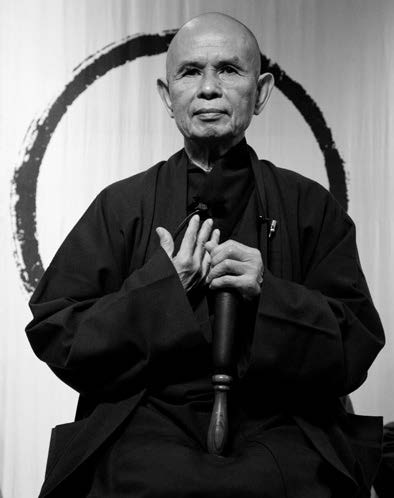

By Thich Nhat Hanh

November 25, 2004

Thanksgiving Day

Lower Hamlet, Plum Village

Good morning, dear Sangha. Today is the 25th of November in the year 2004, and we are in the Lower Hamlet during our Fall Retreat.

This morning we spoke about a telephone line that should be called the “compassionate line.” We hope that line should be established everywhere so that the young people in their despair,

By Thich Nhat Hanh

November 25, 2004

Thanksgiving Day

Lower Hamlet, Plum Village

Good morning, dear Sangha. Today is the 25th of November in the year 2004, and we are in the Lower Hamlet during our Fall Retreat.

This morning we spoke about a telephone line that should be called the “compassionate line.” We hope that line should be established everywhere so that the young people in their despair, in their suffering, in their strong emotions, may have a chance to talk to someone who could understand them. We learned that the number of young people who commit suicide every day is very alarming. Thirty-three of them every day in France is a lot, and we should do something in order to avoid that kind of damage. The young people feel lonely, they feel cut off even from their parents, and when they have a strong emotion, they suffer so much, they don’t know how to handle the suffering. They may think that the only way to stop suffering is to go and kill themselves.

The compassionate line should be there for them in the moment of despair, of utmost suffering; they should be able to talk to someone. And who is that someone? A psychotherapist, a doctor, a teacher, or someone who has the capacity of listening. Who is that one who is ready to listen to them? Each of us has to make a vow to become that person.

In the Buddhist tradition, we speak of a person who has the capacity of listening to the people who suffer, and that person is named Avalokiteshvara. “Avalokiteshvara” means “the one who is capable of listening.” We call that person the bodhisattva of deep listening, the bodhisattva of compassionate listening. That capacity to listen deeply with compassion has to be cultivated.

If you are a friend, you should be able to listen to your friend with compassion, and deeply, in order to really be a true friend. If you are a parent, you should be able to listen with compassion and deeply to your child. You should transform yourself into the bodhisattva of deep listening. Without deep listening, without compassionate listening, there will be no communication. In many cases, we truly love and wish that the other person will be happy. But we are not able to listen. Without the capacity of listening deeply, we cannot understand, and without understanding, love is not real; love is not possible.

UNDERSTANDING IS THE GROUND OF LOVE

In the teaching of the Buddha, love is something that is born from the ground of understanding. You cannot love unless you understand. A husband who doesn’t understand his wife, how could he love her? A wife who doesn’t understand her husband—if she does not understand the difficulties, the despair, the hope of her husband, how could she love him? That is why her practice as a wife is to listen deeply with compassion, with no prejudices, in order to understand her husband. If the father does not understand his son, his daughter, does not know what is the kind of difficulty his son is undergoing, how could that father love his son?

That is why it’s so clear, so simple to see that understanding is the ground of love. You cannot say that you love him or her unless you understand him or her. And understanding is not something that just happens like that. You have to practice looking deeply, you have to practice listening deeply in order to really understand. You have to be able to give up your ideas, your prejudices, because you may have an idea as to how that person can be happy, and you want to impose that idea on him or her. By doing so, you make him or her suffer, but you still believe that you continue to love him or her. You may be very sincere; you may have a lot of love within yourself, but that is not love yet. That is the intention to love. That willingness to love and to make a person happy, that is not love yet.

In order to truly love, you have to understand. That is why if we love someone we should try to understand him or her deeply, understand the kind of difficulties that person has, the kind of suffering that person has within himself or herself, the kind of deep hope, deep desire that the person has within himself or herself, the kind of obstacles that person is encountering in his or her daily life. You have to see all of that.

If you don’t see everything—and how could you see everything?—you can see a lot but not everything—you should ask him or her. You should go and say, “Darling, do you think I understand you enough?” She will tell you, he will tell you, if you ask with all your heart, “Darling, do you think I understand you enough?”

