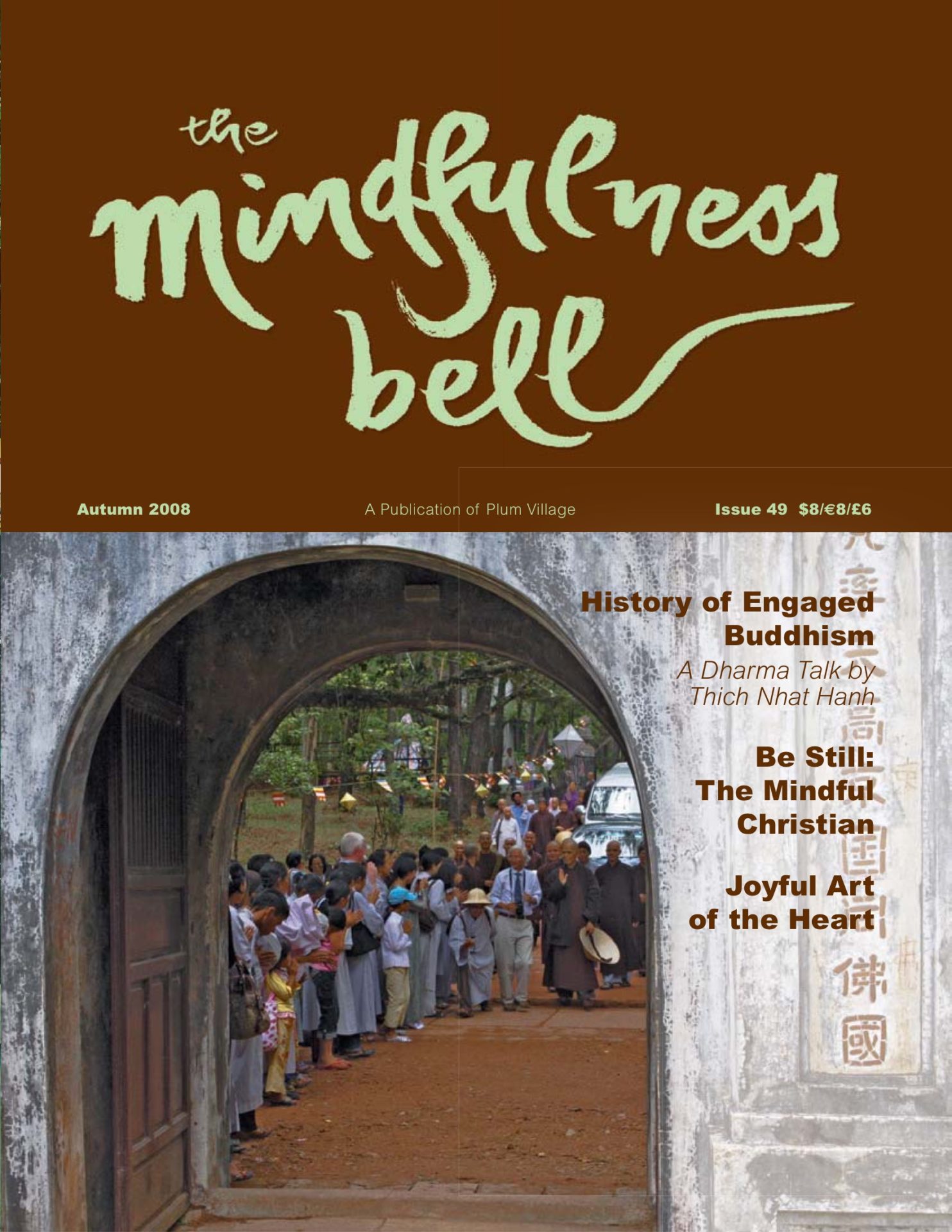

By Jane Ellen Combelic in October 2008

[W]hen the seed of mindfulness in you is touched, suddenly you become alive, body and spirit together. You are born again. Jesus is born again. The Buddha is born again.

Thich Nhat Hanh, Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers

The stone in the ancient church radiates a profound chill,

By Jane Ellen Combelic in October 2008

[W]hen the seed of mindfulness in you is touched, suddenly you become alive, body and spirit together. You are born again. Jesus is born again. The Buddha is born again.

Thich Nhat Hanh, Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers

The stone in the ancient church radiates a profound chill, which the tall propane heaters can barely dispel. Sculpted heads—angels, grimacing demons, and fantastical creatures—glare down from the stark white stone columns, as they have for a thousand years. Though the church is in a tiny French village—on the crest of a hill surrounded by the pastoral landscape of the Dordogne—I am singing a Christmas carol in English along with other Protestant expatriates. My heart is full to bursting with love for the Christ child.

