By Leslie Rawls in June 2000

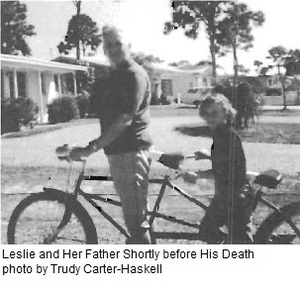

When my father died in the summer of 1965, my world shattered. I was 11 years old, he was 39, and I adored him. In those days, few Americans spoke with their children about terminal illness and death. My parents were no exception. And Daddy’s life hadn’t seemed to change much while he was sick. He went to work every day and was the doctor-on-call each week, though he occasionally slept in a recliner because of pain.

By Leslie Rawls in June 2000

When my father died in the summer of 1965, my world shattered. I was 11 years old, he was 39, and I adored him. In those days, few Americans spoke with their children about terminal illness and death. My parents were no exception. And Daddy's life hadn't seemed to change much while he was sick. He went to work every day and was the doctor-on-call each week, though he occasionally slept in a recliner because of pain. When he collapsed and went to the hospital—to die, as it turned out—we were more than halfway across the United States, on a family vacation during which he'd changed two flat tires. Shocked to my core, I struggled for a long time with the truth and finality of his absence.

Before our father died, my older brother and I had taken increasing responsibility around the house and in caring for our younger brother and sister. Afterwards, my mother relied even more upon us. As I grew to adulthood, I became strong and dependable. I worked hard and accepted responsibility. I sometimes felt I could handle just about anything. Within a short time of meeting me, most people learned that my father died when I was young. I saw it as a badge of strength and independence. Yet, I ached with unresolved grief. I always cried on his birthday and the anniversary of his death, each time mistakenly believing that this last cry would exhaust my well of sorrow. Finally, 31 years after he died, with the help of the Sangha and guided by Thay's teachings, I was able to transform and "resolve" this bone-deep ache.

In the fall of 1996,1 spent four weeks in Plum Village. During the three week "Heart of the Buddha" retreat, I lived in New Hamlet. There, as usual in Plum Village, we formed work families. Our New Hamlet families were all named after fruits. I was in the banana family, and we became quite close. I told many of my new friends about my father's death. During a seemingly unrelated conversation, my banana brother Kees Lodder said to me, "I wonder why that eleven-year-old girl still hurts so much?" I have forgotten what prompted his statement, but these simple words opened the door to my practice focus for much of the rest of the retreat. Over the next few weeks, Kees's deep listening and mindful speech and the support of other Sangha members helped immensely. And Thay's sharing of the Buddha's teachings offered the tools that made transformation whole.

The day after Kees's troubling question, Thay taught us about the Four Noble Truths. The First Truth is suffering (dukkha). The Second Truth is the origin or roots of suffering (samudaya). The Third Truth is the cessation of suffering (nirodha). The Fourth Truth is the path that leads out of suffering to well-being (marga). Thay encouraged us to test these truths through our own experience. With a deep outbreath, I realized how deeply and how long I had hurt. "Here," I thought, "is a real test for these Truths."

Practicing the First Truth seemed easy. Suffering surely existed in me. To practice the Second Truth felt more challenging. It seemed simple to say that the cause of my suffering was my father's death. But starting from this cause, how could I possibly move to the Third Truth—that there is a way out of suffering? There was no way to undo the death. I felt stuck. "Look deeply at the causes of your suffering,"Thay encouraged. "What we first see as the cause may not be correct." I practiced walking meditation on the roads around New Hamlet for hours each day, holding my suffering like a child. Sometimes Sangha friends walked with me. Sometimes we sat beside fields and talked about the practices.

I am somewhat reluctant to share what happened next, for it involves something I can only call a vision—not an ordinary experience for me. I did not consciously beckon or create this vision, but one day, as I listened to Thay's Dharma talk, it came. I was not daydreaming, but in my mind's eye, I saw a tornado dropping from the sky. It did not move across the ground, but stood stationary. Near the top, a face went round and round. I recognized the face as myself at eleven years old. With this vision, I saw that, just as Thay had taught, my original perception about the cause of my suffering was wrong. My suffering arose not from my father's death, but from my own entrapment, my own clinging to all the things I still wished for—to have been a teenage girl with a father, not to be hurt.... I listened to Thay and followed my breath. My mind's eye watched the girl—me—trapped high in the whirlwind. I wanted desperately to get her out.

A few days later, Thay taught us about transforming the suffering of our ancestors and making peace with them. He encouraged us to see our parents and grandparents in every cell of our bodies, in our speech and actions. My vision had not left me, although I did not always focus on it. The girl kept whirling. Thay said to call on the strength of the ancestors in us to transform our own suffering. Putting the teachings into practice, I touched my ancestors, and hoped to gather their strength to liberate the girl in my vision. Each night, I practiced the Five Touchings of the Earth after sitting meditation. One day, in walking meditation beside a rustling cornfield, I tried to free her. In my vision, I stood beside the tornado with my father. "Come on, Daddy. We'll get her down," I thought. I focused. But the girl kept whirling.

"Not enough ancestor power," I thought. So I decided to call on my land ancestors too—the mythological Pecos Bill, legend of the American West. I wasn't sure if myths counted as real ancestors, but he seemed a perfect candidate. At the end of the American tall tale, Pecos Bill lassoes a tornado, jumps on, and rides the whirlwind into the sunset. So, standing at the edge of the cornfield, breathing mindfully, I called with all my heart on Pecos Bill and my father to help me get her down. It didn't work. After fifteen minutes of my conscious breathing and focusing, she still twirled and looked down woefully. I felt defeated.

The next day it rained during Thay's Dharma talk in Lower Hamlet. I sat. I breathed. I listened to Thay and the rain. Then, Thay said, "Practice must be linked to a real problem. Look to see its connection to your life, not as an escape." Hearing this, I saw that the goal of my efforts so far had been to escape from my suffering. I wanted transformation in order to leave the suffering behind. Listening to Thay, I began to feel a deep peace.

The vision did not leave me as peace descended, but it changed. Now, in my mind's eye, I sat cross-legged beside the tornado, following my in-breath and my out-breath. I no longer tried to pull the girl down. I saw that just as my father is present in every cell, this hurt child in a whirlwind is also an integral part of me. As I listened to Thay's Dharma talk, I knew that I didn't need to "save" the girl. I needed to accept her suffering, my suffering, without judgment or blame.

I thought the Third Noble Truth had stumped me, but I had never really practiced the First. Trying to conquer my suffering, I had separated from it, not fully accepting the truth of the suffering itself. After weeks of strong Sangha support, miles of walking meditation, and Thay's transmission of the Buddha's teachings, my heart opened to my own suffering and to the little girl of my vision, and I could offer nonjudgmental love and acceptance.

In the Dharma Hall—as in my vision —I sat and followed my breath. And things began to change. Slowly, the tornado collapsed, ring by ring, like an old-fashioned camping cup. The girl walked to me with a smile. Now, I could accept my own feelings of grief, anger, and abandonment. And I could see, welcome, and love my father in me—all of my father, including his death at the age of 39. Practice transformed the compost of suffering, and joy bloomed in my heart.