By Therese Fitzgerald

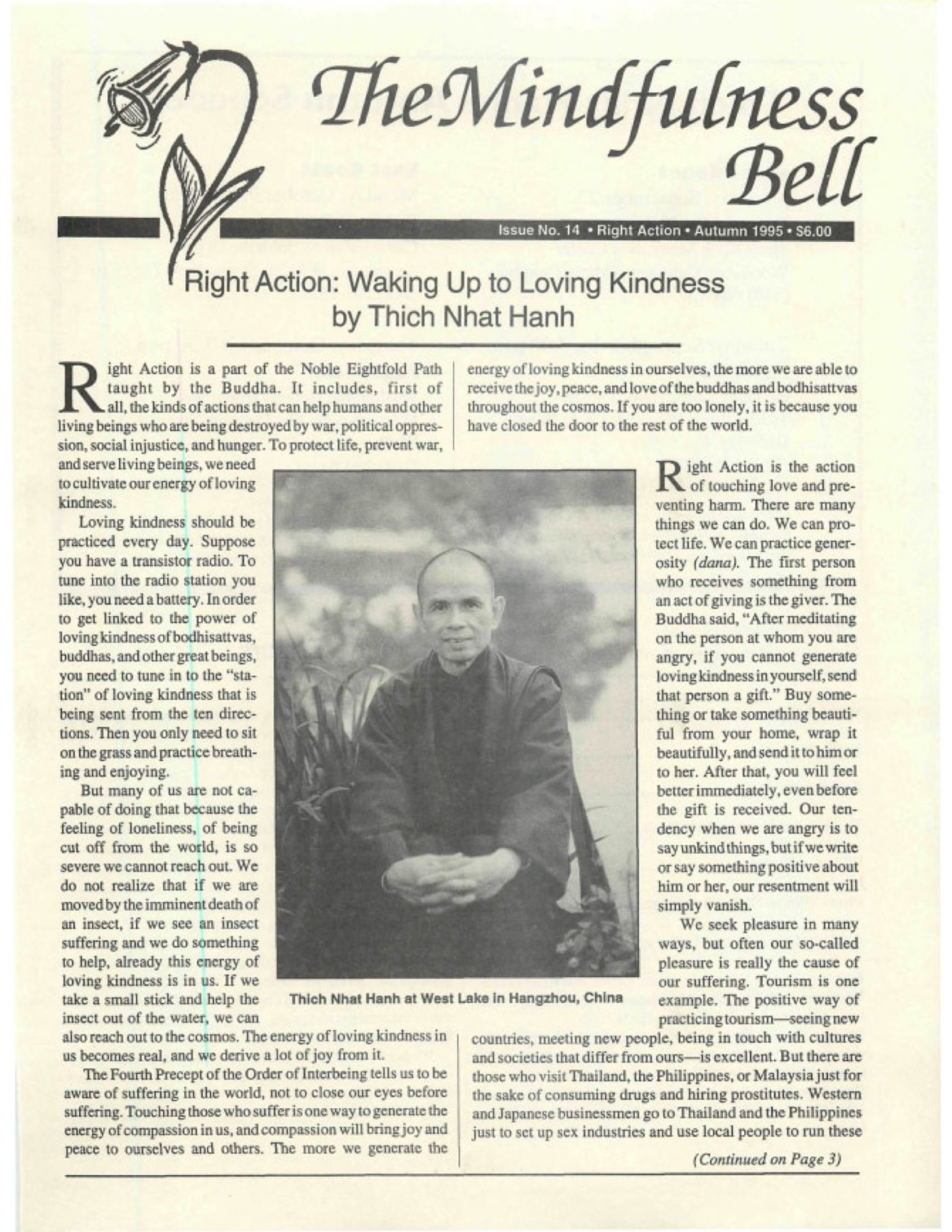

For more than 30 years, Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay) had hoped to go to China to repay the debt he feels to so many generations of Buddhist teachers whose writings and practices were so important to his own formation, by visiting Buddhist temples in China and by offering the Buddha’s Dharma back to the younger generation of monks and nuns there. In the spring of 1995, Thay was finally able to realize this dream. Travelling with seven Western nuns and monks from Plum Village—Sisters Jina,

By Therese Fitzgerald

For more than 30 years, Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay) had hoped to go to China to repay the debt he feels to so many generations of Buddhist teachers whose writings and practices were so important to his own formation, by visiting Buddhist temples in China and by offering the Buddha's Dharma back to the younger generation of monks and nuns there. In the spring of 1995, Thay was finally able to realize this dream. Travelling with seven Western nuns and monks from Plum Village—Sisters Jina, Eleni, Vien Quang, and Annabel, and Brothers Gary, Sariputra, and Doji—Thay and Sister Chan Khong flew from France on March 20 to begin a three-month visit to four countries: Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and the People's Republic of China. Arnie Kotler and I were privileged to be able to fly from California to join them.