I was invited to the Anglican Service of the Nine Carols by my neighbor Paddy. A British widow, she lives across the street from the house I have rented near Plum Village. I spent the previous summer at New Hamlet and now I have moved back, bringing my dog Serafina with me. In this rental house on a farm near Lower Hamlet, I can have Serafina with me and still attend the winter retreat at the monastery.

The Anglican service could have been cast by the BBC — about one hundred people, mostly British, most over sixty, staid and proper. Their tweeds and dark woolens steam in the tiny church, giving off an acrid and comforting animal scent. The minister, who arrived late, looks the part with his gray hair, white cassock, and smiling blue eyes. But when he starts to speak I can hardly keep from laughing — he has a slight speech impediment and he sounds just like the priest in one of my all-time favorite movies, The Princess Bride. That said, he does a fine job and it is a lovely service.

Paddy, standing all of five feet two in her pumps, sporting a crisp white blouse and gray tailored skirt, is an indomitable force of bustle and cheer known to all. The small choir, with Paddy as its physical and virtual heart, leads us in singing many of my favorite Christmas carols, like “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear”:

Yet with the woes of sin and strife

the world has suffered long;

beneath the angel-strain have rolled

two thousand years of wrong;

and man, at war with man, hears not

the love-song which they bring:

O hush the noise, ye men of strife,

and hear the angels sing.

For lo, the days are hastening on,

by prophet-bards foretold,

when, with the ever-circling years,

comes round the age of gold;

when peace shall over all the earth

its ancient splendors fling,

and the whole world give back the song

which now the angels sing.

Tears roll down my cheeks as I sing and I send gratitude to Thich Nhat Hanh, paradoxically, who brought me back to the faith of my childhood.

A Long Roundabout Journey

My father was profoundly anti-religious and especially anti-Catholic. My mother took on his views but she had been raised Presbyterian and managed to take us to church in New Jersey a few times. Then we moved to France when I was eight years old and my religious education stopped. Somehow, in spite of that, I carried from my childhood a deep and passionate love for the friend I found in Jesus Christ. Then, as a teenager and young adult I turned against it, exploring all kinds of spiritual traditions from the East; after all, this was the nineteen-seventies and that’s what many of us were doing — taking drugs, learning to meditate, listening to Indian music, studying astrology, dancing Sufi dances.

It wasn’t until I was in my forties that I finally came back to the Christian church of my forebears. Many years ago, before I became his student, I remember Thich Nhat Hanh advising Westerners to stick to their own religious tradition. Buddhism, he wrote, can teach us how to live and how to be happy, but it need not replace our religious practices—sentiments echoed by the Dalai Lama. During a life crisis when I needed a faith community, I finally turned to Christianity. And two years before I moved to Plum Village, I officially joined a Protestant church, a very liberal congregation in the United Church of Christ.

At Plum Village I enjoy the chanting in Vietnamese, the simple rituals, the bowing and prostrations. But these practices do not touch the child’s heart in me, they do not bring tears to my eyes. So while I study Buddhism and do my best to put the teachings into practice, I call myself a Christian. How ironic and delightful that it took a Buddhist teacher to help me find my own faith!

Christmas at Plum Village

Ten days after the Anglican Service of the Nine Carols in the frigid little church, I attend my first Christmas retreat at Plum Village.

On the afternoon of Christmas Eve, Thay gives a Dharma talk that opens my heart to the birth of Christ more powerfully than any sermon in a church. In his gentle warm voice, using simple language easy for us Westerners to understand, Thay explains that Buddha and Jesus Christ are both incarnations of the divine, come to teach us the way out of suffering. We look for the Buddha, we look for Jesus Christ, in history and in the world, but where they really are is right inside us. Jesus Christ is being born in my heart on this Christmas night!

On an earlier Christmas eve, Thay gave a similar talk that was published in his book Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers. “Christmas is often described as a festival for children. I tend to agree with that because who among us is not a child or has not been a child? The child in us is always alive; maybe we have not had enough time to take care of the child within us. To me, it is possible for us to help the child within us to be reborn again and again, because the spirit of the child is the Holy Spirit, it is the spirit of the Buddha. There is no discrimination. A child is always able to live in the present moment. A child can also be free of worries and fear about the future. Therefore, it is very important for us to practice in such a way that the child in us can be reborn.

“Let the child be born to us.”

Monastic Vaudeville

After the Dharma talk at Upper Hamlet, Thay returns to his hermitage and the Sangha — all two or three hundred of us — gathers for a festive dinner in the meditation hall. A chilly rain has drizzled all day so we hurry in the twilight and mud, carrying our plates from the dining hall. A true Plum Village feast: egg rolls, fake pork roast made from wheat gluten, olive loaf, vegetable soup, rice noodles, and a lavish spread of delicious Vietnamese dishes I have no name for. Dessert consists of half a dozen sorts of cookies, most of them made with hazelnuts gleaned from a neighbor’s orchard, and apple crumble, also made with gleaned fruit. All made lovingly from scratch.

