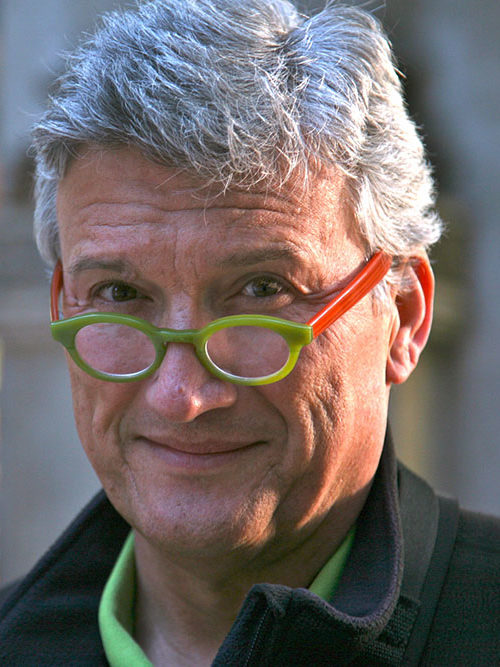

Interview with Dr. James Doty

By Sarah Caplan

Last April, my meditation group attended an event at Stanford University entitled “Conversations on Compassion with Sharon Salzberg.” Sponsored by Stanford’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE) and hosted by the center’s founder and director,

Interview with Dr. James Doty

By Sarah Caplan

Last April, my meditation group attended an event at Stanford University entitled “Conversations on Compassion with Sharon Salzberg.” Sponsored by Stanford’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE) and hosted by the center’s founder and director, Dr. James Doty, it was one of a number of free public talks that have included the Dalai Lama, Amma, and Thich Nhat Hanh. What stayed with me afterwards was a feeling of gratitude; how fortunate for those of us who live near Stanford to have access to these talks—and for free! I wondered how Dr. Doty, a neurosurgeon, had seemingly unfettered access to some of the spiritual luminaries of our time. A few weeks later, I was surprised to learn that Dr. Doty and I were parents of children who go to the same school. I shared with him my interest in Thay’s teachings and he told me that he had recently attended the Pope’s summit to end slavery with Sister Chan Khong and other spiritual leaders. I became even more intrigued. How did a brain surgeon become interested in compassion? How do you go from seeing the brain as a bodily organ to delving into the esoteric world of what goes on inside it? — Sarah Caplan

Sarah Caplan: Before we get into your work with CCARE, tell me what your early life was like. How did the seeds of your interest in compassion begin?

Dr. James Doty: I grew up in Lancaster, California. It’s in the high desert and can get very hot. I tell people at times it seemed like hell. My father was an alcoholic and my mother was an invalid. She’d had a stroke and was paralyzed, and also had a seizure disorder and was chronically depressed. In fact, she tried to commit suicide multiple times. Neither of my parents had gone to college. We were on public assistance.

Even as a young child, I was self-aware enough to question why some people who are so blessed and have so much don’t become more generous; often they become more greedy and unhappy. And then the happiness and joy I would see with people with the most minimal of things, but who had shelter, food, clothing, and their children were safe—they were just the happiest people on earth. That stayed with me.

A seminal event happened to me when I was twelve. I was at a transition point where I felt I had no future and I was becoming a delinquent. One day I walked into a magic shop and the owner was not there, but his mother was there. She knew nothing about the magic store. She was a little overweight, she was wearing a muumuu, she had long gray hair and just the happiest countenance. A big smile on her face immediately greeted me. She and I began chatting, and she was very interested in me. At the end of it, she said, “I’m here this summer for another six weeks. If you come in every day, I’ll teach you something.” I showed up every day for six weeks, for a couple of hours a day, and she taught me a mindfulness practice.

SC: Do you know what tradition?

JD: I don’t know, but it was related to having a mantra and looking at a candle. She taught me the power of positive thinking and a visualization technique. Prior to that, I felt like a leaf being blown by an ill wind. After that—and I tell people it’s my first experience with neuroplasticity—I went from a mindset where my possibilities were limited or non-existent to a mindset of unlimited possibilities. It shows you that it’s not so much the events that happen to you in life; it’s how you respond to the events. That was an amazing lesson. At the end of this, I didn’t have despair or anger over my situation. I just accepted that that was reality. It didn’t need a response; that was just the reality.

So, my first encounter with meditation had a profound impact on my life. Some years later, I was at a used bookstore browsing, and on the shelf beckoning me was a somewhat worn copy of Thich Nhat Hanh’s book, The Miracle of Mindfulness. I took it home and ultimately it became a book that I would go back to frequently to give me clarity and insight. It is now much more worn than when I first got it, and it has become a friend.

But at twelve years old, as soon as my mindset changed, it opened up all sorts of possibilities. I joined the Law Enforcement Explorers with the sheriff’s department. We’d go around on patrol and do voluntary stuff in the community. One day I was working as a jailor, and my father was arrested.

SC: That’s pretty painful.

