always) reject it. If we try to comfort them when they are suffering, they can (not always) lash out and recoil. This type of response is commonly referred to as “blocked trust.” Neglect, abuse, and abandonment in early childhood alters the brain and its neural pathways, which can produce an involuntary triggered fear response that blocks one’s ability to receive love, care, and affection. Even though they are now safe in our home, they do not fully trust that safety. We get along extremely well, yet their bodies and minds still manifest their past experiences. As we grow closer, they can experience the comfort and normality of our relationship as abnormal and uncomfortable. Bryan and I also, then, are affected by the individual and collective manifestations we swim in as a family.

I have tried my best to respond to their blocked trust with compassion and understanding. I told myself that I knew why they were responding this way. I had read all the books and completed the trainings. My own life experiences with an alcoholic and suicidal spouse and an absent father taught me that hurt people do hurtful things. I try to stay hopeful that eventually they will find comfort in our bond and home. But if I am honest, such hope was extremely hard to manifest during that first year. I found it difficult (as most would) to be ridiculed and rejected daily—even if I understood intellectually why they were saying what they were saying and doing what they were doing.

I was ashamed of my suffering and tried to suppress it. I did not understand why I took their actions to heart if I understood why it was happening. Eventually, I turned on myself and began disappearing into suffering. The joyful and confident parts of me retreated into the darkness. I wanted to die. I wanted to leave. I wanted to escape this life because the pain was too great. I was scared of the anger and sadness that I was experiencing. I felt like a failure. Maybe I was not made to be a parent? I began to avoid interactions with the kids because I felt like I was just harming them further. When I was not avoiding them, I was fixating on their behavior by trying to correct or control it. My anger and resentment flourished. I spoke with cruelty. I acted out of fear. I became addicted to video games. I was ashamed of how I felt and how I acted, towards them and myself. I retreated further and further into the darkness. “The problem is me and I should just die,” I thought. I wanted to be absolutely anywhere but the present moment because it felt too painful and overwhelming.

Now, resting safely on the other shore, I know I was experiencing a neurological phenomenon that psychologists call “blocked care.” Research published by the National Council on Adoption shows that foster and adoptive parents neurologically register repeated experiences of rejection the same way they register physical pain. This can lead to an involuntary reduction in compassion, withdrawal, and self-protection behaviors.

I was introduced to Thầy’s teachings just after his death in 2022 and in the midst of my depression. A YouTube video featuring Brother Pháp Dung first grabbed me from under the current and pulled me onto the ship deck. His willingness to talk about his depression as a monk and his bad habit energies helped me feel less broken and alone. I quickly consumed hundreds of hours of Dharma talks via YouTube. My partner bought me Thầy’s No Mud, No Lotus. I traveled to Magnolia Grove. Later, following the suggestion of Brother Action and Sister Tranquility, I brought my family there for a holiday retreat. The practice has led me to great insight about myself, provided me with a vocabulary to understand what was happening in my family, and offered a path of transformation.

Ocean mind

I’m not a seasoned nor perfect practitioner. I struggle every day to stay above the surface and remain committed to the practice as the reverberations of trauma linger around me, my perceptions continue to deceive me, and my habits lead me astray. Daily I remind myself to take refuge in my home that is here, now. Even now, though, I am fighting off thoughts of self-doubt and criticism that tell me I have nothing worth sharing with you here. Every time I think I’ve got it under control, I tend to find myself capsized and swirling in negative thoughts and judgements.

Sometimes it would be much easier to just let myself drown in it. We were notified recently that the oldest sibling—who left our home several months ago at her own request—went missing after running away from her new home. This news pulled me back under. I could feel the weight of my sadness, guilt, and regrets burying me alive. Somehow, I was able to find my breath amongst the snot and tears. I closed my eyes and imagined myself holding her (or was it me? Or both of us?) and rocking gently back and forth. I returned to the present moment—where Bryan and I still care for her siblings; where, despite the very real suffering, there are still sufficient conditions for joy, love, and transformation. Thankfully, she has since been found and is on her own path to healing.

I’m getting better at taking care of my suffering by cultivating seeds that stabilize my boat on this vast and unpredictable ocean. Acceptance and adaptation of our ocean mind is the wisdom that the practice nurtures. I can navigate rough seas with a smile of nonfear. When seeds of suffering (such as sadness, anger, fear, resentment, and guilt) rise in me, I try to acknowledge them and offer them space to express themselves without letting them direct me. Managing these seeds is not a perfect science—and I am certainly not perfect at it—but I try to greet my darkness with curiosity as I seek to understand it, rather than suppress or judge it. I look deeply at my suffering so that I can learn about and untangle myself from my habits, mental formations, and discernments.

Identifying what I am clinging to grounds me. I ask myself: What am I grasping at/for? How is this grasping a manifestation of deep fears of abandonment and rejection? My habit energies (as a child of a single parent, a partner to an alcoholic who experiences suicidal ideation, and as a parent to children who deeply suffer/ed) maturated out of real fears of losing the people I love and facing difficult circumstances. The uncertain chaos of these experiences habituated me to be a fixer and to seek out fixing as a means of stabilizing situations and receiving love. But what was a functional coping mechanism in response to difficult times is also a maladaptive habit energy that can cause more suffering. I wonder: What am I desperately, feverishly holding on to in this moment that is keeping me from dwelling peacefully here?

I also actively cultivate seeds of joy, compassion, and love to secure stability for myself and my family in the present moment amidst tumult. Of course, I sit for meditation daily, listen to guided meditations, eat mindfully, and try to carve out time each day to walk with full presence. The kids sometimes join Bryan and I to stop for the mindfulness bell that rings each half hour from the Plum Village app on my cell phone (when they are not making fun of us for it, of course). But I’ve learned that my practice does not always look like it does on retreats. I also put on Harry Styles and clean the house while dancing. I bake cupcakes and make art with the kids. I delight in watching them realize what they can create. I listen deeply to their curious musings and relentless questions, which always keep me on my toes. I spend time with myself outside, admiring the leaning eighty-year-old water oak tree in our backyard. During fall, its enormous branches rain acorns and leaves on our outdoor patio. I observe in amusement each acorn that drops, hits the wooden porch, and bounces to the ground. I try not to think about the fact that I’ll have to clean it up later. I revere Bryan when he cracks a joke and the kids burst out in laughter. I savor these moments as they happen. I am grateful that I am here in this moment to fully enjoy them.

The other day, I was scrolling through Instagram and a video of Thầy appeared. He knowingly explains: “Like a wave on the surface of the ocean, she may be very fearful because she gets caught in notions like beginning, ending, going up, going down, more or less beautiful than the other waves. But if the wave is aware that she is water, then she loses all this kind of fear. Going up, she is joyful; going down, she is joyful. Because she knows that she is water. She’s not only a wave, she’s also water. So, water represents the Ultimate. Water represents God. Water represents Nirvana.”

A strong mindfulness seed, built through daily practice, helps me smile the smile of nonfear in this (still leaky) boat of compassion on this ocean of delusion. As this seed ripens, trauma’s wakes overtake me less and less. Mindfulness is a passive type of habitual action—a cultivated sturdiness. Breathing in, I am a wave. Breathing out, I am also water. I lean back and let go, allowing myself to dance with the other waves and be with the water. Breathing in, I smile going up. Breathing out, I smile going down. I know I will have to maneuver and be responsive as life continues to surprise me, but my habitual need to control, fix, or fight my circumstances is dimmed. The Dharma, Sangha, and Buddha remind me that I am also water. Oh, beloved community! I am so grateful for this insight, for every day it is keeping me afloat.