By Brother Phap Sieu

The most common question we are asked as young monastics is, “Why did you become a monk?” I find that I often answer differently. The responses are all true but vary depending on my experiences that day, or who is asking. This process gently reflects that there is no clear stream of events, or even one particular moment,

By Brother Phap Sieu

The most common question we are asked as young monastics is, “Why did you become a monk?” I find that I often answer differently. The responses are all true but vary depending on my experiences that day, or who is asking. This process gently reflects that there is no clear stream of events, or even one particular moment, that opens the way to monastic life. The more I recall, the broader my scope of memory becomes. I must conclude that it is a continual process, which may have begun with a mother’s compassion for her son, extending into the present and onwards. However, there are a few particular memories that shine.

Once during a camping trip organized by the Vietnamese Buddhist Youth Association, two group leaders got into a very heated argument. Just when it seemed they were about to come to blows, the older one announced, “I’m going to breathe,” and promptly vanished into the trees. At thirteen, I waited as long as I could (about five minutes) and then followed. The smiling man, now sitting calmly under a tree, was unrecognizable as the one who had been yelling just moments before. Later he explained that he had learned how to take care of his anger while living in a monastery in Southern France. But the first time I met the Plum Village monks and nuns was completely against my will.

Miraculous Brotherhood

There was no way I was going without a fight. A meditation retreat? At the beginning of summer! But kick and scream as I might, it was fruitless. The agreement was made: if my brother and I were to go for just the week, we would get a whole month of summer to ourselves—no extra-curricular activities, no youth camp, no book reports!

The orientation was boring. How could it not be? One thousand people sitting, watching some monk speak in Vietnamese. I understood about one word in twenty and was too cool (or proud, though I never would have admitted it then) to ask for translation. But the chanting was neat. The bell was pretty cool, too. There was something about how an entire room completely stilled—and if you’ve ever been in a room filled with Vietnamese friends, you know what a feat that is.

It was with the slumped shoulders and defiant eyes classic to many teenage boys that I approached the room marked “Teen Program.” Double-checking my bag to see if my CD player and headphones were on hand, I stepped through the door.