Fires in the two wood-burning stoves crackle and hiss merrily. The pungent scent of smoke mixes with the smell of damp wool and the luscious fragrance of the food. We linger in small groups, monastic and lay friends, chatting. The sun went down hours ago over the fertile hills of the Dordogne, where all around us in towns and villages and isolated farms, families gather for Christmas Eve.

Finally the time comes for the event we’ve all been waiting for: the Christmas Eve entertainment. (A warning to readers: raucousness, sexual innuendos, cross-dressing monks, and slapstick humor follows. If you don’t care for ribaldry at Plum Village, read no further.)

People new to Plum Village are often surprised to find that every retreat ends with an evening of performances. Monks, nuns and laypeople, especially children, sing songs, perform dances, recite poetry, play musical instruments, or put on skits. On special occasions one is treated to a performance by the Plum Village Players, like tonight.

We sit in a semicircle before a large open space against the long wall. A nun sounds the bell and automatically, reverently, we fall silent.

Then we burst out laughing as onto the makeshift stage walks a bearded Jesus, played by a tall young Western monk wearing a headdress over his bald pate and a shawl over his brown robe. Soon he is joined by his father Joseph, appropriately coiffed in a white towel and also sporting a false beard.

“Jesus, my boy,” says Joseph, draping his arm around the brooding youngster, “it’s time you joined the family business. You’re eighteen, a good worker, and together we can do great things.”

“But father,” replies the teenager, “I don’t think I’m meant to be a businessman. I... I feel I have another calling.”

“Nonsense! Your mother and I have plans for you. You will carry on the family business. I’ve got it all lined out.” Joseph waves his hand in a grand gesture and a big sign appears, carried by two petite Vietnamese nuns: “Joseph & Jesus Corporation.”

We roar with laughter. The play continues as the Devil appears, his face painted in a horrific red mask, his fist wrapped around a cardboard pitchfork. In a series of mini-skits, the Devil tempts Jesus with power, fortune, fame, and we in the audience laugh appreciatively. After all, we recognize this theme; it is one of Thich Nhat Hanh’s core teachings, that happiness cannot be achieved through power, fortune, fame... or sex.

When a tall beefy Vietnamese monk walks out wearing a huge black wig, a blue veil, and a voluptuous bust, the hall explodes in cheers and hoots and gales of laughter.

“Jesus,” s/he coos, “you’re such a handsome young man. Come with me, I can show you pleasures like you’ve never dreamed of.” She bats her eyes, flutters her veil, adjusts her bust, to more laughter and even whistles from the audience.

“Mary Magdalen,” Jesus stammers. “You’re so... so beautiful!” Even he can’t keep himself from laughing.

Naturally our young Jesus comes to his senses. “No!” he says, turning away from her. “I know that you can’t make me happy, any more than power, wealth, or success in the eyes of the world.” Mary Magdalen struts over to the Devil and together they leave the stage, defeated. (Most of us in the audience know, thanks to books like The DaVinci Code, that the much-maligned Mary Magdalen was not a prostitute but perhaps Jesus’ favorite disciple or maybe even his wife. But no matter.)

Joseph reappears from the shadows and Jesus approaches him. “Daddy, I love you very much but I need to follow my own path.”

“That’s okay, son. Your mother and I understand. We know you’ll do the right thing and we support you in being who you were born to be.”

“I love you, Dad!” Father and son embrace and walk off the stage, their arms around each other.

To ecstatic applause the players take a bow, but a resonating bell sounded by the Bell Mistress brings us all back to quiet and mindfulness of our own breath.

I Take Refuge in Jesus Christ

The celebration continues with performances by lay friends and monastics: songs, poems, even a dance by a group of beautiful young nuns. The Plum Village Singers perform the finale: a haunting rendition of “I Went Down to the River to Pray,” the baptism song from the movie Oh Brother Where Art Thou?

Tired, happy, blessed by joy and beauty, we walk out into the frigid night. The rain has stopped, perfuming the air with damp earth and wet fallen leaves. I breathe in deeply. In the distance, ringing from hilltop to hilltop and calling the faithful to Midnight Mass, chime the bells of the village churches.

I remember the Dharma talk earlier in the day, when Thay turned to Sister Chan Khong and asked her to sing a variation on a familiar Plum Village chant: instead of “I take refuge in the Buddha, the one who shows me the way in this life,” she sang, “I take refuge in Jesus Christ, the one who shows me the way in this life.” Her crystalline girlish voice rang through the hall like the sound of angels.

The Christ child smiles, born again in my heart.