By David Ostwald

Sitting awkwardly at my first Sangha meeting in 1998, I was feeling both ill at ease and curious. But by the time we’d finished reading the Five Mindfulness Trainings, those feelings had been transformed to excitement and certainty: I had found my path. One phrase in particular grabbed my attention: “I am determined to make all efforts to reconcile and resolve all conflicts, however small.” It was an intention I was ready to embrace.

By David Ostwald

Sitting awkwardly at my first Sangha meeting in 1998, I was feeling both ill at ease and curious. But by the time we’d finished reading the Five Mindfulness Trainings, those feelings had been transformed to excitement and certainty: I had found my path. One phrase in particular grabbed my attention: “I am determined to make all efforts to reconcile and resolve all conflicts, however small.” It was an intention I was ready to embrace. (This sentence from the fourth training was not continued in the 2009 revision.)

Over the next months, I phoned some people with whom I had conflicts in order to reopen our fractured dialogues; to others I wrote letters of apology and appreciation. I gave a substantial sum of money to an old girlfriend, who in our years together had carried the majority of the financial burden. I thought I was making good progress until a more experienced practitioner quietly suggested that I might also want to apply the phrase to my internal conflicts. A crevasse opened at my feet; I had only addressed the tip of the iceberg.

Old Knots Loosening

In spite of growing up in pleasantly cushioned middle class surroundings with well-intentioned parents, I received my share of wounds. And, like most of us, I developed compensatory behaviors in response. In my case, one of the most potent was taking on the role of the “good boy.” It was remarkably effective at the time, but now, more than sixty years later, it’s become a useless burden. Unfortunately, since my parents have been dead for many years, I only have the mom and dad I have internalized with whom to work out a more healthy and realistic position.

One practice I tried, as a way to shed some useless behaviors, was to close my (almost) daily meditations by offering gratitude to my parents. Sometimes I focused on one parent, sometimes on both; sometimes for something specific—their wonderful curiosity, their trust; other times for something more general—their efforts to be good parents, or just for being who they were. Gradually, over the course of several months, I experienced small heart openings and old knots loosening: appreciation replacing hostility, flashes of anger replaced by understanding.

It was when I wanted to go deeper that I began to appreciate the power of Thay’s insight that we can heal the past in the present. As he points out, not only are all our blood ancestors alive in our very DNA, but so are all our life experiences—including the unresolved conflicts of those who raised us.

As my suffering was lessened by practicing compassionate meditation, I realized that I needed to be in touch with the suffering of the child that I still carried with me. Secure in this understanding, I began focusing on reconciling my conflicts with my mother. Several meditations in Blooming of a Lotus proved helpful, particularly those that encouraged us to look at ourselves and our parents as five-year-olds. Experimenting with the wording of these meditations—for example, choosing different ages for my mother—brought further gains. (I would imagine that for those of us who have stepparents or are adopted, there are probably other fruitful variations.)

Embracing my Inner Child

Another helpful version was offered by Dharma teacher Lyn Fine. She suggested I begin with myself as a one-year-old and then, inhalation by inhalation, work up toward the present: “Breathing in, I am aware of my suffering as a one-year-old; breathing out, I embrace my one-year-old in arms of compassion.” “Breathing in, I am aware of my suffering as a two-year-old,” etc. I have found that some years arouse little or no effect, whereas for others, strong feelings well up. When I experience a “hot spot,” I try to look deeply at the emotions. How many causes and conditions can I discern?

Once, I found myself riveted in fascination when I inhaled “one,” and remembered lying tiny and helpless on an icy rubber sheet. The image was accompanied by feelings of loneliness and profound abandonment. I’m sure my practical scientist mother just laid me down in my bassinet for a moment as she prepared to tenderly bathe me. But wouldn’t someone less self-involved have extended her empathy to understand how vulnerable being left naked on that cold sheet might feel? At the same time, I began to wonder about my own needs. I know my mother was nursing me at that age; why do I not recall the loving warmth of that experience? Is there something in me which cries out, “More…give me more, ever more love?”

Another time, I successfully got by “one” only to stumble into a memory pit at “two,” the year my brother was born. Cradling my feelings, I was able to experience my self-centered, decades-old interpretation that his birth was an act of hostility by my parents. I chuckled. It was a rueful laugh, but I felt freer nonetheless.

Embracing my Mother

Another technique I tried was writing my mom several long and painful love/hate letters. I could only send them by “internal mail,” but it was helpful nonetheless. Ultimately, it was making her hurtful behaviors the object of my meditations that provided real breakthroughs—although not right away. Significant change began only when I acknowledged that she, too, was scarred by suffering; that her suffering was mine, and mine was hers.