For the two years prior to our departure, Sister Chan Khong, Sister Jina, and Arnie had made extensive and detailed arrangements. Thay also agreed to visit Taiwan, Korea, and Japan to lead retreats and give lectures there to help "renew" Buddhism in those countries. Much as Christianity has felt the need for renewal in the West, Buddhism in much of Buddhist Asia has become somewhat stagnant, and Thay's approach that we in the West find so refreshing and new, seemed to our hosts in Taiwan, Korea, and Japan to be the right medicine for the situations there as well.

Taiwan

When we arrived in Taiwan, spring was bursting everywhere. After an hour's drive from the airport through Taipei and then up a mountain at the outskirts of the city, we reached Yang Min Shan Mountain and arrived at our lodging. Walking down the stone steps amid azaleas and blooming cherry trees, with the sound of a waterfall in the background and the sulfurous smell of the hot springs in the misty air, I felt I was in paradise. Our first two mornings, we did walking meditation in the park nearby with the kind family who was allowing us to use their home for nearly a month. A national television news magazine interviewed Thay, filmed our group walking peacefully like that, and a few days later, our walking meditation was broadcast on prime time television throughout Taiwan.

Twenty Buddhist groups had been working together for more than a year to organize Thay' s visit to Taiwan. Under the leadership of Dr. Hsiang-Chou Yo, a lay Dharma teacher well-known throughout the country, the group had planned everything. They even printed beautiful T-shirts with "Thich Nhat Hanh in Formosa" beautifully calligraphed in Chinese, and on the back a list of 100 daily-life situations in which to practice mindfulness. When we met with the organizers, their energetic devotion to helping prepare the ground for and receiving Thay's teachings was inspiring.

Thay's first public meeting was with Master Sheng-yen, the founder of the Chung Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies in Taipei and the Chan Meditation Center in Elmhurst, New York. The two masters bowed to each other and Thay said, "We see in you many generations of Chinese ancestral teachers. We feel gratitude for the teachings passed down to many generations." Then they held a public dialogue on "Chan and Environmental Protection." Master Sheng-yen elaborated on the function of meditation in purifying the mind, and Thay spoke about "mental pollution" and the need to observe carefully the Five Precepts. Forty members of the press attended the dialogue, and dozens of articles appeared in the mainstream press the next day. Torch of Wisdom, a Taiwanese Buddhist newspaper, reported: "[Thich Nhat Hanh's] simple way of practice fits the need of modern people and can be easily practiced in daily living....It is so direct and lively. Chinese Buddhists are caught in metaphysics too much. His fresh air may inspire people. Why should we play at sophistication?"

Then we traveled south by train through lush country by the sea to Hualien to visit the Buddhist Tzu Chi Compassion Relief Foundation and its founder, Master Cheng Yen, "the Mother Teresa of Taiwan." We were met at the station by a team of Tzu Chi staffpeople who ushered us into one of their buses and gave us a thorough orientation, including Foundation songs. At the Still Thoughts Pure Abode Center, a procession met us, and Thay, Sister Chan Khong, and Master Cheng Yen had a semiprivate meeting. After exchanging introductions, Thay asked Master Cheng Yen how she dealt with conflict in the community, and an engaging discussion ensued.

