By Cheri Maples

Cheri Maples offered this Dharma talk at the 21-Day Retreat: Vulture Peak Gathering on June 15, 2016, in New Hamlet, Plum Village.

Dear Thay, dear beloved community, it’s so wonderful to be here with you.

I was a police officer seven years into my career when I ended up at my first retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay).

By Cheri Maples

Cheri Maples offered this Dharma talk at the 21-Day Retreat: Vulture Peak Gathering on June 15, 2016, in New Hamlet, Plum Village.

Dear Thay, dear beloved community, it’s so wonderful to be here with you.

I was a police officer seven years into my career when I ended up at my first retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay). I had already noticed that with many police officers, three things start to happen over the course of their career and that had already happened to me.

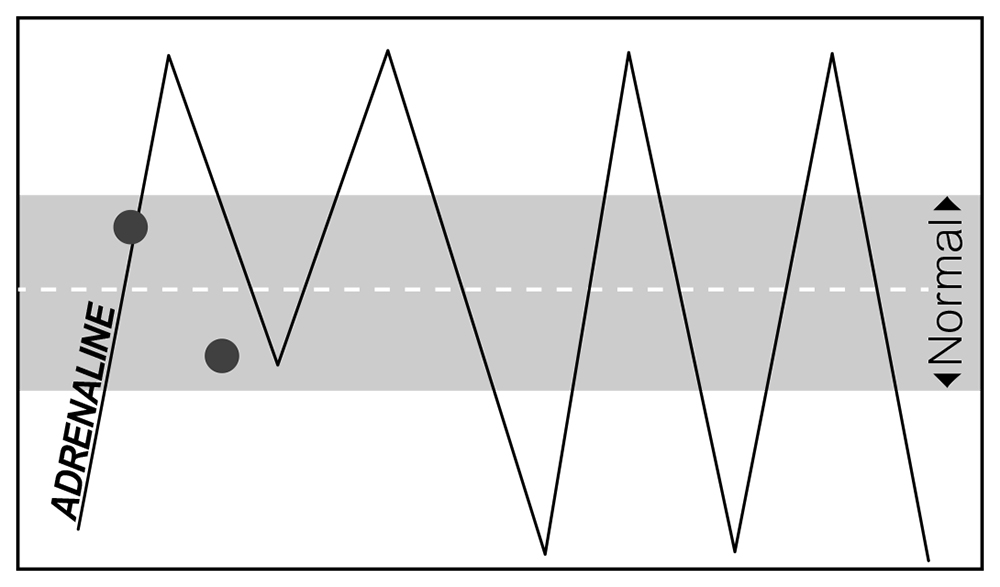

Physiologically, many of you might be able to relate to this if you live very busy lives, multi-tasking and doing too much. Research has shown that we all have a certain amount of adrenaline. People who know how to be rather than do are probably in the normal range. What happens with police officers, and you can probably relate to this, is that adrenaline starts to shoot up because of hypervigilance—being worried about your own safety and the safety of everybody else. We’re always taught about what can go wrong—not so much about what can go right, which is the majority of the time. The adrenaline shoots out of the normal range and peaks, then takes twenty-four hours to come back to normal, but people go back to work before that twenty-four hours is up. So adrenaline starts going up and down, above and below the normal range.

When the adrenaline kicks in, people are fast on their feet, able to make command decisions, and they have a sense of humor. And then when they are at home, the adrenaline drops way down and this looks like no energy, listlessness, depression. There are usually four times as many police officers, in the US, who take their own lives as are killed in the line of duty. This is a very real phenomenon.

Emotionally, what begins to happen is the effects manifest as irritation and impatience and anger and depression. There’s a very cynical sort of response that develops. Spiritually, the effects of doing the job manifest as an armoring and numbing of the heart. It’s very hard to be compassionate when those things are going on.

The other thing that happens is you develop what is known as the “I used to” syndrome:

I used to know how to water the seeds of joy.

I used to bike.

I used to play sports.

I used to garden.

I used to write poetry.

I used to have hobbies.

All those things are gone, and your world becomes smaller and smaller because of shift work and odd hours. Thinking that people don’t understand, you end up socializing only with other police officers, so all those things get reinforced.