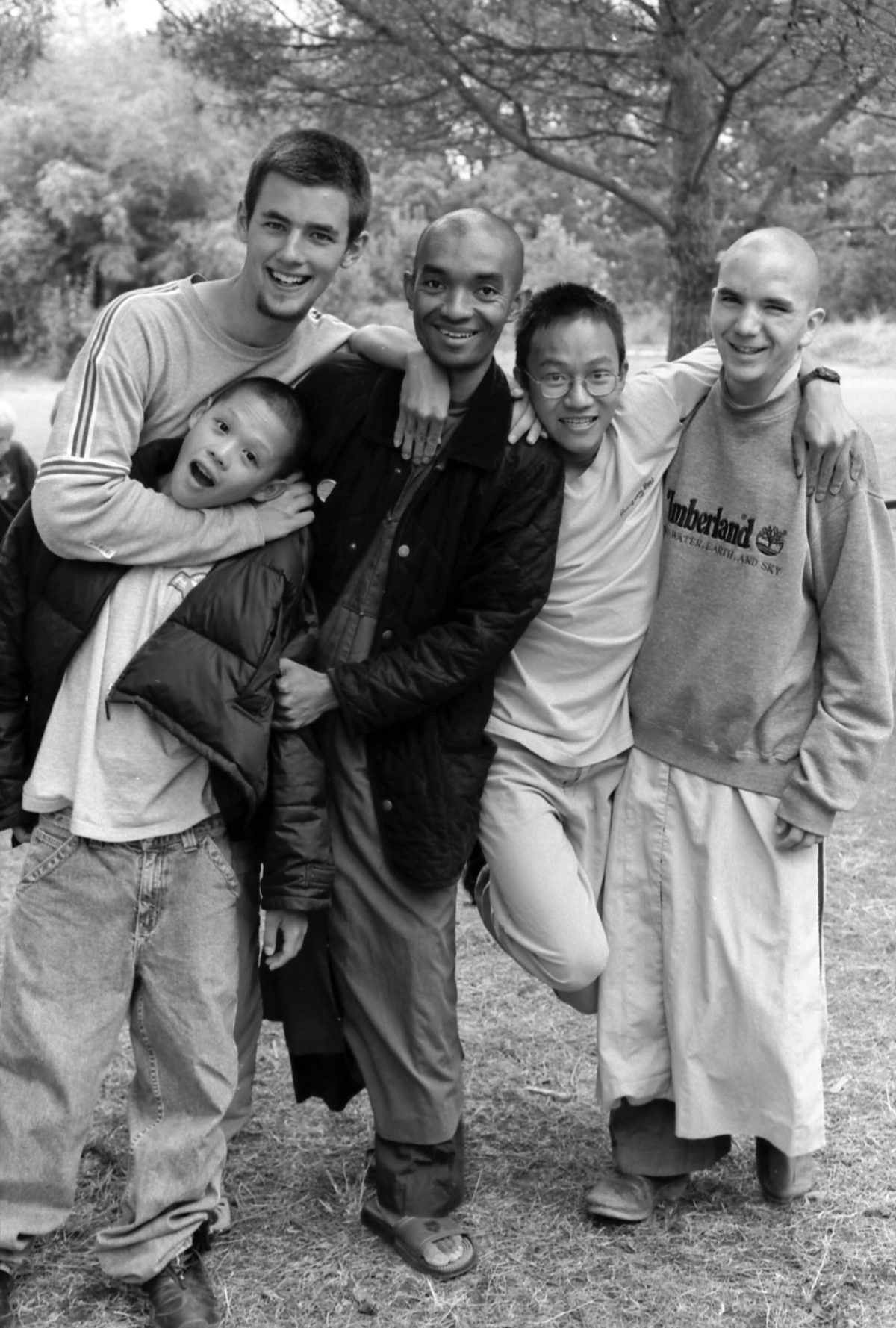

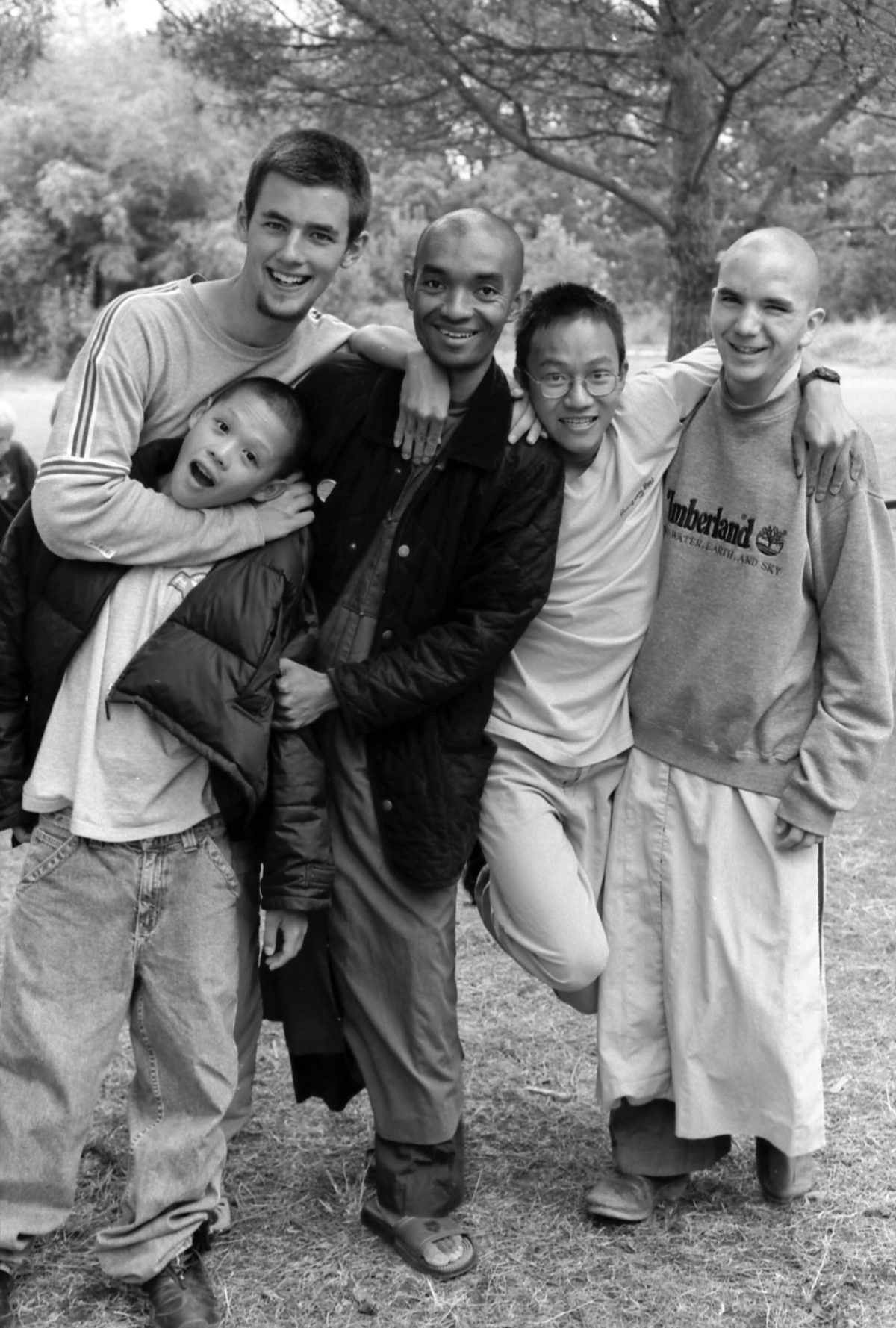

A few days later, one would not have recognized the irrepressibly smiling, glowing young man I’d become. The Teen Program was awesome! Who knew monks and nuns could be so… cool! They even took us to the beach—even rolled up their pants and played in the waves, splashing! But most miraculous was my sense of brotherhood with the other teens. Who could believe that in just five days I could be so open, feel so embraced by these kids whom I’d just met earlier that week? Certainly not me—nor the other teens. It was with continuing wonderment that we shared, laughed, and learned together.

The drive back to San Francisco from San Diego was about eight hours. As we neared our house I woke up briefly. “Mom…I have a question.” She seemed a bit startled; I’d been so quiet most of the trip. “Why did we wait so long before coming to these retreats?”

The Pursuit of Consumption

So tired. That was the thought that followed me to bed every evening, then waited, crouching by the headboard, to greet me every morning. College was everything I had expected it to be, for the first year. That was before having to worry about rent, essays, job applications, clothes, parties, friends, what I would do with the rest of my life. All I wanted was to find a meaningful direction that truly resonated with me. Instead I was taught how to be “successful”: how to make money and keep it. I ignored the happiness of my heart in favor of the calculating logic of my mind. I began to lose touch with the verve of life. Friends began to tell me I seemed down, needed to get out more. Teachers asked about late assignments, and roommates wondered if I wanted to go out Thursday night.

The absence of a spiritual practice and community support was really beginning to show. The Plum Village Retreats seemed ages ago; I was too “cool” now, too mature for singing circles and handholding. There was no way that stuff would work in the real world.

So instead of returning to my body and my breathing, and taking care of my emotions, I partied. At first the partying was filled with real enthusiasm, excitement, and perhaps even happiness. Then the partying became mandatory. Upon meeting friends on campus, instead of “How are you doing?” or “How’s your day?” the common greeting was, “How was your night?” Without enough courage or mindfulness to face the suffering within myself, to stop I was flung headlong into the whirlpool of consumption.