We visited the Tzu Chi College of Nursing, a large campus set among green hills, full of vibrant young women in bright green uniforms. Their well-rounded curriculum includes flower arranging, tea ceremony, and sitting meditation. We enjoyed tea and songs with several faculty members in their refined tearoom. That evening, Sister Chan Khong gave an inspiring talk on "Practicing the Precepts as a Social Worker and Peace Activist." She and Master Cheng Yen communicated their deep mutual respect and quickly became friends. The next morning, there was a large gathering of the local community for a ceremony to distribute aid to the disabled and poor. It was encouraging to see the many forms of "compassion relief practiced by Tzu Chi students—financial and medical, as well as hair cutting, massaging, and simply listening to the stories of the elderly. We learned in detail how the nuns make candles, soy powder, and clay statues for self-support. Passing through the kitchen, we saw gigantic woks filled with food for hundreds of people, and we enjoyed a sumptuous feast of Taiwanese delicacies. This was our first taste of what a vegetarian's paradise Taiwan is. Our visit to Tzu Chi impressed upon us how alive the practice of generosity (dana) is for the Taiwanese Buddhists. People believe very much in giving to monks, nuns, and the temple to attain merit. One-fourth of the Taiwanese people contribute towards the work of Master Cheng Yen, enabling her to give aid throughout Taiwan and the world.

The next day in Taipei, Thay gave a public lecture at the Telecommunications Headquarters to an audience of about 800. He spoke about recognizing the favorable conditions in our life for practicing mindfulness, telling the story of a Catholic woman who practiced mindfulness with all her heart, successfully overcoming severe depression.

The following day, there was a Day of Mindfulness at an elementary school on the mountain with 400 people. I had never seen that many people assemble so smoothly. Everything—mindful movement exercises, walking meditation, lunch—seemed naturally synchronized. Thay's Dharma talk focused on dwelling in the present moment. "Life in the present moment is more precious than gold or dollars. Don't sacrifice your life for the future," he cautioned. At the formal lunch, Thay said, "If we dwell completely and peacefully with the food and the community, we transform this place into Gridhrakuta Mountain or the Jeta Grove." It became apparent how fertile the ground is in Taiwan for Thay's teachings.

In our free time,we visited the National Palace Museum which offered many treasures of China's cultural heritage, including an exhibit of an illuminated manuscript of chapters on Kwan Yin from the Lotus Sutra. Many exquisite paintings of Kwan Yin further strengthened my affinity with her. We ended up spending as much time enjoying oolong tea and aduki bean pastries in the grand tearoom as we did looking at the exhibits. We also had time to receive acupuncture treatments from a doctor friend of Dr. Yo's. It was amusing to see a dozen of us stretched out holding our limbs up with needles sticking out every which way!

On several occasions, we experienced the strong support given to monks and nuns that is so integral to the collective consciousness of the Taiwanese people. The laypeople have high expectations of the clergy and vigilantly protect them. For example, if a monk were to buy a cake containing meat, the vendor would inform him that there is meat in it, concerned that the monk bought the non-vegetarian cake by mistake. And vendors often refuse to accept money from monks or nuns and just give them whatever they want. Taxi drivers often give monks and nuns rides free of cost.

We travelled by bus from Taipei to Taichung, in central Taiwan, enjoying the Taoist temples nestled in the lush, misty mountains, the green rice fields, and many gardens of bananas, palms, papayas, eggplants, and strawberries. Thay led a Day of Mindfulness with 400 people at a newly-built temple located high above the city of Taichung, famous for its gigantic wooden fish drum (mokugyo) and brass bell.

We were greeted at Chung-tai-shan Monastery by the fragrance of orange blossoms and very balmy air. The next morning, we had breakfast with the kind, elderly abbot of the temple, Master Wei Chueh, one of the great Chan masters in Taiwan.

Sister Chan Khong gave an evening session for nearly 100 novice monks and nuns, ages five to fifteen, complete with jogging meditation! Sister Annabel and Arnie gave public lectures in Taichung on the practice of mindful living that were well received.

The next morning, we visited the Hsuan-tsang-szu Institute of Buddhist Studies, a sprawling campus. The senior monks asked TMy basic questions with great sincerity, and Thay led a lovely walking meditation in the mist. We spent the afternoon at Sun Moon Lake in a thick fog and enjoyed walking through a temple together and learning about Chinese pilgrim Hsuantsang, who is said to have carried the Tripitaka from India to China in his backpack. Then we stopped in a tea shop operated by "aboriginal" Taiwanese. The tea was delicious and we exchanged songs in English, Madarin, and Taiwanese with the shopkeepers, whom, it turned out, recognized Thay from a TV feature on him that had aired a few evenings earlier.