That’s how I showed up at my very first retreat with Thay in 1991. I came very armored and defended. I was ready for people to hate me because I was a police officer. That happens a lot, even among people whose progressive politics they share. They’d see the uniform and immediately make a decision about who I was. That’s the attitude I came there with, and what happened? I have to show it. [Cheri draws a red dot on the white board.] What do you see there? A red dot. That’s where I was living. Meditation and mindfulness help you see the white space. [She draws red dots in the white space.] Here we are with all this spaciousness available to us, and we hang on so tight to our little red dots: our thoughts and our emotions.

Out here, love is available, happiness is available. No coming, no going is available, the spaciousness of being everything and nothing at the same time. Even after that first retreat, I started to understand some of that intuitively. All I wanted to do was practice. I began to think of meditation as just resting my mind in open awareness, and at that retreat I touched peace in a really fabulous way.

TRANSFORMATION ON THE JOB

Many strange things happened after that retreat. I was working nights as a sergeant. I was going on calls and I couldn’t understand why everybody around me had changed. They seemed to have gotten kinder in my absence, even people I was arresting! [Laughter] It didn’t make any sense to me. I didn’t know if somebody had gone around and sprayed Prozac or some other antidepressant while I was gone, but it took me a little while to see that it was my energy that was different, and people were responding to it. That was an incredible teaching for me because there it was, the proof in the pudding.

At that retreat, the Five Mindfulness Trainings came up, and of course the first one is Reverence for Life. I said, “I can’t take these, I carry a gun for a living, and I never know what’s going to happen.” To this day I can’t remember if it was Thay or Sister Chan Khong who said to me, “Who else would we want to carry a gun except somebody who will do it mindfully?” (Laughter) It was a whole new way to look at things!

The changes were incremental, but I stopped doing my job in a mechanical way. What I started to see is what was right in front of me, which I seemed to have missed with the other attitude: a suffering human being who needed my help and often didn’t have any place else to turn. So I started taking my time on the calls I went on. I started trying to connect with people from a different space.

One of my favorite stories is an experience of going on a domestic violence call. We had a mandatory arrest policy in those days, so if anybody was threatening somebody in a physical way, you were supposed to arrest them. I went on this call, and I didn’t have any backup, and a woman came running out and said, “My husband has my child and I’m really scared. We just broke up, and he won’t let her out to come be with me. I’m picking her up. We have an agreement about who is supposed to have the child when, and now it’s my turn.”

I asked her to go wait in the car down the block, and I knocked on the door. I’m about five feet three inches, and this six-foot-four-inch man who looked very angry opened the door. I could just see the suffering. It was so obvious to me. In a very calm voice, I said, “May I come in? I’m just here to listen and to help.” I came in and saw his daughter, and I said, “You know what, I see your little girl over here, and I know you love her, and I know how much you care about her, and I see that she’s scared, and I know you don’t want that to happen. So how about if we let her go out and be with her mother, and you and I talk.” And he did.

Rather than escalating this situation to the point where an arrest had to be made, it was just a matter of being compassionate and mindful. I violated every policy in the book, and with my gun belt and my bulletproof vest I sat down next to this guy on the couch, which you’re never supposed to do. And he started crying in my arms. That was an incredible experience for me in terms of what a little kindness and compassion can do, and that there are alternative ways to respond to people. Of course when you’re angry, irritated, and cynical yourself, it’s really hard to see those possibilities.

I ran into this man three days later. I was walking down the street that I lived on and he came up behind me—you know, it’s not good to come up behind a police officer. [Laughter] He picked me up off the ground and he said, “You! You! You saved my life that night.” It was a wonderful experience.

TWO KEY TEACHINGS

So I emphasized two of the teachings of Thay and the Order of Interbeing. There’s an emphasis on community. There’s also an emphasis, not only on happiness in the present moment and having a foundational mindfulness practice, but building community and engaged practice.

Those two things, building community (Sangha) and engaged practice, are not found in too many other Buddhist traditions. Those two things are just so special. I started thinking of Sangha as community. I joined a Sangha right after that retreat, but I started thinking of community as wherever I was. I started thinking of my workplace as a Sangha; I started thinking of my family as a Sangha.

In 2002, I came to Plum Village. Eleven years had passed and I became a member of the Order of Interbeing. Thay transmitted the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings to me and thirty-two other people when I was here for the twenty-one-day retreat.