JD: Well, it’s humiliating and degrading—or at least you think it is. These are emotions that you’re creating yourself, right? The interesting thing is with my father’s arrest, it actually gave me an incredible insight. I recognized that my parents’ actions were not me. Unfortunately, many people—kids especially—think that if their parent does something, it is a reflection on them. I realized it didn’t, and I didn’t have to hold my head in shame. So in some ways that was a liberating experience, although it’s not one I would want to relive or have anyone go through.

SC: Did you continue the practice that the woman taught you?

JD: I did use it. I’ll give you an example. I knew I wanted to be a doctor. I’d been impressed by a doctor who came to my class when I was in fourth grade, and I really felt I wanted to be of service. But although I made it into college, it was a very chaotic situation. I didn’t have enough money. Something would invariably happen to one of my parents, which would require me leaving, and I had no understanding of how college worked. For the first quarter, I essentially flunked out. They actually told me not to come back, but I convinced them to let me come back.

Then it came time to apply for medical school and you had to apply to this pre-med committee. I went to turn in my application and request an appointment, and they refused to give me one. The woman said, “Giving you an appointment is a waste of our time because you’re never going to be accepted.” Talk about demeaning, devastating, and humiliating! So I said, “Well, you may believe that, but I’m not leaving here until you give me an appointment.”

So they did. I went into this room with three professors, two of whom were women, and they were sitting like this [leaning back with arms folded], and I think one of them said, “We understand you demanded this. Why do you think we should waste our time chatting with you?” I lectured them for about an hour and didn’t let them speak. I said, “What right do you have to destroy people’s dreams? Show me one shred of evidence that having an above average intelligence has any impact on how well you do in medical school.” There’s not one bit of evidence. I said, “All this is an arbitrary way to dismiss people, and you know nothing about me.” At the end of this somewhat one-sided discussion, they were all crying. I’d taken them from looking at me as a number to looking at me as a human being. Once you do that, people cannot dismiss you. They ended up giving me the highest recommendation. I applied to one medical school—Tulane in New Orleans—and was accepted.

To share how that can come full circle: I ended up making a lot of money in the dot-com boom and from a medical device company that I had run, and I gave every penny I made to charity, which was tens of millions of dollars. I gave to Tulane. They were responsible for my success and they took me in when I only had a 2.53 grade point average. I didn’t have enough credits to get a bachelor’s degree, but they accepted me. I’m actually the largest donor to the medical school and I endowed the dean’s chair. At Stanford, I set up an endowed chair and gave multiple millions to research. I support health clinics all over the world, AIDS/HIV programs.

SC: At what point did CCARE come about? What’s interesting to me is the intersection of spirituality and science, compassion and neuroscience—two areas that are usually mutually exclusive.

JD: It’s funny because I’m an atheist and I have no belief in anything except for this moment. As Thay says, oftentimes one is lost in regret related to the past or experiencing anxiety about a future that does not yet exist. While many have faith in something beyond the present as a means of decreasing anxiety about the unknown, I only know the present and try to live in that place, knowing that it is all I am certain of. I’ve never felt that kindness or compassion required dogma.

At Stanford, I created a group of researchers to work with me to look at the topic of compassion. It ended up being something we called Project Compassion, which I funded initially. One day I was walking through the Stanford campus and it popped into my head—I can’t tell you why because I had no interest in the Dalai Lama—that it would be really interesting to invite the Dalai Lama to come to Stanford. So I finagled a meeting with him. I explained my interests and the work we had begun, and he was very intrigued and asked some interesting questions. At the end, he began an animated conversation with Thupten Jinpa, his translator, in Tibetan. Jinpa said to me, “Jim, His Holiness is so impressed with this program that he would like to make a personal donation.” That ended up being the largest donation he’d ever given to a non-Tibetan cause at the time. And right after that, two individuals each gave $1 million. That’s how the Center was created. The extraordinary thing was that Jinpa, who has a PhD from Cambridge, began working with the Center and was instrumental in creating the Compassion Cultivation Training program, an eight-week educational program that combines contemplative practices, psychology, and scientific research to help people live a more compassionate life.

SC: After watching many of your interviews online, I’m curious to know how you saw Thay’s teachings on compassion. Thay said, “Maybe scientists have the way to measure this kind of intensity that can be generated when you have all these people meditating together.” He was calling on scientists like yourself to help with this cause.

JD: I think that evolved individuals, like Thay and others, understand that in a secular world, having data gives people evidence of the practicality of doing something. What science has done over the last several decades is validate the power of meditative or contemplative practice to positively affect people’s lives and those around them. It has this rippling effect.

You would think that you wouldn’t have to argue about the value of kindness or compassion, but unfortunately in a secular or evidence-based society, sometimes you do if you want to implement programs in the public or non-religious domain. Now, it can be argued that Buddhism is more of a philosophy than a religion, but some people look at it as a religion.