A highlight of our visit to Taiwan was a seven-day retreat at Pao Lien, a Pure Land Buddhist Temple in Chungli, about an hour from Taipei. Master Kwan Hsin, the dynamic abbot and his community of monks and nuns worked tirelessly to accommodate us and the 400 people who attended the retreat. In fact, the abbot and his monks and nuns joined us in many of the practices over seven days.

During the first Dharma talk, Thay said there was "no line separating Pure Land Buddhism from Chan (Zen, or meditation) Buddhism." He presented mindfulness as the "mother of concentration and wisdom," and spoke about being present and real for our loved ones, outlining the "Six Miracles of Mindfulness"—to be present, to make the other real, to relieve the suffering of others, to stop and calm ourselves, to look deeply, and to transform ourselves. In speaking about the "Four Nutriments"—edible food, sense contact, intention, and consciousness—Thay presented teachings about looking deeply into suffering and seeing the "food" that fuels our suffering in order to bring about liberation. He also outlined the Buddhist understanding of seeds of consciousness bijas) and emphasized the need for the practices of the Peace Treaty and Beginning Anew.

During Dharma discussions, retreatants expressed how the teachings and practices were being experienced. Topics from discovering the smile, to marital problems stemming from families separating to give children schooling abroad, to wives whose husbands gamble or have mistresses, were explored with great gusto. The benefit of Thay's teachings in renewing Buddhism and giving people practical ways of understanding and transforming the realities of their lives was very apparent.

The teachings of Thay and the practice of prostrations brought people in touch with their roots and allowed for deep transformation to take place. One Taiwanese bhiku told us that thanks to the practice of prostrations, he was able to transform his deep conflict with his father and become a free person.

On the last day of the retreat, we were joined by 600 laypeople from the nearby community for a Rose Festival. Women in traditional white dresses offered each person a red or white rose, representing their living or deceased parents, respectfully. The statements about filial relationships moved everyone to tears, including the abbot. The translator had to pass the microphone when he became overcome by emotion. It was a beautiful and powerful ending to our time together. After a festive lunch, the sun shined through the clouds, after seven days of rain.

Our Day of Mindfulness at a high school gymnasium in the southern city of Kaoshiung was also attended by 400 people, including 35 children. People here were especially inspired by Thay's fresh, applicable teachings. They found the practice of the Five Prostrations reaffirming of their connections with ancestral teachers and family and the land of their birth. One Chinese bhiksuni revealed that although she had been a nun for twelve years, it was only after hearing Thay's Dharma talk that she felt truly liberated from her suffering. We ended the day with an Infinite Lamp Ceremony. It was lovely to see Thay begin the lighting of the battery-powered "candles" and watch as the whole room became a sky of twinkling stars. "The lamp continues from one to another and becomes everlasting," Thay said, "to remind us of the importance of making our life the Dharma and passing on the Dharma."

Travelling back to Taipei from the south by bus, we passed ancestral shrines facing every direction amidst rice paddies, corn, papaya, strawberry, and sugarcane fields, lotus ponds, bamboo groves, duck farms, chicken coops, occasional clusters of traditional brick buildings with tile roofs and courtyards, ornate Buddhist and Taoist temples, three-storey concrete apartment houses, and huge concrete and gravel factories. Spring continued to unfold as leafless trees produced orange, magnolia-like blossoms tucked on the upper branches like baby doves.

Our last days in Taipei centered around three evenings in the elegant Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, including two public lectures by Thay and a Five Precepts ceremony for more thanl,500 people. We especially enjoyed the opening performance of modern Buddhist songs by a chorus of young people. On our last day in Taipei, Thay led a Day of Mindfulness for 1,200 people.

Throughout our stay in Taiwan, our practice was permemted with the singing of the Chinese version of "Breathing in, Breathing out," kindly translated by Shyang Jen, our host in Taipei, who took care of our meals and transportation, and "I Have Arrived," translated by Nancy Kuo.

Before leaving for the airport, we had an important meeting' with local organizers, during which Thay emphasized mindfulness practice while organizing. Dr. Yo, John Chang, and others expressed their hopes that Thay or some of his students return to Taiwan regularly to help the wonderful seeds of Dharma grow steady and strong. We expressed special gratitude to Dr. Yo and all those who helped him make our visit so pleasant and fruitful.