Many of my childhood hurts arose out of my mother’s inability to maintain her loving attention for more than twenty minutes. Hundreds of times, I reveled in her warm, loving support only to find myself abruptly “abandoned.” Naturally, like most children, I assumed I was doing something wrong. However, once I was able to embrace her with compassion, I recognized how damaged she was by painful events in her early life, which, of course, had nothing to do with me. How she must have suffered at age nine, when her mother left to be with her lover! No wonder she was fearful of being close to anyone for too long; she might be abandoned again—maybe even by me!

I rejoice in the healing and reconciliation that I am finding through my practice. At the same time, I often feel disappointed; growth seems to come so slowly. I have to remind myself that for every Buddhist story about moments of sudden enlightenment, there are at least as many about dedicated practitioners who sit, search, and question for the better part of their lives. Indeed, even after his enlightenment, Buddha practiced every day!

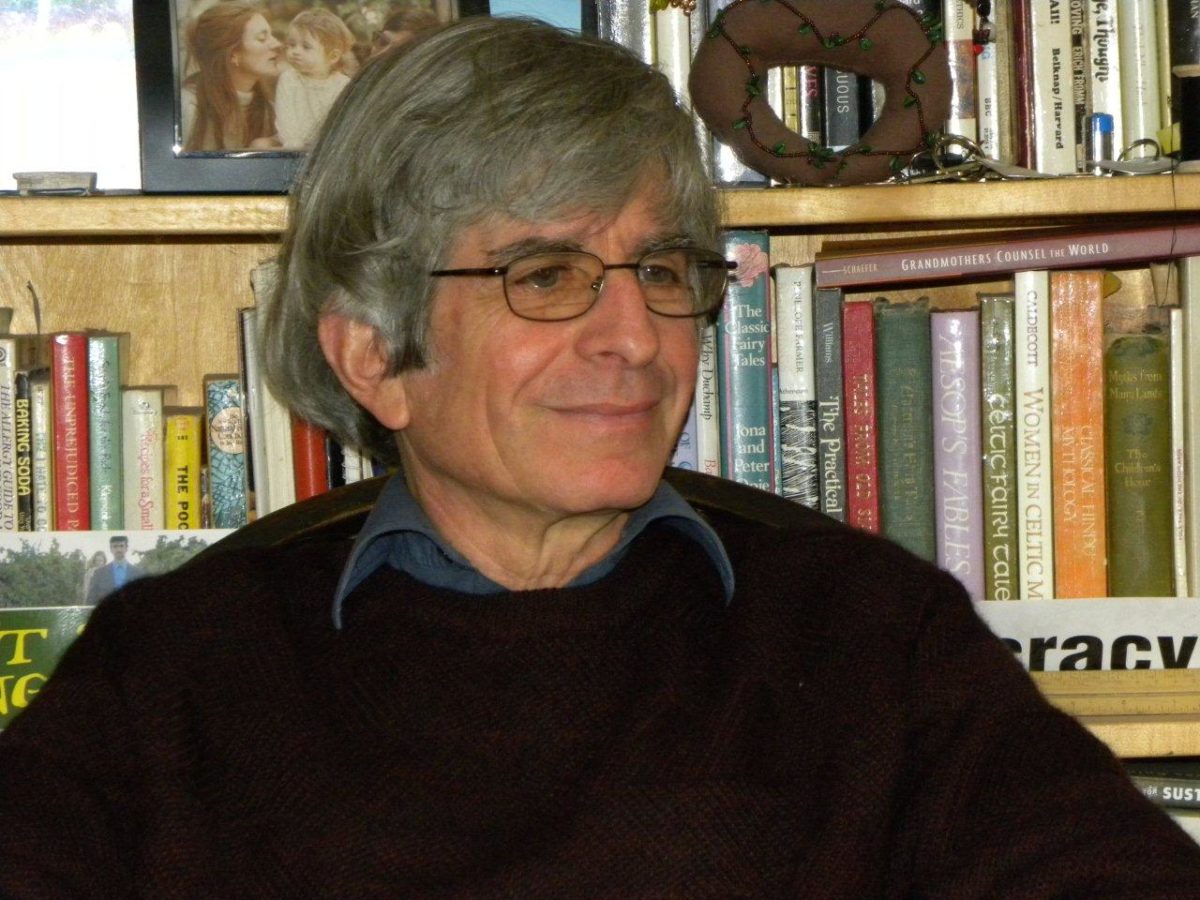

David Ostwald, True Path of Equanimity, has been practicing in Thay’s tradition since 1998. With his wife, Birgitte Moyer-Vinding, he facilitates the Flowing Waters Sangha in Portola Valley, California. David strives to extend mindfulness practice into his work as an opera stage director and as an educator teaching acting to singers.