In those days you wrote a letter to Thay. You still write a letter if you want to be ordained. I didn’t think that he read these letters, but I put it in the bell [in the meditation hall]. My letter was about how I was still struggling with feeling like both the victim and oppressor in this job, bouncing back and forth between those. The next day Thay gave a Dharma talk on the different faces of love. I was sitting in the back, and he mentioned police officers. I had tears streaming down my face. Another big transition took place, more softness, more understanding of Thay’s teaching that we’re all victims and oppressors.

A RETREAT FOR POLICE OFFICERS

One of the ripple effects of this happened when we were doing working meditation and chopping vegetables. I said to the woman next to me, “I have this very ridiculous image in my head of police officers holding hands and doing walking meditation together, creating peaceful steps on the earth.” She looked at me and she said, “Cheri, you can make that happen!” Thursday there was a question-and-answer session, and I got up and asked Thay if he would come do a retreat for police officers. I was very worried about what the response would be, and much to my delight he looked up and said, “Yes, I think we do it next year.” [Laughter]

There was a year to organize things and try to get police officers to come to a mindfulness retreat with a Buddhist teacher. It was very, very hard. There was a big reaction. I started getting hate e-mails. The separation of church and state, even though it was going to be a nonsectarian retreat, came up and it was very challenging. But I had wonderful people in my own Sangha and had contacted people among the monastics. That helped a lot.

So Thay came and we made this happen. I don’t remember how many people there were. About sixteen officers from my own police department were there. Thay’s first Dharma talk included a statement about how you cannot fight violence with violence. If you use violence, you are going to get violence in return. After that first talk, the police officers surrounded me and said, “Cheri, what are we supposed to do? What do you mean, you can’t fight violence with violence? What does he mean by that? We want to talk to him.” [Laughter] And I said, “Well, I’ve never had a personal talk myself with Thich Nhat Hanh, but I will see what I can do.” Eventually Thay came and talked to just the police officers, and by the end of the hour that he spent with them, the whole room grew calm. It was just so beautiful, and after that there was never another problem or objection that entire week.

One of the things that affected me was that at the end of the retreat, Thay said, “Are we going to hear from the police officers?” The night before the retreat ended, the police officers gave a presentation. I have never heard police officers share like that, share what life is like for them as a police officer, and never before have I seen a community be so receptive to what they had to say. I could just see them lighting up; it was so meaningful that there were people who were willing to be receptive to this. At the end of that retreat, the officers from my department and I held hands and did walking meditation. You never know what the ripple effects of anything can be!

TRANSMISSION OF THE LAMP

Then all kinds of things happened once I got back to Madison out on the street. This is a story that I just love: one of the people who was at the retreat came up to me and said, “Cheri, I just saw two of your young officers who were at the retreat. They were arresting somebody, and they recognized me. They arrested the person, and they put him in the back of the car, and then they turned to me and they bowed.” (Laughter) I said, “Well, when we bow to the person that we’re arresting as well as to the community that we’re doing it for, we will really have arrived.”

Then in 2007, I went to Vietnam along with a big group of Westerners with Thay and the monastic community. That had a big impact on me. Toward the end of that, Sister Chan Khong delivered the message to me that Thay wanted to make me a Dharma teacher and to transmit the lamp to me. So in 2008 the transmission of the lamp happened. This is my gatha for Thay that I’d like to share with you:

Breathing in, I know that mindfulness is the path to peace.

Breathing out, I know that peace is the path to mindfulness.

Breathing in, I know that peace is the path to justice.

Breathing out, I know that justice is the path to peace.

Breathing in, I know my duty is to provide safety and protection to all beings.

Breathing out, I am humbled and honored by my duty as a peace officer.

Breathing in, I choose mindfulness as my armor and compassion as my weapon.

Breathing out, I aspire to bring love and understanding to all I serve.

Cornell West, an African-American man in the United States, said the epitome of how I think we should view policing: “Justice is what love looks like in public.” How different would our system look if we adopted this definition of justice as the foundation for our whole system? It would just be incredible.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MINDFULNESS

There are three interrelated areas in my own personal work over the course of the years where the practice got deeper and deeper for me. The first was my own inner work, my meditation and mindfulness practice, which is of course the foundation for everything; the second area was relationships; and the third area was engaged practice.