Korea

Five years ago, Ok-koo Kang Grosjean had the idea to translate Thay's books into Korean. She found a publisher, Buddhaland Publications, and Being Peace and The Heart of Understanding became bestsellers there. When Ok-koo learned that Thay would be visiting, she and Mr. Hyung-Kyun Kim, Buddhaland's pub-lisher, invited him to come to Korea to teach.When we arrived in Seoul International Airport, we were surprised to see three TV cameras recording Thay's arrival. In fact, our whole ten days in Korea were filmed by MBC-TV and then broadcast to 4 million people after we left. We were whisked off in black cars across sprawling Seoul to Chung An Temple, where Reverends Wan Taek and Won Myong, who work with Mr. Kim publishing Buddhist books, greeted us. After bowing to the Buddha and chanting, we sat down at a long, low table and enjoyed a feast of mountain vegetables, varieties of kimchi, special wild mushrooms, spring herbs, and traditional Korean desserts. After strong ginseng tea, we continued on our way to the Korea Christian Academy House outside Seoul, that was chosen for its natural beauty, fresh air, and quiet, for Thay and his entourage to stay.

On our first morning in Korea, I rose early and hiked up White Cloud Mountain, enjoying the fresh, cool air of another spring in Asia, fragrant with magnolia and azalea blossoms, listening to various chanting and singing by the passersby, and marvelling at hikers dressed in brightly colored sun visors, long socks over their trousers alpine-style, and parkas.

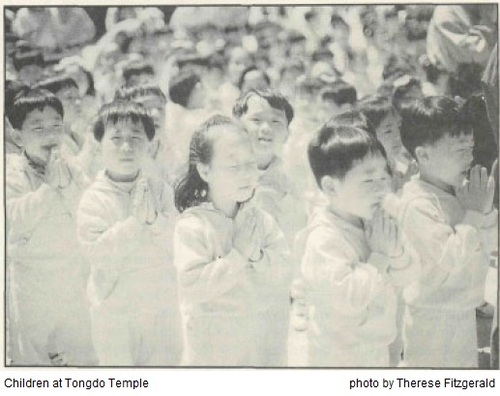

That evening, after a two-hour drive, Thay gave a public lecture to 1,000 people in Taejon City, sponsored by Pop Dong Social Welfare Buddhist Institute, an urban nunnery and kindergarten run by Chong Sil Sunim, the abbess of Cha Kwang Temple. The evening program began with 20 little boys and girls dressed in brightly-colored traditional robes circumambulating Thay while singing a Buddhist song to piano music. Smiles turned to joyous laughter as the children continued around and around until the adults were finally able to coax them off the stage. Thay's lecture focused on harmony in the family. The abbess of Cha Kwang Temple later told Thay that listening to his Dharma talk was like listening to a deep and beautiful poem.

The next morning, before Thay's public lecture at Dongguk Buddhist University, we looked across at the hillside full of blooming forsythia, and then at the bell tower surrounded by cherry trees raining sweet blossoms, and felt the beauty of being together with Korean practitioners in their beautiful country. During the talk, Thay asked, "How is a Buddhist university different from a non-Buddhist one?" He depicted the Buddhist university as Maitreya, the Buddha of Love—the students as the arms, and the teachings and practice of love as the heart—"a center of love, the body of the Buddha recognized by the whole country. A Buddhist university should teach the students how to love—love ourselves and love one another—in order to be happy. Professors have to prove they have the capacity to love and to understand. Enrolling in a Buddhist university, I would want to be sure that the professors are able to transmit the art of loving and understanding. There should be good communication between the students and the professors. The professors should be able to listen deeply to the suffering of their students. Wisdom and spiritual values from many generations are the greatest teachings to be given to the students."

The next morning, Thay gave a public lecture in Chogye Temple to 500 mostly middle-aged and elderly lay Buddhists, along with a number of monks and nuns. After listening to choral music reminiscent of American gospel music, Thay spoke about compassionate listening and loving speech: "Bring space into your and the other's heart. True love always brings freedom and happiness. Mindfulness helps us examine our true situation and stop and transform our suffering."

In Seoul, we also visited the Lotus Lantern Temple, where Thay gave a Dharma talk to a very crowded room of Westerners.

