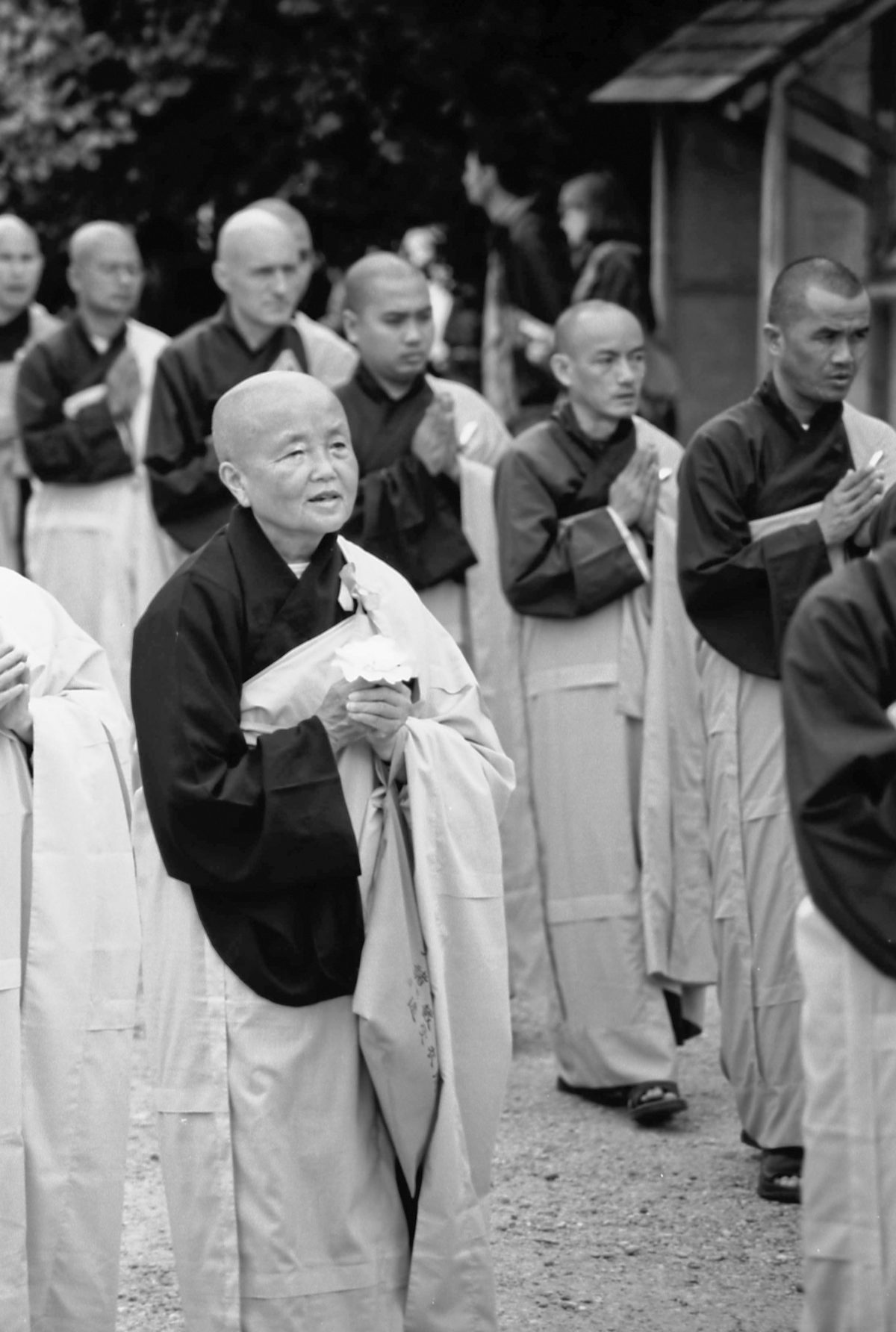

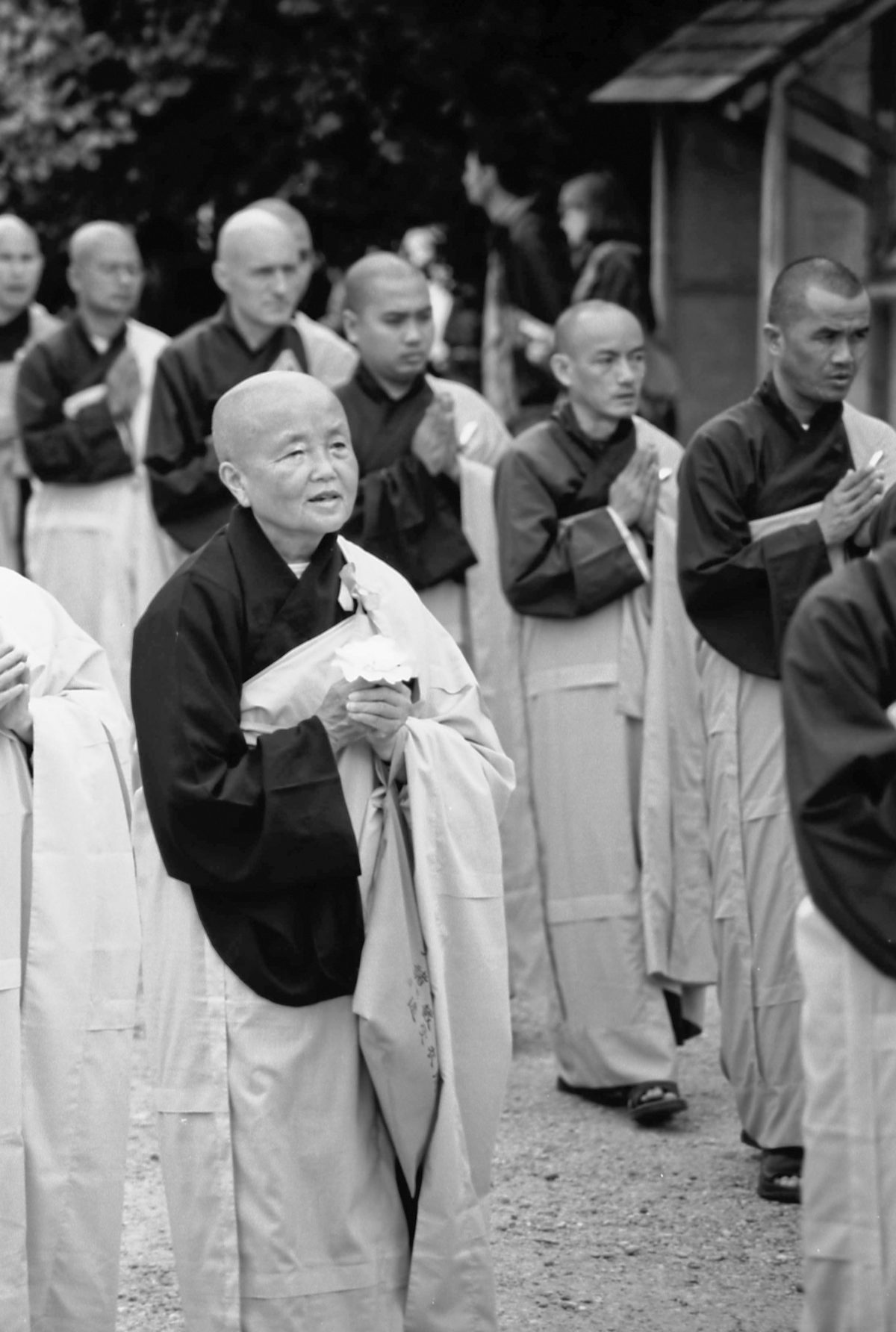

A Portrait of Sister Chan Khong

By Eveline Beumkes

Her original name is Phuong; her monastic name is Chan Khong (True Emptiness). Thich Nhat Hanh and Sister Chan Khong started Plum Village together in 1982. That Plum Village has become what it is today and that people all over the world have been inspired by Thay’s teachings is,

A Portrait of Sister Chan Khong

By Eveline Beumkes

Her original name is Phuong; her monastic name is Chan Khong (True Emptiness). Thich Nhat Hanh and Sister Chan Khong started Plum Village together in 1982. That Plum Village has become what it is today and that people all over the world have been inspired by Thay’s teachings is, to a great extent, a result of Sister Chan Khong’s enduring support and untiring initiative. Feeling grateful for having come in contact with Thay’s teachings is feeling grateful to Sister Chan Khong in the very same breath.

I first met Thay and Sister Phuong in 1984, during a meditation weekend in Amsterdam. In the evening, there was a special program with Vietnamese music. At one point, the music stopped abruptly, and Sister Phuong began to sing. I was deeply touched by her voice. Never had I heard someone sing like that. She sang my heart open, and I cried and cried, not understanding what was happening to me.