If you can then deconstruct Buddhism by taking those parts of it that we know have a positive physiologic effect, and by keeping those parts of the dogma that don’t diminish it into simply an exercise in attention, so it is still imbued with the importance of compassion, then I think it becomes very, very powerful. That’s what we’re seeing. Science has borne out that when you live with compassion intention, it actually improves your health and increases your longevity.

It shouldn’t be surprising because, as a species, we evolved with compassion as a central component. To have abstract thinking, to have complex language, required an increase in the size of your cortex, but it also required that the mother primarily be attentive to a child who could not survive in a harsh environment, even after ten or fifteen years. So there has to be this incredibly strong genetic component that allows for the mother to recognize that her offspring are suffering or in need of her. Then as we evolved to hunter-gatherer tribes, compassion was just as important because until 6,000–8,000 years ago, we lived in groups of ten to fifty, and if someone in that group was suffering and it was not recognized, it potentially put the entire group at risk.

This is part of the problem of modern-day society. Many of us don’t have someone who is attuned to our suffering, nor do we necessarily allow people to get close to us, to care for us, because we’re afraid of what they might think of us. We don’t allow ourselves to be vulnerable. In the old days you would live with your parents, your grandparents, all your relatives and friends within a small, local area, and if an individual was suffering, the community would reach out and embrace them and help them. Now, people are distributed all over the world, and they’re working in environments that are stressful and demanding, and they don’t have that person. Twenty-five percent of Americans when surveyed said that when they were suffering they had no one to talk to—no one. Can you imagine? We should all open ourselves up to be a vessel to care and to alleviate suffering. Sometimes it’s simply a hello or a hug or showing somebody that you are really, as Thay would say, practicing compassionate listening. When we’re actually there, it’s very, very powerful.

SC: How has your understanding and practice of compassion been impacted by Thay’s teachings?

JD: I am reminded of the impact his book, True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart, had on me when I read the line, “You must love in such a way that the person you love feels free.” It led to a deep reflection on the challenge of loving others whom one sees as different or whose views are in conflict with one’s own. Further, it allowed me to recognize my own suffering and to be more gentle with myself and understand that often it was my own suffering that resulted in negative reactions to others.

SC: In the interview with Amma, you talked about suicide. Here in Palo Alto, we’re having a rash of teenage suicides and we’re one of the wealthiest enclaves in the world. How is it that kids who seemingly have everything feel so bereft?

JD: People ask me, “How is it to be in the presence of the Dalai Lama or Thich Nhat Hanh or Amma?” When you’re in their presence, you are embraced by unconditional love. When I interviewed Thay, being in his presence was really a profound experience, as one immediately feels the depth of his embracing warmth and love. I was struck not only by the depth of his kindness but also his patience. And I was again reminded of the power of presence.

This is what so many of us are missing, to feel that the people we are connected to totally accept us and accept that we’re all frail, fragile human beings. This is the problem with children who commit suicide. In their minds, sadly, their value is not in who they really are; their value is related to their performance in school. If they can’t live up to what is expected of them, then in their mind, they’re worthless. They feel that their parents do not care for them at all or love them. How horrible to be dismissed and discarded, not because of who you are deep inside but simply because you didn’t do well.

SC: It’s ironic—in poor countries, kids don’t have access to education or health care or the things we take for granted in the US, and they would give anything to have this kind of life; and here are privileged kids killing themselves because it’s not serving them.

JD: This is the problem with the West. It saddens me because people have a false belief that by coming to America they will have everything. Instead of a life perhaps without luxuries but with deep connection with family or traditions, they chase something that offers no sustenance, which is consumerism, the acquisition of goods—thinking that acquiring more makes you happy. And it certainly does not, at all.

SC: What’s nice about your work is that when you did acquire wealth, you achieved such happiness in giving.

JD: I tell people that giving everything away has actually resulted in the best times of my life and has allowed me to interact with some of the most amazing people in the world.

To learn more about CCARE, visit http://ccare.stanford.edu. James Doty’s interview with Thich Nhat Hanh, hosted by CCARE at Stanford University on October 24, 2013, can be seen at http://ccare.stanford.edu/videos/conversations-on-compassion-thich-nhat-hanh-2/

Transcribed by Sarah Caplan. Edited by Janelle Combelic.

Dr. James Doty’s book, Into the Magic Shop: A Neurosurgeon’s Quest to Discover the Mysteries of the Brain and the Secrets of the Heart, was published in February 2016. The book was endorsed by Thich Nhat Hanh, who wrote: “In this profound and beautiful book, Dr. Doty teaches us with his life, and the lessons he imparts are some of the most important of all: that happiness cannot be without suffering, that compassion is born from understanding our own suffering and the suffering of those around us, and that only when we have compassion in our hearts can we be truly happy.”

Sarah Caplan (shown with her son, Mischa) is a graphic designer living in East Palo Alto, California. She first learned about Thay in the early 1990s when her dying mother shared with her The Miracle of Mindfulness, which brought solace and clarity to them both. In 1993, Sarah participated in a walking meditation with Thay in New York City and has subsequently been blessed to attend several retreats at Deer Park Monastery with her husband and two sons.