That afternoon, after a slow drive across the city in bumper-to-bumper traffic, we arrived at Koo Ryong Temple for a televised interview with renowned Buddhist poet Ko Un. To Ko Un's question about Thay's involvement in the peace movement, Thay emphasized the necessity of "making peace within ourselves and thereby establishing harmony between members of a family, between Christians and Buddhists, and between North and South." When questioned about "producing what we don't need and losing traditional values," Thay pointed out that "Buddhist mindfulness alerts us to the pollution of our consciousness" and proposed such practices as "selective television viewing" as a practice of self-protection, and warned against "eating meat and drinking alcohol as unkind acts towards those who are starving." To Ko Un's question about the population explosion, Thay recommended "helping people with education and means of exercising family planning." The TV film crew had already stopped when Thay and Ko Un exchanged intimacies: "You feel to me like an ancient Korean poet monk," Thay said, •and Ko Unsaid that reciting a poem chases away evil spirits and recited one of Thay's poems. That evening a few of us attended a celebration for the publishing of Thay's Old Path White Clouds, Miracle of Mindfulness and The Diamond That Cuts through Illusion in Korean, as well as Ok-koo's new book of essays.

The next day, Professor Hyun-kyung Chung, a Christian feminist liberation theologian (who has been to Plum Village and taught at Harvard University), interviewed Thay and Sister Chan Khong for Dialogue, the largest academic Christian magazine in Korea. In response to Professor Chung's question, "Why a new order (the Order of Interbeing)?", Thay described himself as a monk in the traditions of Lin Chi Zen and the Order of Interbeing as a "new branch of an ancient tree, a bridge between the lay and monastic communities, an important instrument for responding to difficulties and anguish of the world (engaged Buddhism)." Thay emphasized that "church leaders need to renew practice to respond to the needs of the young people, and help Buddhists make peace with their own tradition."

Sister Chan Khong added, "I was half a hungry ghost as a young person, admiring everything modern and Western about French culture. My cultural roots were weak, but my family roots were strong. The peace and joy in my first teacher, Thay Thanh Tu, attracted me to my root tradition. He radiated peace, but he did not explain Buddhism well, and his answers did not satisfy me. Thay Nhat Hanh explained in a very profound, nondualistic way, and I began to feel the desire to become a 'thoughtful tiger,' dealing with negative 'habit energies,' anger and strongheadedness, making a constant effort to transform myself through my work in society." Professor Chung spoke about the tendency of original sin in us—"Can we really trust in the potential understanding of each person?" Thay responded: "If you doubt the seed of understanding and love in everyone, you doubt God. Understanding is the power of liberation, and the lack of understanding is the cause of suffering. The practice of meditation is looking deeply in order to understand.' Love is the force of liberation,' Martin Luther King said. 'Love your enemy' sounds funny unless you can understand him or her. Understanding is the key to love and acceptance."

Professor Chung brought up self-immolation as a radical expression of the longing for peace—"a ritual among student movements in the '70s and '80s in Korea." Thay emphasized motivation as the crucial point—"the willingness to restore understanding and compassion and alleviate suffering, rather than the desire to destroy"—and pointed to Jesus on the cross and the life of Gandhi as examples. "It is the truth that liberates, so communicating the truth is the most important thing. In Vietnam, more is known now between the North and the South. In Korea, too, if Buddhists and Christians in the South can understand each other better, that will help the North. True understanding of the truth is the key to liberation. And our work is to make the truth available based on the practice of looking deeply."

Professor Chung said that in liberation theology there is a tendency to think of God as "opting to side with the poor." Thay responded, "The rich suffer too. God operates with the highest understanding and embraces the rich and the poor. Work for social justice should be done without taking sides. You have to find the causes of oppression and do the right thing to help transform the situation. Dualistic ways only strengthen suffering. Love and understanding are our best 'weapons.'"

To Professor Chung's quote, "Hope is exiled," and her question, "What is your source of energy?" Thay responded, "Faith in the practice, not in ideas, can bring joy and happiness. Faith is a fruit of the practice that that no one can remove, not even theologians."

Later that afternoon, Thay gave the keynote address to a group of thirty Catholic, Protestant, and Buddhist leaders gathered for an "Interfaith Dialogue for Peace" organized by the Korean Christian Academy. Rev. Pyon Sun-Won introduced Thay, saying, "The cross and the lotus should be comrades in the face of suffering." Thay spoke about "how to coordinate our light arid energy to better serve the world. All of us have suffered betrayal and misunderstanding from people in our own tradition. So dialogue needs to go on within our own tradition. If you understand your own tradition, you can understand another tradition well. We need to transform ourselves to become instruments of love. We need to make peace within ourselves, be the King ruling over our territory, our five elements. But we resist. The pain is too great."