During the first summer I spent in Plum Village, Sister Phuong wasn’t yet a nun. She had lovely long black hair that, when in her way, she would casually put up in a bun by sticking a pen through it. She warmly welcomed the few Westerners that visited Plum Village in those days, and she did what she could to make us feel at home. At that time, she was the only person able to translate from Vietnamese into English or French. When Thay gave a Dharma talk, or when there was an event in Vietnamese, she would sit next to us and translate for hours on end without ever appearing to get tired. Sister Phuong’s way of translating was so expressive that, even after having translated for hours, her voice sounded as colorful as it did when she began.

Three years later, when I moved to Plum Village, I was often the only one during the winter season who didn’t understand Vietnamese. There were about ten of us by then, and after dinner, as we were enjoying countless cups of tea, there was usually a lot of conversation, all in Vietnamese. During those moments, I felt so left out, but when Sister Phuong was around she would always come sit next to me and, while participating wholeheartedly in the conversation, she would translate for me at the same time. I savored those moments in her presence.

She strengthened my confidence that there is always a solution to any problem. One winter, I had promised to make a flower arrangement for a Tea Meditation in the Lower Hamlet. I looked all over and could not find a single flower. When everyone was seated in the zendo and Sister Phuong was about to enter, I ran to her with an empty bowl in my hands, telling her, quite unhappily, that I had not succeeded in making the flower arrangement. Even before I had finished speaking, she picked up some tufts of grass that were growing along the path, added a few handfuls of pebbles from the path we were standing on, picked up a stick lying nearby, planted it in the middle, and . . . voila! Her creation was complete, and the Tea Meditation could begin. While we entered, she gave me a mischievous wink and whispered, “Pure nature.”

As the years passed, more and more people came to Plum Village, and new sleeping quarters needed to be created. One of the places chosen for a future dormitory was the attic of the house where my room was. Cleaning it was a gigantic job, with spider webs from floor to ceiling and the dust of ages everywhere. After cleaning for just a few minutes, I looked like a mineworker. Many hours of scrubbing and sweeping later, I seemed to have made no progress at all. One afternoon, after a few days of lonesome work in that cheerless place, Sister Phuong suddenly appeared, joining me in my work with great swiftness. Her help and enthusiasm were most welcome, but at the same time I felt embarrassed that she was there mopping the floor with me while she had countless other things to do. No matter what I said, she was not at all receptive to my urging that she spend her time in a different way; she continued until the job was done. She never felt that any job was beneath her.

I was often amazed by her inexhaustible energy. If something needed to be finished, she simply continued until it was done, if necessary beyond midnight, without eating and often all by herself. When packages of medicine needed to be sent to Vietnam, she sat for hours on the stone floor, addressing labels and writing uplifting words to each family. Others came and joined her in her work, but when they left she continued. And never have I detected a glimpse of self-pity in her. Despite all she has to do, I never heard her complain that she was too busy. I also never heard her complain of feeling cold, although in the wintertime in the drafty rooms of Plum Village there is certainly reason enough to do so. In early autumn, when I was already wearing two pairs of socks, I saw her walking without any. She never gave the slightest attention to her own discomfort.

During a Tea Meditation, many years ago, I remember her telling us that she had just received a message from Vietnam that a number of artists had been imprisoned. She cried openly as she spoke. I felt so touched. While I suffer from my own pain, I saw her suffer from the pain of others. Far more often though, I saw her laughing, because she is very open to the comical aspects of a situation. Once a small group of very important Vietnamese monks from America paid a short visit to Plum Village. On the morning of their departure, we were all, about twelve people, called to the zendo. We sat in a circle while Thay spoke for a while in Vietnamese. We had just adopted a new routine in Plum Village; when someone was leaving, in order to say goodbye to him or her on behalf of the whole Sangha, one of the permanent residents would practice “hugging meditation” with the parting friend during a communal meeting. Hugging meditation is done in the following way: you first bow to each other, aware of your breath and forming a lotus bud with your hands to offer to the other person. Then you embrace the other person, holding him or her during three in- and out-breaths, fully aware of the fact that (1) you yourself are still alive, (2) the friend in your arms is still alive, and (3) you are lucky to be able to hold each other. Well, that morning Thay asked one of the nuns to come up to say goodbye to one of the visiting monks. In the meantime, he explained to the monk how hugging meditation was done. Only those who know the tradition well can gather how revolutionary Thay was at that moment. It was obvious to us that the monk in question was clearly not accustomed to this form of meditation. And certainly not with a nun! They both stood in front of each other. After exchanging a short, uneasy glance, they started bowing very deeply, and the inevitable happened: their heads collided. It took all of us great pains to refrain from laughing out loud; and like us, Sister Phuong sat for a long time with a twisted face that she just couldn’t manage to get back into the right expression, however hard she tried.

