By Judith Toy

Faces of the children I work with—victims of great violence and injustice—file through my heart during meditation. What do these children and their families need in order to heal? Only loving attention.

When fifteen-year-old Dee first came to us at the Strengthening Families Program (SFP) in Asheville, she brightened the room,

By Judith Toy

Faces of the children I work with—victims of great violence and injustice—file through my heart during meditation. What do these children and their families need in order to heal? Only loving attention.

When fifteen-year-old Dee first came to us at the Strengthening Families Program (SFP) in Asheville, she brightened the room, chattering non-stop about her training in Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and an after-school program. Dee’s family does not include a father. Because she was in the throes of alcoholism, her mother, Louise, left Dee with her grandmother, who routinely beat Dee with a yardstick. Louise, who had also been beaten, is now in recovery. When she came to us, Louise had only recently regained custody of her daughter and was desperate to re-bond with her child.

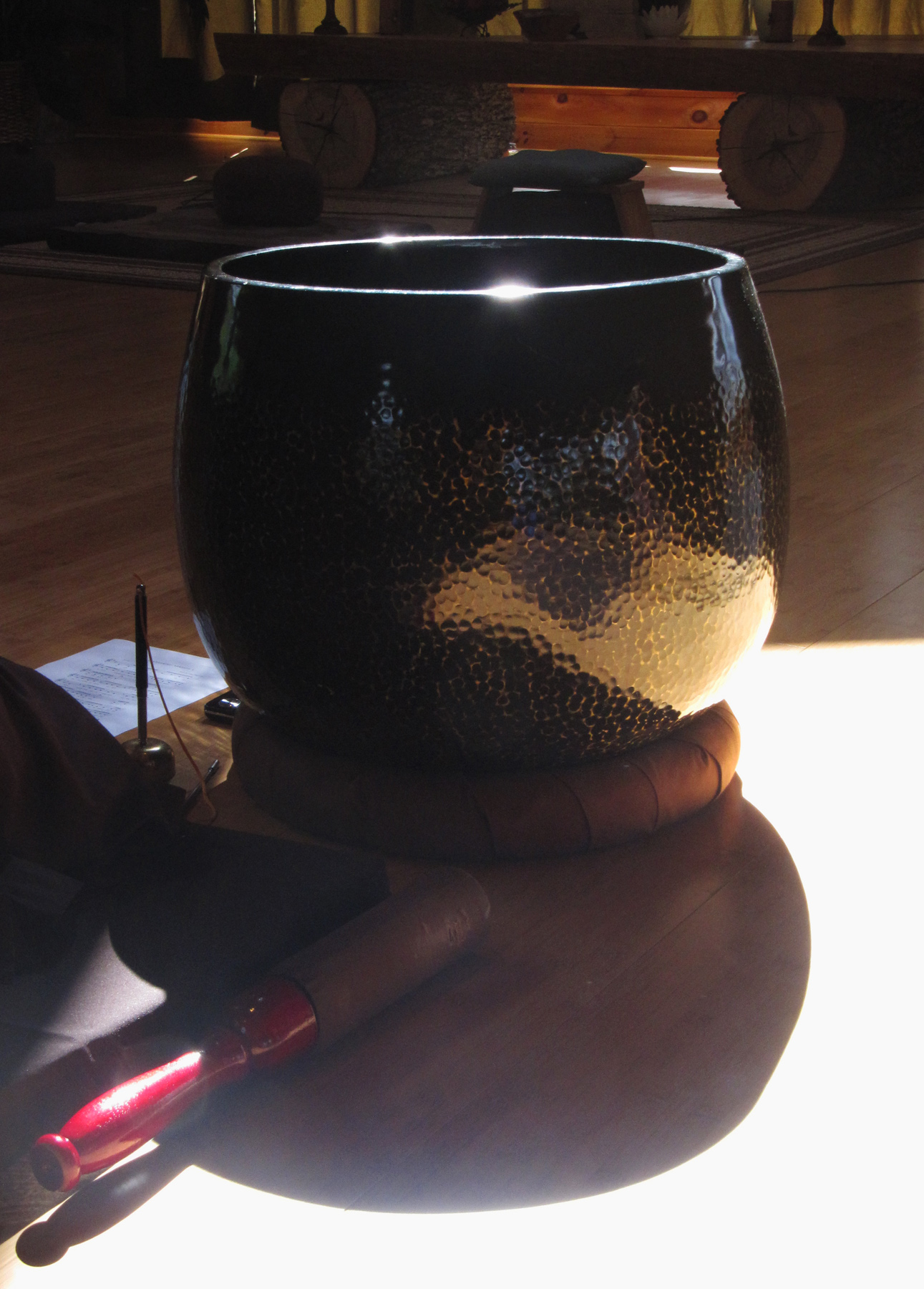

Two Dharma sisters, Susan Hales and I, share an office at the SFP, cherishing the opportunity to realize our ideal of understanding and compassion. Our federally funded program is free to families. Over fourteen weeks, we teach families interaction skills based on a rich, award-winning curriculum. With several staff members on hand to model dinner table conversation, we share a mindful meal, a family ritual which seems to be lost to TV. After dinner—no highly processed food or sugar—children attend class with two youth facilitators. Susan and I begin each class with breathing and stretching exercises. “Breathing in, I know I am breathing in. Breathing out, I know I am breathing out.” Inhalation and exhalation are a kind of prayer to invoke inner peace.

The children learn peer refusal skills, how to identify their feelings, problem solve, and empathize. Their parents—in a separate class with parent facilitators—learn how to better understand themselves and their children, set boundaries and consequences, stay calm, play with their children, problem solve, and empathize. Finally, they learn to help their kids build on their goals and dreams. An hour later, the two groups join a family class to practice what they have learned. Often we use games and artwork to convey deep truths.

Dee and her mother joined this program at a critical moment. There are two times in a child’s life when the brain is completely plastic: ages two and fifteen. This may account for the fact that fifteen-year-olds are often at odds with their parents, because they can see clearly that what their parents say does not mesh with what they do. It is time for them to individuate—to carve out their own values and ethics. This is difficult if the family’s values and ethics are unclear. So, we try to help parents name their family strengths by teaching good seed watering. “Catch your teen doing something good,” we say to parents. And to the teens, regarding their parents: “You can attract more butterflies with honey.”