"People need Jesus; Jesus needs other people in order to manifest. Before bringing an offering to the altar, be sure you are reconciled with your brother or sister."

We did walking meditation in the misty afternoon, and after a silent dinner, we heard responses from the participants. One nun related that during walking meditation, as worries and thoughts about her self-centered practice assailed her, she heard a voice say to her, "Jesus Christ, look at the cherry blossoms. It is your image reflected here." One man spoke about transforming "righteous anger" into transformation of society, and "inner peace too easily attained." Thay responded, "This reveals that you are more a philosopher than a practitioner. Inner peace is not easy to attain. To not be aware of children dying of hunger is not to practice mindfulness. It is to be a rabbit hiding in its hole." A monk spoke of walking meditation as "the synthesis of Zen and social action" and presented the problem in Buddhism of emphasizing wisdom more than compassion: "Understanding the word is the priority in Korean Buddhism. Quietness of the holy one is not so useful; abstract compassion not so helpful." Thay spoke about "compassion as the flower born from understanding," and then he ended the dialogue with these questions, "Can someone have two different spiritual roots? Could you sponsor a marriage of two people of different traditions? Could you encourage the two to develop both roots?"

Early the next day, Thay met with descendants of the Ly Dynasty of thirteenth-century Vietnam. When the Ly Dynasty, one of the most benevolent and intelligent, was overthrown, Prince Ly Long Tuong left his country by boat and took refuge in Korea. He and his friends and families were welcomed by the Emperor of Korea, and for more than 30 generations, the they and their descendants have been assimilated into Korean culture. Now, one Ly Dynasty prince named Ly Xuong Can is attempting to touch his Vietnamese roots, and he was joined by several other family members for tea with Thay. Even though their interest seemed to lie in details about how to preserve the shrine of the Li Emperor, Thay related to the seeds of yearning in them to know their Vietnamese cultural and religious roots. He spoke about the peaceful, loving nature of the Li Dynasty; how socially conscious they were in exercising understanding in making judgments of criminals and how they cared for prison inmates. Thay made concrete suggestions about convening a family gathering and listening to the needs and experience of the young people; meeting again and having the parents calmly express their difficulties, as the young people need to understand; deep listening between husbands and wives; and lastly, how most of our perceptions are wrong perceptions and what trouble that can get us into in relationships. On our bus ride south to the Kong Rim Temple in Choong Chung Province, we passed through "seas" of black plastic waving in the sunshine covering crops, fields of ginseng covered by strips of black fabric, peach orchards, terraced rice fields with rock walls, traditional houses with blue, red, and green tile roofs, Christian missions dotting the countryside, bright green mountains, and wide green rivers.

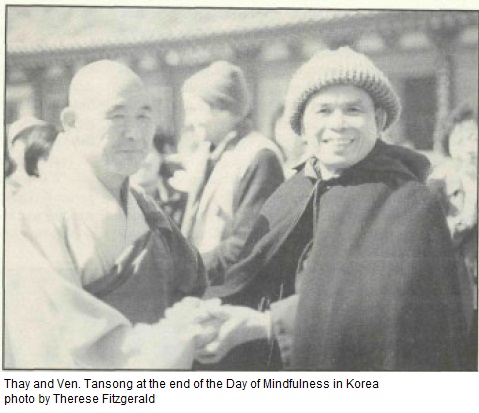

In a meeting with the abbot of Kong Rim Temple, Venerable Tansong, who had served as administrative head of the Chogye Order, Thay said, "You are here like the roots of the ancient tree. We in the West are like the branches. We admire your courage and determination and freedom from attachment to fame and position, as, after the reformation, you returned to the monastery to practice and share the Dharma." The abbot responded, "If we practice deeply and keep the precepts, we will spread the Dharma well." Smiling, he added, "The reformation (in Korean Buddhism) happened thanks to many clergy members and laypeople. It is because of my lack of ability to manage the Order, not because of courage and determination, that I came back to the monastery. Vietnam and Korea have similarly been divided because of ideologies, and I have appreciated the work of Thich Nhat Hanh throughout." The day-and-a-half retreat was enjoyable and meaningful for the participants, including many intellectuals, writers, artists, scholars, and peace activists.