You can put the question to your partner, to your father, to your mother, to your daughter, to your son. And if it’s a real question, if that question is asked with all your being, that person will tell you and help you to understand more. When you understand, you will not continue to do or to say things that will make him or her suffer. You will help him or her to overcome the difficulties, and that is true love. True love comes from understanding.

The compassionate line cannot be set up by the telephone company alone. You have to pay something and they will set up a line. But that does not mean that with a telephone, you can communicate. Now the telephone is everywhere. You can pick up one everywhere in your city, and yet even with the telephone in your hand, you cannot communicate. In order to communicate, really, you have to be free of your views, your opinions, your judgments. You have to be free of your prejudices. And then with the absence of prejudices and judgments, you have the opportunity to look deeply and to see reality in itself, the reality of the other person. You declare that you love him, you love her, but you have not really understood him or her at all. You have to practice looking deeply, and you can ask that person to help you to understand. That is the practice of love.

You might think that it is the other person that you have not

understood. The fact remains that you have not understood yourself. You don’t know enough about yourself. You don’t understand the nature of your own suffering. You don’t understand the nature of your difficulties, the roots of your difficulties, and your desire. You are in a difficult situation. Because you don’t understand your own situation, you don’t understand yourself. You continue to be caught in the situation. You don’t even want to get out of that situation.

There is a young nun of nineteen years old who wrote to Thay the other day, and she told Thay about her life as a teenager. There was something very true in what she said. She said, “Thay, when you are caught in a situation, you might think that situation is normal, and you don’t see yourself in that situation. And that is why you don’t have a desire to get out of the situation unless someone comes and takes you to a faraway place, maybe a little bit higher, and you look back to your situation. Then you have a chance to see that that is a situation you don’t want to be in.” That is a kind of enlightenment.

If you don’t have the desire to get out of that situation, you will never get out of it. That is why the first thing you do is to have a desire to get out of that situation. You get the desire only by leaving that place, going to a faraway place, and looking back. Now you see that it is not a good situation. You and your beloved one are caught in that situation, and you want to get out, and you want your beloved one to get out also because both of you are suffering deeply every day.

So first of all, there should be a desire to get out. If you are the first one who is able to get out, you’ll be able to help rescue the other person and help the other person to taste freedom and true love. True love, true happiness, cannot be without freedom.

RELEASING OUR IDEA OF HAPPINESS

Every one of us has an idea of what happiness is, and we are committed to that idea. We say, “If I cannot get this and that and that, happiness will not be possible.” You describe your happiness. You have an idea of your happiness and you are striving in order to arrive at that.

Suppose a young person falls in love with someone else. In her passion, her attachment, she cannot see more than that person. She says that person is the only reason she has to be alive, her raison d’être. If she cannot marry that person, it’s better that she dies; her happiness cannot be possible without that person beside her. Her idea is to get him or to die. For those of us who have not gotten into that situation, we are able to see that happiness can come from every direction. Happiness can come from the west, from the east, from the north and the south, from above, and from below. And if we are committed to just one idea of happiness, we block all the other avenues. Happiness comes and knocks on your door. “Please open; I am happiness!” You say, “No, you are not happiness.” You refuse every opportunity to be happy because you are already committed to one idea of happiness. Many young people commit suicide because they cannot marry the person they love. In the history of love there are plenty of things like that.

Those of us who are free, we see that happiness can come from everywhere and at every moment. The morning sunshine can bring happiness. Half an hour of walking leisurely can bring happiness. Having a cup of tea with our friend or our teacher can bring happiness. Happiness can be there every moment of our life. Why do we have to commit ourselves to just one idea of happiness?

This morning we spoke of joy and happiness born from the practice of releasing, of letting go. The first thing we have to let go is our idea of happiness. If we are able to let go of our idea of happiness, happiness will come very easily. If you are not happy, it may be because you are holding very hard to your idea of happiness. If your beloved one is not happy because you keep imposing your idea of happiness on him or her, it’s very clear, very simple.

FOUR ELEMENTS OF TRUE LOVE

In the Buddhist teaching of love, we learn that there are four elements that can provide true love and happiness.

The first element is maitri. “Maitri” means friendship, brotherhood. The word “maitri” comes from the root mitra, friend. When you love someone, you offer your friendship, your brotherhood. Friendship and brotherhood do not deprive him or her of his or her freedom. When you love, you maintain your whole freedom, and you help maintain the freedom of the person you love. You don’t deprive him or her of his or her freedom with your offering of happiness.