The Buddha was so good at providing the architecture for our distress and also the architecture for our liberation. Thay was so wonderful at conveying the Buddhist teachings in a simple way that could be understood. One of the things that happened for me is what Thay describes as the psychology of mindfulness. In the psychology of mindfulness, there are two things that we are asked to be. One is a good curator of the museum of our past, and the other is a good gardener of our store consciousness. If we’re a good curator of the museum of our past, we can reframe our past, we can understand it in the service of our own freedom. However, if we carry it too far, we get attached to the wounded self, because then we’re constantly taking bus tickets back to our past.

We’re also learning how to be a good gardener. We’re learning what to incline our mind toward, how to water the seeds of joy and kindness and understanding and compassion. But in order to be able to do this, we have to understand how our experience is born moment to moment. If we can start to watch what arises and notice how our experience is born moment to moment, we can make conscious decisions about how to incline the heart and mind. And that is probably the most powerful thing that has happened to me over the years of this practice.

I can’t tell you how many people come up to me and say: “Cheri, you’ve gotten so much softer.” And I guess it’s true! Those protective layerings of armor are removed one at a time.

You learn about craving and aversion and how to work with both of them. A very subtle form of craving that I noticed was the craving to become. Unfortunately, in our society, success often gets equated with doing. One thing Thay has helped me understand is that the quality of your doing will always be dependent on the quality of your being. This requires a certain discipline, in that you cannot let the things that matter the most be at the mercy of the things that matter the least. So often we think, if I just get this done, and this done and this done, then I’ll focus on my practice. We become habitual “waiters.” We become addicted to doing. As a result, in my culture anyway, we have many people who are tired and wired, which leads to a lot of contentious behavior.

Understanding is key to this practice. I want to tell you a little story that, when I think back on it, makes me smile so much. It was my first week of being a rookie police officer on the street. We had just come off all of our experiences with our field training officers, and we were now riding alone. We have these briefing sessions before every shift starts. One of the first things that happened to me is the lieutenant of my shift said to me, “Maples, there’s a homeless guy down there in the basement, where our squad cars are and where our evidence room is. I want you to go down there and get him out of there and skip briefing to do it.” I go down there and I make contact with this man, who proceeds to tell me he doesn’t have to go anywhere because he’s the president of the United States. (Laughter) Rather than understanding him and trying to put myself in his position, I argue with him that he’s not the president of the United States. I’m getting more and more nervous because I know all these veteran police officers are going to be coming down the stairs, and I’m failing at my very first assignment. So this is not going well.

Finally, one of the veteran officers walked down. He said, “Hey, rookie, let me show you how it’s done.” He went and he got a key to the squad car closest to where this homeless man was standing. He opened the back door and said, “Mr. President, your limo awaits you.” [Laughter] The guy got right in and off they went. So that taught me something about working for social change.

One of the things that I think is really important is that we have to learn the difference between self-esteem and self-compassion, because until we learn how to bring true self-compassion to ourselves, the practice doesn’t really work well with other people. You can make a full time job out of self-improvement, which leads to high self-esteem, and I guess that’s better than low self-esteem. But the problem with high self-esteem is you’re still comparing yourself to other people. In fact, sometimes you’re competing with them and secretly hoping they do worse than you do. It’s not a very good way to live a spiritual life.

With self-compassion, we’re learning how to bring not just empathy to ourselves but goodwill to ourselves, in a phenomenal way. When I’m able to do that with the tools in the practice, the volume of “me” goes way down. I’m happiest when the volume of “me” is lowest. When the volume of “me” goes up, all those habit seeds are ready to spring into action.

Thomas Merton said this, and to me it is the epitome of Thay’s teachings: “To allow ourselves to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone and everything, is to succumb to violence. The frenzy of our activism neutralizes our work for peace; it destroys our own inner capacity for peace; it destroys the fruitfulness of our own work because it kills the root of inner wisdom, which makes work fruitful.”

We have prison projects in Wisconsin now, which went from being in one prison to being in many prisons. I’m happy to say that we are about to start teaching mindfulness to the guards. With all the scientific research that’s out there on mindfulness now, they are asking us to bring it, not just to the correctional officers but to probation and parole agents as well. That is huge.

