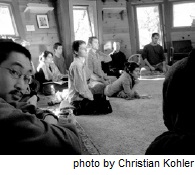

A Dharma Festival for Young Adults

In the fall of 2005, a group of young adult practitioners gathered for a weekend retreat in rural Northern California. Here are reports from a few of the participants.

Alissa

During the winter retreat of 2004 young practitioners in the US came together for the first time in significant numbers. We had a chance to confide in each other: “I’m by far the youngest one in my Sangha,” and “My friends and family don’t get what I’m doing,” were commonly shared sentiments.

A Dharma Festival for Young Adults

In the fall of 2005, a group of young adult practitioners gathered for a weekend retreat in rural Northern California. Here are reports from a few of the participants.

Alissa

During the winter retreat of 2004 young practitioners in the US came together for the first time in significant numbers. We had a chance to confide in each other: “I’m by far the youngest one in my Sangha,” and “My friends and family don’t get what I’m doing,” were commonly shared sentiments.

In the Bay Area, we are fortunate to have many young practitioners living nearby. We get together often, to practice and talk about the particular challenges our generation is facing. The most frequent concerns are around relationships and sexuality, followed closely by how to earn a living doing work that is meaningful.

We decided to take the questions head on:

• How do I find the man/woman of my life and craft a mindful relationship?

• How do I date and have sexual relationships in a mindful way?

• How do I build mindful relationships with my parents, family, and friends?

• How do I build a career that fulfills me and embodies my practice (right livelihood)?

• How do I choose where and how to live in a way that meets my needs as an individual and the needs of my community?

Perhaps what made the retreat so powerful was that it was done entirely by young adults: the organizing, the recruiting; we even had one of our Dharma brothers do the cooking. When monastics from Deer Park accepted our invitation to come support us, it became a meeting of the fourfold Sangha: monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen, all of us in our twenties and thirties.

Many times during the organizing process, we were asked: do you really want to limit it to young people? And after repeated examination, the answer was always: this time, yes. Drawing a circle of young practitioners, we give ourselves a chance to stop wondering when the teacher will arrive to invite the bell and present the Dharma talk. We see more clearly the elders that are among us already. We see that the teacher and I are one, that we already have the answers, and that now is the time to wake up to the teacher within ourselves.

Alissa Fleet, Boundless Transformation of the Heart

Anna

When we came up with the name for our retreat, Joyful Togetherness, little did we know how applicable it would be. The answers, for many of us, were in the experience of the retreat itself. We touched true togetherness and experienced the issues with a Sangha that truly understood.

There was no single moment of revelation for me. There were quite a few moments when I felt or acted with strife, or raced around on that edge that I love so much where I am the orchestra leader, and each instrument, with perfect precision, falls into place. But at the end of the retreat, what I had wanted so much from the monastics—an experiential realization of the Dharma, and an answer to the questions that came, not in words, but in experiential understanding—had become a reality.

Each question, as articulated originally, was an analytic way of approaching life, a way of cutting ourselves into pieces. In the retreat, as I was surrounded by loving faces, kind hands, gentle touches, the questions collapsed back into themselves, into daily moments, into small decisions and gestures, into me. The question of mindful sex was no longer urgent, not because it wouldn’t manifest, but because it was no longer by itself a question. It was rather a piece of a greater fabric, a wave in the ocean of many lives, manifesting when conditions were correct, not manifesting when conditions were not correct.

Each moment, each step, each gesture, each word, we rediscover who we are and we remake the world anew, so that we are truly free. In every action we carry with us all of our ancestors and all of our descendants, so that we are never alone. We are the consequence and resolution of our histories. Within us, all things end and all things begin. Just like this.

Anna Halpern-Lande, Sincere Refuge of the Heart

Gary

As our retreat committee was planning the retreat, there were times of doubt and confusion because of the scale and complexity of the retreat. Northern California hadn’t hosted monastics in some time and there was a feeling of pressure that we wanted to get it right. And yet we hadn’t received official confirmation that the monastics would come. At one point we committed to hosting the retreat whether the monastics were there or not; and whether anybody registered for the retreat or not, for that matter. It was an exhilarating moment in our Sangha when we came to this conclusion. We had no assurances, save for our resolve and our commitment to do the retreat, even if it was just for ourselves.

I wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted from the retreat. I had been asking these questions for such a long time with little fruit. One night as I was studying Dogen’s Instructions for the Cook it struck me, “I want to explore the practice of being the cook; or, as the word is given to us from Japan, Tenzo.” This was well received and the planning began immediately. Following are some insights I gained from my Tenzo practice:

If you are a good cook but a poor practitioner, your food will glisten like fool’s gold. If you are a sensible practitioner and a fair cook, your food will shine with the light of love and insight. Avoid cooks who play music or radio or get caught in diversions; who make innumerable trips downtown; who don’t participate in the community by attending morning and evening sits; who don’t partake in the family sharing or sleep in community; who avoid the intimacy and rhythms of practice. You may as well order pizza and Chinese takeout if your Tenzo is not a full-minded practitioner. The quality of your cooking is not measured in tastes and textures. But the harmony and purity of your heart is exuded in the food, in the kitchen community, and your overall practice.

Gary Brain, or as his Dharma brothers and sisters like to call him, Honey Bear of the Heart Mind

Tim

I remember sitting under oak trees by a quiet creek in a circle of forty young people as we each held one long yellow ribbon that connected us. In silence and in discussion, in listening to Dharma talks and in walking together under the starry sky, what made our retreat so special was sharing the gift of mindfulness practice with so many young people whose questions and fears were so close to my own. I knew as we listened to the sound of the bell that my questions, “How can I support myself without losing my joy?” “Will I be able to have a relationship and family that reflect my aspirations?” were shared by many others, and the togetherness was comforting.

I am twenty-six years old, and people of my generation have the task of finding spirit not by dropping out of society, which we have seen creates isolation, but creating a spiritual life as part of society. While many of us do drop out for a time, we are coming to see the eventuality of our return, which makes possible the transformation of society. As the forty of us smiled and sat and ate together, we were and are creating mindful lives for ourselves and for society. The support that we offer each other as we are faced with choices about family, livelihood, and sex was clear water for parched lips.

Tim Desmond, True Mountain of Joy