In your relationship, the other person asks the question whether you have maitri to offer him or her. We are on an equal basis. By loving you, I retain my freedom. And by loving you, I respect your freedom. That is maitri, which we translate poorly as “loving kindness.” There should be a better word.

A friend who does not understand a friend cannot really offer his brotherhood, his friendship. That is why, to cultivate maitri, you have to cultivate understanding. You spend your time with him or her with mindfulness, and you discover every day his need, his difficulties, his obstacles, his deep aspiration, and on that base of understanding you offer maitri, happiness.

The second is karuna. “Karuna” means the capacity to understand the suffering and help remove it, transform it. The person you love has suffering in him or in her, has difficulties in him or in her. As someone who loves him or her, you should be able to identify that suffering, that difficulty, and try to help remove it. And the capacity of helping remove that suffering is called compassion. Transforming suffering in the person you love, because you see the suffering in your beloved one. And if you are not able to help him or her remove that suffering, you are not a real lover.

We used to translate “karuna” as “compassion.” The other person suffers, and you suffer with her; you share the suffering. That is the word “compassion.” But in true love, you don’t have to suffer with him; you understand only, and your capacity of understanding helps the other person not to suffer anymore.

When a patient comes to a doctor, the doctor is supposed to be able to see what is wrong within the patient, what is the sickness and the root of the sickness. That is exactly karuna. The doctor, after having identified the illness and the root of illness, is capable of prescribing something for the removal of that illness. The doctor doesn’t have to suffer together with the patient. That is why the word “compassion” is not perfect in translating “karuna.”

The Buddha sits there, and people come and cry with him, and he doesn’t have to cry with them. He says, “Dear friends, I understand your suffering, but there is a way for you to go.” If the Buddha spent his time crying with people, he wouldn’t have any time left in order to help with the transformation and healing!

So, in your relationship, ask whether you have the element of compassion in your love. If you do, then you are being very helpful. You are helping that person to suffer less. Your presence already helps that person to feel better. Your speech, your actions, your capacity of listening deeply, help him or her transform and remove the suffering. That is the element called karuna. In our relationships, we should be able to cultivate karuna every day.

The third element is called mudita, joy. The kind of joy that is shared by both. If in your relationship there is only sadness—you make him cry and he makes you cry—that’s not love! True love should include joy. You are able to enjoy his joy, and he is able to enjoy your joy, because you are no longer two separate entities. You are one with the person you love. That is why, when you see that person happy, you feel very happy. And when you see that person unhappy, you are able to do something in order to help. You consider his happiness as yours. You don’t say, “That’s your problem.” In true love, there is no statement like that. Sympathetic joy. Your joy is his joy, and his joy is your joy.

You have to be able to offer joy. The question is, in your relationship, are you able to offer joy? Or do you make her cry all the time? If you make him or her cry all the time, that’s not true love. The willingness to love, the willingness to make him or her happy—yes, it may be there, but the capacity to love, to make him or her happy, is not yet there. It has to be cultivated.

The fourth element is upeksha. “Upeksha” means “nondiscrimination.” This is a higher form of love. You love him not because he belongs to the same race, has the same kind of skin color, or shares the same kind of spiritual path. It’s not because of that. You love that person because that person suffers and needs your love. That is the path of nondiscrimination. Suppose you have four children, and you realize that all of them are your children. You don’t want to prefer one over the three others. You practice upeksha, equanimity.

You love Mr. Kerry because Mr. Kerry speaks for you. But you don’t love Mr. Bush, because Mr. Bush is doing things you don’t like. There is no equanimity in your love. Even if John Kerry has ideas that are close to you, then you still have to love Mr. Bush. You have to say, “Mr. Bush, I have to help him, because if I am able to help him, I help the other half of the population. I have to do something in order to offer him more understanding, more compassion, so he will handle the problems in the Middle East and Iraq in a more compassionate way.” You have to love him. So you love both of them. For American voters, it is very difficult to persuade them to love both. I have tried, but I have not succeeded.

Equanimity is inclusiveness. When you love, your love should include everyone, whether he is black or white or brown or yellow, whether he is Catholic or Protestant or Jewish or Buddhist or communist. You have to love them all. That is why equanimity reveals a higher level of love. It’s not because the young man is your son that you have to love him and you exclude the other young men. You are a true lover. You have to include sons of other families. When you can love the sons and the daughters of other families, you are in a position to be a politician, to be a teacher. And therefore all of us have to cultivate the quality of equanimity. The king is supposed to love everyone in the country as his own sons and daughters. The king is supposed to practice equanimity.