It’s so important to keep the energy of our practice alive; that’s why we have sixty days of mindfulness a year as members of the Order of Interbeing. Have any of you heard of compassion fatigue, burnout? To me, burnout is a sign that we’re violating our own nature in some way. It’s usually regarded as a result of trying to give too much, but I think it could result from trying to give what we don’t have, and this is the ultimate in giving too little. I think that’s where compassion fatigue comes from. So when the gift that we give is an integral and valued part of our own journey, when it comes from the organic reality of inner work, it’s going to renew itself and be limitless in nature. But that means we have to keep our practice very strong and very alive.

RELATIONSHIP AS A SPIRITUAL PRACTICE

To me, relationships are the litmus test of spirituality. If our practice doesn’t show up in our relationships then something is wrong. From a practice perspective, this is probably the single most important thing. As a cop who carried a gun on a daily basis, I started to experience the incredible healing power of non-aggression. What I learned to bring to any interaction was the intention not to cause more harm, and that included those times when I had to use force.

One of the other things that Thay taught me that was so valuable is that compassion can be gentle and compassion can be fierce. Wisdom is knowing when to employ the gentle compassion of understanding or the fierce compassion of good boundaries. How we talk and relate to others is probably the most important peace work that we can engage in.

At work when I was captain of personnel and training, I was in charge of training the whole department, so I could get some really good things done. I remember sitting at my computer, working on the curriculum for the Leadership Academy, when one of my young officers came in and said, “Captain, can I please talk to you?” Internally I went, “Argh!” because I didn’t want to interrupt what was happening; I had to get this done. That was such a lesson to me. I immediately recognized what was happening and made a commitment that I was going to switch the foreground and the background. Relationships were going to be more important to me than tasks. That meant managing a to-do list. It meant some people would be upset because I didn’t get as many things done as I did before. But what could be more important than giving my presence to another human being? The ripple effects of that, you can never know.

REFORMING THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

I want to talk to you about the current criminal justice system and what I think needs to change. I can’t speak for what’s going on in other countries, but I can speak about what’s going on in the United States. Our current criminal justice system is based on a very faulty premise: the premise that the punishment of the perpetrator is going to heal the victim and rehabilitate the perpetrator.

What I found is that neither of those things are true. It seems to reflect a collective belief that contributes to all kinds of interpersonal and systemic dysfunction. What this premise fails to recognize is one of the basic premises of restorative justice: it’s not the wrongdoer’s repentance that creates forgiveness; it’s the victim’s forgiveness that creates repentance. I’ve seen this happen over and over again. So what do we have to do to change the criminal justice system? I’ve been focusing on five things.

1. Teach mindfulness

We need to recognize the costs of working as a police officer. If you take soldiers or people that are on SWAT teams, or the ops-teams in policing, the effects that I talked about are much more intense. We teach them how to keep themselves and others physically safe by using force, and how to use force. But we don’t teach them how to keep themselves emotionally safe. That’s where I have received such a gift from Thay, the gift of mindfulness.

It’s important that we begin to provide criminal justice professionals with the training that will help them identify how their world works, especially in the emotional realm. It’s important that we not just do stress reduction. The thing about mindfulness, and we know this from the mindfulness trainings, is that it brings a whole ethical framework along with it. What I can do, as a fellow police officer, is translate that language into language they understand. I don’t talk to them about Buddhism. I know the language, I know the culture, and all of you know this same thing wherever you are; we have to figure out how to translate it. So focusing on the emotional health of criminal justice professionals is very important.

2. Recognize biases in decision-making

The second thing is that we need to take seriously the conscious and unconscious biases that police officers and other criminal justice professionals carry that leads to racial profiling and the incredible racial disparities throughout our system. These unconscious biases show up, not just in the obvious ways of deadly force, but they also show up with coworkers and people we interact with. This builds resentments and fuels divisions and threatens our own safety as well as the safety of others.

With respect to racial disparities, I think police officers can be trained to slow down the decision-making process. I used to watch young officers stop a car, and I would say to them, “Okay, I want you to talk me through the reasons you made that stop and what was going on. And now I want you to talk me through where your reasonable suspicion was for having them get out of the car and for searching the car. I want you to talk me through the thought process that happened.” There usually is an opportunity for me to make a difference.

