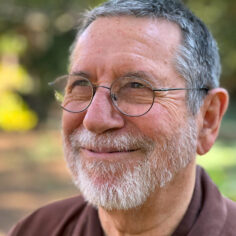

By Leslie Rawls, Mitchell Ratner, Natascha Bruckner in June 2019

Dear Thay, dear community,

When I first met Thay (Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh) in 1990, I was immediately captivated by the presence, ease, and joy that seemed to radiate from him, whether he was giving a Dharma talk or walking in a park.

By Leslie Rawls, Mitchell Ratner, Natascha Bruckner in June 2019

Dear Thay, dear community,

When I first met Thay (Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh) in 1990, I was immediately captivated by the presence, ease, and joy that seemed to radiate from him, whether he was giving a Dharma talk or walking in a park. I was then a relatively new practitioner of meditation and mindfulness. Although by conventional standards I was doing well, inwardly I had felt cut off from life, and I had often suffered from dissatisfaction, self-doubt, and anxiety. I felt that I could learn a lot from Thay. Looking back now at that moment in time, I believe I greatly underestimated the transformations that Thay and the Plum Village practices would bring into my life.

Like the Buddha and the early Mahayana teachers, Thay had a clear diagnosis and treatment for the prevailing spiritual illnesses of his time. He often calls what he teaches engaged practice, or engaged Buddhism. In a 2008 talk in Hanoi, he explained:

When we speak about engaged Buddhism, we speak first of a kind of Buddhism that is present in our daily life at every moment. When [people] hear about engaged Buddhism, they think of fighting for social justice, fighting for human rights, organizing demonstrations, and so on. But that is not true. That is part of the practice, but not the basic part. The basic part is to have the practice alive in every moment of your daily life. You should be there in order to attend to what is happening in the here and now, in the realm of the body, the realm of the mind, the realm of environment.

Thay began writing about engaged Buddhism in 1954, following the postcolonial division of Vietnam. Traditional relationships and ways of life had been shattered, and many people were pressured by communist and anti-communist ideologues. Thay’s teachings on engaged practice offered many people a much-appreciated spiritual grounding and direction.

A decade later, in 1964, amidst the horrific suffering caused by the destruction and ideological fervor of the Vietnam War, Thay created the Order of Interbeing (Tiep Hien) and formulated the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings. Engaged Buddhism took a new form. In the Charter of the Order of Interbeing, Thay wrote, “The aim of the Order is to actualize Buddhism by studying, experimenting with, and applying Buddhism in modern life with a special emphasis on the bodhisattva ideal.”

Thay ordained the first Order members, three women and three men, in February 1966. The growth of the Order, however, was interrupted by Thay’s advocacy in the United States for an end to the war and his subsequent exile from Vietnam. The next ordination occurred fifteen years later, in 1981, in the United States. In the following years, the number of ordinations grew steadily, coinciding with the development of Plum Village monastic centers, an expanding readership for Thay’s books, and a worldwide proliferation of lay practice groups and centers supporting the practice of engaged Buddhism. When I was ordained in 1993, there were about 100 members of the Order of Interbeing. Today, worldwide, there are about 1,000 monastic members and 3,000 lay members.

The Order of Interbeing and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings have continued through the years to be very dear to Thay. The initial seed of this issue of the Mindfulness Bell came from a request made by Thay in 2012 to solicit and publish accounts of his students’ practice of the Fourteen Trainings. Our call for submissions brought a robust response. This issue of the Mindfulness Bell looks deeply into the practice of the Fourth Training (Awareness of Suffering), the Seventh Training (Dwelling Happily in the Present Moment), and the Fourteenth Training (True Love). Future issues will explore the other trainings.

Also included in this issue is a wonderfully rich Dharma talk, True Transmission, which Thay offered on August 22, 2001, at Deer Park Monastery. For me, an underlying energy permeates the talk: Thay’s gentle encouragement to practice wholeheartedly so that we will embody the living Dharma. Along the way, Thay explains that to be an Order Member or a Dharma teacher is not about official ceremonies or brown jackets; rather it is about Sangha building, mentoring, and finding freedom and happiness in each present moment.

Reading through the articles that Dharma teachers, Order members, and aspirants sent to us, I was impressed with the depth and sincerity of the writing. For them, mindfulness is not a part-time practice; it is at the center of their lives. My hope is that you, too, will be touched by Thay’s talk and each article, and that the engaged practice of the Plum Village tradition will enter more deeply into your everyday life.

Many blessings,

Mitchell Ratner

True Mirror of Wisdom

Dear Thay, dear Sangha,

The Mindfulness Bell’s managing editor, our dear sister Hong-An, is recovering from an illness, so we are writing this editorial letter in her place. Her recovery is going well and she intends to return to work on the next issue.

Hong-An collaborated with guest editor Mitchell Ratner to choose this issue’s theme and gather articles about nourishing ways to practice the Fourth, Seventh, and Fourteenth Mindfulness Trainings. She also worked with the graphic designer, Helena Powell, to create a beautiful new cover design. Since Hong-An stepped away, our Sangha has come together beautifully to take care of our community’s beloved magazine. Many skillful hands, hearts, and minds have joined in to lovingly edit, proofread, gather photos, and tend to the many details that bring this magazine into your hands.

We have heard Dharma teachers share the analogy that Sangha is like a rowboat. Some people are rowing the boat. Others are riding in the boat. Sometimes, we have the strength and capacity to row. Other times, we need to simply ride—to rely on others to row for us. We take turns as we need to. Yet all the time, the rowboat of our practice carries us together. As this issue of The Mindfulness Bell came together, we felt the stability and resilience of our practice and the robust, generous support of our Sangha.

As the rowboat of our practice moves gently down the stream, some of our beloved teachers and friends may not be able to row for a while, or they may transition to other places and manifestations. Our practice breathes us through these transitions. We take up their oars, take up their loving work. The Buddha and Thay within us also take the oars, as we do. We go forward together.

With love and gratitude,

Natascha Bruckner, True Ocean of Jewels, Care-Taking Council Member / former Managing Editor

Leslie Rawls, True Realm of Awakening, Volunteer copy editor / former Managing Editor

Heather Weightman, Awakened Stream of the Heart, Subscriptions and Marketing Coordinator