In the tradition of Buddhism, it is said that maitri, karuna, mudita, and upeksha can be cultivated every day because these are four qualities that have no limits. Infinite love. And the four elements are called the Four Unlimited Minds, because the maitri can become unlimited. This kind of love we may call love without frontiers. When you have developed your love to that level, you are called a bodhisattva; you are called a buddha. There are buddhas and bodhisattvas in our midst, in the world.

There is an organization of doctors who want to serve people everywhere, not only in France, in Great Britain, but also in Africa, in Asia. They call themselves Médecins Sans Frontières. Sans frontières, that is the phrase: love without limits, frontiers. You can develop these four qualities because when your heart is able to embrace everyone, every living being, it no longer has any frontier. Your heart becomes immense. When the love in your heart is like that, you don’t suffer anymore. You can accept everything.

The Buddha gave a very beautiful image. He said, suppose you have a bowl of water and you have a handful of salt, and you pour all the salt into the water and you stir. The water becomes undrinkable; it’s too salty. You cannot quell your thirst because that is a salty solution.

But suppose you throw that handful of salt into a river. Although the salt is diluted in the water, people continue to drink the water and they don’t suffer at all. Why? Because the river is immense. That is why a handful of salt cannot make the river suffer. Even if you throw handful after handful, one hundred handfuls, the river is still immense. The river still doesn’t suffer. So the technique is to enlarge your heart, to make it into something unlimited. When your heart becomes immense, you can accept everything. The small things, like a handful of salt, do not make you suffer anymore. If your heart is small, small things can make you very unhappy. But if you have a heart that can include everyone, every living being, you don’t suffer anymore. That is the quality of equanimity, all embracing.

SETTING UP A COMPASSIONATE LINE

Once we have karuna, maitri, mudita, and upeksha, we have a tremendous amount of energy within us, and the line of communication can be established very easily. We can listen very deeply with compassion. We can understand the other person right away. What we say, what we do, will not make him or her suffer anymore. And everywhere we can establish that compassionate line within us and the other person.

The bodhisattva of love, Avalokiteshvara, is in you. You are able to listen, to understand, and you are free. That is why in our relationship we should be able to establish a communication line, and the current that circulates in that line should be the current of maitri, karuna, mudita, and upeksha. And when the other person listens to the voice of compassion, of loving kindness, of nondiscrimination in us, the suffering in him or her will vanish, and the idea to kill himself or herself will vanish. That line will be able to save many people.

So if, in your relationship with someone—whether that is your partner, your mother, your husband, or your wife—there are difficulties, there is suffering, you should be able to set up that line of communication. Work within yourself first before you set up the line. And after the line is ready you can call him, call her. “Darling, I know that there is a lot of suffering, uneasiness, difficulty in you. I know in the past I have said things, I have done things that made the situation worse. Now, I understand. I don’t want to continue like that. So darling, please tell me about your suffering, your difficulties, your deepest aspiration. I am free now. I am able to listen to you.”

And the line begins to work.

“I know that I have not understood you enough. Now my deepest desire is to understand you deeply, so that I will not make you suffer anymore like I have done in the past.” That is what we call loving speech, compassionate speech, thanks to the line we just established, the compassionate line.

You may like to give a color to that line. It should not be red. And thanks to that line of communication you will be able to help transform the other person and bring him or her happiness and freedom. When you speak through that line with compassion like that, the other person will tell you and help you to understand him or her more.

I wish you good luck, a good practice.

NOURISHING GRATITUDE

Everyone is invited to stay for walking meditation, enjoying every step you make, walking with freedom, like walking in the Kingdom of God. After that, we will have lunch together. Today, Thanksgiving Day, we have a different kind of lunch, celebrating our togetherness, nourishing our thankfulness, our gratitude. This morning I spoke about four kinds of gratitude: gratitude we show to our parents, who have given us life; gratitude toward our teacher, who tells us how to love, to understand, and to live happily in the here and the now; gratitude to our friends, who support and protect us in difficult situations; and gratitude to living beings in the animal, vegetable, and mineral realms. We are grateful for the trees, the clouds, the mountains, the rivers, the birds, the squirrels, even the bacteria.

And I have a fifth kind of gratitude—to my students, because my students give me a lot of happiness. This is a day when I want to offer my gratitude to my students, my disciples. They are practicing wholeheartedly. They are bringing transformation and healing to themselves, to their families, and to the Sangha.

Transcribed by Greg Sever. Edited by Natascha Bruckner.