Mindfulness helped me put myself in Dee’s shoes. What would it feel like to have no father, to lose your mother, to be abused by your grandmother? Through mindfulness, I could model a calm and patient authority for her newly sober mother. One of the ways we guide parents is to help them set boundaries. Time and again, I see kids respond favorably when their parents are able to set firm rules with reasonable consequences and stick to them. Kids interpret this attention as love.

When Louise began to set boundaries, and Dee finally realized she would not be hit if she went outside the lines, Dee pushed them. One evening she arrived with a new piercing—a ring in her lip. Louise had been away on business, and Dee pierced her own lip with a sterilized needle. What delusions needed to be punctured? Louise hit the ceiling when she returned home. She was new to her daughter, and didn’t know how to cope.

Dee was upset at her mother’s reaction, which she said was to throw a loud temper tantrum and lock her out of the house in the cold. I took Dee aside. In tears, and picking at her skin, she told me living with her mother was not working out. She wanted to leave the household and live with her aunt. She was afraid of her mother’s temper. I saw that part of Dee’s fear stemmed from mistreatment at the hands of her grandmother. This is, because that is! In families, we see the flower in the root of the plant. I could see the seeds of rage and dark mental formations that had been carried from generation to generation. Educator and visionary Rudolf Steiner expressed the larger implications of right livelihood with children well: “The way I work with every growing child has significance for the whole universe.”

At a staff meeting, we processed the family problems. To ensure that Louise would continue to attend class and that she did not feel cornered, we decided to set a meeting for her, Dee, and three staff members after graduation, a few weeks away. The happy ending to this story is that by the time graduation rolled around, mother and daughter were reconciled, Louise had learned ways to take care of her anger, Dee had learned that her mother cared enough to set boundaries, and both of them gave SFP an amazing testimonial at the ceremony.

Names and circumstances of SFP participants have been changed to protect the families.

Judith Toy, True Door of Peace, is a senior OI member who, with her husband Philip Toy, guides retreats around the U.S., and this summer, in Ireland and Scotland. They have founded three Sanghas, one in a medium security prison. Judith practices with Cloud Cottage Sangha in North Carolina. She is former associate editor of the Mindfulness Bell.