There are decision-making points in any organization that can be identified where race can be a factor. It’s important that every single one of us identifies those decision-making points in our own organizations. With respect to discrimination and oppression in our collective lives, activists face many challenges. For those of us who have experienced marginalization of some kind, how do we free ourselves from the adaptations that we’ve made to our oppression? For those of us who have unearthed the unearned assets of privileges, how do we cut through the sense of privilege in some areas of life and our inferior status in others? How do we get over our superiority, inferiority, and equality complexes?

3. Build the capacity of neighborhoods

The third thing that has to happen is coordinated community responses. We have to start taking seriously the proposition that public safety depends on the capacity of neighborhoods. In terms of engaged Buddhism, we’ve come up with several different ways to build the capacity of neighborhoods, and I hope I get a chance to do a Q&A session at some point and tell you about those.

4. Rely on coordinated community responses

The fourth strategy is that we need to put a lot more effort into reducing environmental opportunities for crime. We could gather more data to notice what the patterns are, be proactive rather than reactive so that we don’t keep responding to the same thing over and over. Rather than having officers tied to radio calls—“go here, go there”—they would be more connected to neighborhoods and technology and crime prevention resources. Police officers have to understand that in order to be effective, they can’t rely on their authority. They have to rely on so much more, a much larger coordinated community effort.

5. Be wary of militarization

A fifth thing I want to address is that we should all be very, very concerned about the militarization of our police departments. The police mission is very different—to serve and protect our neighbors, our friends, our community residents. We don’t do that by militarizing our departments and turning people into enemies. I think that’s where communities really matter, because it’s pressure on police departments to change that makes all the difference.

The last thing I would say is that police officers need your support. They need your understanding. I’ve seen what happens when they get it. They need to hear from you, they need to understand you. We need to put police officers and residents of communities into situations where they have the opportunity for dialogue. I think that makes all the difference in the world.

THE MOST RADICAL POLITICAL ACT

One of the things that I committed to, as a result of my own engaged Buddhism, is noticing the unwritten and unconscious agreements that exist in the organization, in the culture of policing. Those things aren’t in the policy manual.

The things we get socialized to in any community can be identified. Once you bring them into the conscious arena for discussion, more ethical behaviors start to happen just because people are examining and thinking about those behaviors. So often in the organizations and communities we’re part of, we tend to think of ourselves as effect rather than cause. We seem to believe that someone or something else is the problem, and that someone needs to do something better for things to change. We forget that we’re a member of this organization! People come out of a meeting and say, “Oh, that was a terrible meeting.” And I say, “Were you there? It was a terrible meeting because we all made it a terrible meeting. What could you have done to improve it?” In authentic community membership, we’re always holding ourselves accountable for the well-being of the larger community. We become more than just judging critics and consumers, and we start to believe that this world, this organization, this meeting, this gathering, is ours to construct together.

You can be the person who makes the difference in a contentious interaction; you can be the person who, because of your practice, pauses and refrains; you can be the person who, rather than exacerbating pain and violence, transforms it by the way you bear witness to it; you can be the person who, instead of telling people how it should be, brings those unconscious and unskillful ways into the conscious arena of dialogue; you can be the person who chooses not to gossip or to recruit others to your viewpoint behind closed doors in an organization.

Probably the most radical political act that any of us will engage in is to learn to live in more harmony with everyone and everything. To change the world or to love everybody is too big an ambition for any single person, but to respond to this moment with engagement and compassion is possible for each and every one of us. What Thich Nhat Hanh inspired in me was a strong belief that even something like carrying a gun for a living can be an act of love, if one is also armed with mindfulness and a compassionate intention.

Thank you for your presence, your practice, and your attention.

Edited by Janelle Combelic

Cheri Maples is a Dharma teacher, keynote speaker, and organizational consultant and trainer. In 2008 she was ordained a Dharma teacher by Thich Nhat Hanh, her long-time spiritual teacher. She worked for twenty-five years in the criminal justice system. She was a police officer for 20 years, ending her career as the Captain of Personnel and Training for the Madison Police Department. With Maureen Brady, she co-founded the Center for Mindfulness and Justice (mindfulnessandjustice.org).