Suddenly I could not wait for the latest movie, book, or CD, could not wait for the next restaurant to open. Life dwindled to nothing but seeking the means to fulfill my need to consume. Later, in my aspiration letter to the monastic community, I likened the pursuit of consumption to a day in an amusement park. Stand in line for roller coaster: three hours; experience twenty-five-second adrenaline rush; get out of roller coaster; get back in line.

Magical Antidote

One day I received a letter in the mail. It was from Mom. Frustrated by my evasiveness on the phone, she finally put everything she felt to paper: all eighteen pages of it. The first three pages expressed concern for my well-being; the following three pages were full of comfort and encouragement. The next six contained detailed charts and graphs depicting just how much my college education cost. The final five revealed a candid account of Mom’s own experience upon first arriving in the U.S.: the humiliating struggle through high school as a complete alien, being responsible for six younger brothers and sisters, acclimating to a completely new continent—all without even the benefit of a common language.

It was a magical antidote for me. Hand-written and drawn, it was a mother’s true love for her child given form. Reading and receiving the contents accomplished what years of consumption, partying, and even counseling tried to hide: I recognized my suffering. I was no longer victim to my own self-pity, helplessness, and apathy. Reading the letter was the beginning of a re-opening of the heart. It also removed any assumptions about the practice being “kiddie stuff.”

Soon afterwards, I found myself driving south to Deer Park Monastery. I continued to visit Deer Park regularly every few months, commuting up and down the California coast, choosing to spend the weekend or spring break there. It was during one of these trips, windows down, speakers blasting the classic Plum Village CD, Rivers, when something clicked. I must have driven up and down the same highway over fifty times at that point, and never had I once recognized the beauty of the setting sun on my left, the soaring mountains on the right. Was there ever anything so beautiful? How could I have driven right by all these years without ever seeing? My heart was filled with a vast and immense joy. In that moment I made an oath to myself to do whatever it took to continue to live fully in the moment, to no longer be blind or deaf to the wonders around me, to life! It was but a small step from there to Plum Village, where the arms of the Sangha enfolded me.

Phap Sieu (Dharma Transcendence) is an energetic monk who loves sharing the Dharma with young people. He especially enjoys drinking tea and playing with the brothers. He resides in Upper Hamlet, Plum Village.