Though countless practical things continuously demanded her attention, Sister Phuong also kept an eye on how we were doing. And if she suspected that something was wrong with one of us, she asked straightaway about it. Whatever it was she wanted to discuss, she always came immediately to the heart of the matter. When I wanted to tell her something, she usually got the point long before I had finished. Her way of listening was very attentive and without judging. When I spoke with her, I always felt a lot of space. Yet I also know from experience that her way of communicating has its own rules, and at times that has been quite difficult for me. The hardest to digest was her sudden way of stopping a conversation—completely unexpectedly, in the middle of a story, in the middle of a sentence. Since I learned that this moment could arrive at any time, I brought up what I wanted to talk about right away, or else she’d be gone long before I’d touched the topic I’d wanted to discuss. And that would be really bad luck. Because she was so busy, you’d never know when your next chance would be.

She could abruptly cut off a conversation on the telephone as well. Just like that. It has happened to me more than once. In the middle of a sentence, I would suddenly hear “beep, beep, beep” in my ear, the connection having been broken. At first I felt really hurt, but as time passed I learned to see that as her “suchness” and to simply accept it as just one of her many sides.

As far as I could see, the contact between Thay and Sister Phuong was very harmonious and without tension. Once, however, at the end of dinner, Thay spoke to her in an unusually stern voice: “Finish your meal!” Because it was so different from how Thay normally spoke to her or to any of us, I never forgot it. There were a few grains of rice (maybe eight or twelve) left on her plate, and Thay further said something like, “Many people are hungry at this moment.” To my surprise, Sister Phuong, with a look of remorse, proceeded to eat the remaining grains of rice on her plate, without any protest at having been addressed that way.

The first year I lived in Plum Village, Thay was the only monastic. But after their trip to India in 1988, Sister Chan Khong, Sister Annabel, and Sister Chan Vi returned with shaved heads—they had become nuns. This unexpected change was a great shock to me. Thay must have noticed, because soon after their return, when I happened to be alone in a room with him and Sister Chan Khong, he invited me to touch Sister Chan Khong’s head to feel for myself how it felt without hair. While I was very carefully touching her head, she laughed at me in a playful way and then took me warmly into her arms and said, “I am not at all different from you, even if I am wearing other clothes and have a shaved head. There is no difference at all between us.”

I felt that something had changed in Sister Chan Khong. I felt the practice had really become number one in her life and that she had made a vow to try with all her heart to live as mindfully as possible. I noticed, for example, that in the middle of a conversation that was getting too noisy, she would become quieter, or while doing something very quickly, she would suddenly slow down. Because I so clearly felt the change that took place in her, it was quite natural for me to start calling her “Sister” instead of just “Phuong.” Speaking about her new position as a nun, she once told me that she wanted to be careful that she didn’t become proud. She explained to me that in the Vietnamese community this could easily happen because, as a monastic, Vietnamese people have the tendency to look up to you very much.

I have always known Sister Chan Khong as a jack-of-all-trades. According to her, she has much less energy than ten years ago, but when I see how much she takes on, seemingly without any effort, I am truly amazed. During a retreat some years ago in a Tibetan monastery in France, Thay fell ill. From that moment on, Sister Phuong took care of every aspect of the program, including the Dharma talk. On top of that, she cooked twice a day for Thay and the three Plum Village residents who had come to take care of the children’s program. In her remaining time, she was available for retreatants who wanted to discuss their problems with her. And when the children’s program didn’t run so smoothly, she took care of that as well. She was the last one to go to bed and the first one to get up, and she continued to be in good spirits.

I have often wondered where her endless supply of energy comes from. I partly attribute it to the fact that she truly lives in the present; from moment to moment she deals with what is coming up, and she doesn’t lose energy in worrying about what may come next, which to me is a reflection of a deeply rooted faith. Even more important though, I think, is her compassion. When she became a nun, she received from Thay the name “Chan Khong,” “True Emptiness.” “My happiness is your happiness” and “your pain is my pain” is something that she truly lives. Seeing the self in the non-self is not a theory for her but the very ground of her being.

REPRINTED FROM I HAVE ARRIVED, I AM HOME (2003) BY THICH NHAT HANH WITH PERMISSION OF PARALLAX PRESS, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA, www.parallax.org.

Eveline Beumkes, True Harmony/Peace, lived in Plum Village for three years from 1988 to 1991. She helped to organize the practice in Amsterdam, Holland and helped translate Thay’s books into Dutch. She was ordained as a Dharma teacher in 1994.