That afternoon we went by bus to Baekryunam, a subtemple of Haein-sa (Reflection on a Calm Sea Temple), one of the three main temples in Korea, representing Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. This subtemple was the home of the late Venerable Sung Chul, who was the head of the Chogye Order before he passed away last year. While he lived there, anyone who wished to see him had to prostrate 3,000 times before the Buddha first. Reverend Won Taek, Sung Chul's chief disciple, welcomed us. It was marvelous to step out of the bus and feel the deep silence and solitude of this remote subtemple perched on a mountain. In the morning, I climbed up to a piney spot and enjoyed watching the gray morning turn golden as the sun rose. After breakfast of white rice, vegetables, and pickles, we headed off for the main temple, Haein-sa.

The abbot of Haein-sa thanked Thay for planting seeds of the Dharma all over the world. Thay responded, "We are only the seeds and flowers. You are the roots," and he spoke of the importance of renewing Buddhism and speaking in a language that young people can understand and relate to. We were given an extraordinary tour of the building where the entire Korean Tripitaka, consisting of 81,340 wood blocks, is kept.

Afterwards, we traveled to the nearby Po Hyun Am (Samantabhadra Nunnery). We became absorbed in looking at the various buildings, when Thay reminded us that we should go to the main temple and pay our respects and make prostrations. "No bowing, no eating," he said, and we all smiled. Indeed, we were served a scrumptious vegetarian feast, ending with a lovely pink dessert. After lunch, we headed southeast to Kyongju City, the old capital of the Shilla Kingdom, where we visited the stone grotto, Suk Kul Am, and the beautiful, huge stone Buddha. This city is like a museum, featuring the famous Pul Kuk Temple with two pagodas, and Nam San Mountain that contains several hundred rock-carved Buddha images.

In Kyongju City, there was an impromptu discussion, during which Mr. Kim said, "What the clergy teaches is not what people need." Thay asked, "Who can help renew Buddhism in Korea, laypeople or the clergy?" Mr. Kim: "There needs to be cooperation of both. Renewal of lay Buddhist organizations is already happening. How to really practice is the question. How to develop educational programs to spread authentic practice? Most laypeople don't know about authentic practice. They only want blessings. The clergy is involved in esoteric, extreme practices." Thay suggested that the Korean Sangha send a few young people to train at Plum Village.

One of the highlights of our time in Korea was our visit to Unmun Nunnery in Kyung Buk Province. As often happened throughout Asia, as soon as we entered the grounds of the nunnery, a feeling of peace and loving care was felt through every detail of the place and people. Here, 300 nuns practiced meditation, studied sutras, learned how to care for children's education and attend the elderly, and practiced cooking, cleaning, and gardening in mindfulness. The Buddhas there were feminine (without moustaches). In the morning, Thay gave a talk to the nuns in one of their classrooms.

Later we went to Tongdo Temple. We visited the museum and then were allowed in to see the stone stupa where the relics of the Buddha are kept. Thay and the monks, then the nuns, and then the laypeople were invited into the special parlor of the abbot, Venerable Wol Ha, the newly elected head of the Chogye Order, to visit with the abbot's assistant. The two masters exchanged calligraphies—Thay's in English, "There is no way to happiness. Happiness is the Way," and the assistant abbot's in Chinese: "The Tathagata Buddha of Infinite Lifespan/Limitless Life Thus Come Buddha."

We traveled by bus on to Pusan on the southern coast, and that evening the Buddhist Broadcasting System sponsored a lovely dinner, during which Thay commented, "It is because we were co-practitioners in former lives that we are sharing a meal tonight." Thay gave a public lecture that night sponsored by BBS radio, which 1, 000 people attended. Mr. Kim introduced Thay, remarking on his "childlike face and presence, purity, clarity" and how "great difficulty makes for a great personality." Thay spoke about practicing mindfulness in order to be present for our loved ones and about how "Buddhist meditation, in the deepest sense, is to remove our notions of happiness that can be an obstacle to happiness. There are so many ways to create happiness, you should not restrict yourself to only one way." Thay also encouraged "rediscovering the jewels of your Buddhist heritage....We can produce cars and computers, but we have not been able to produce enough mindfulness. We have made great developments in telecommunication, and yet communication is weak between family members, between Christians and Buddhists, between North and South."

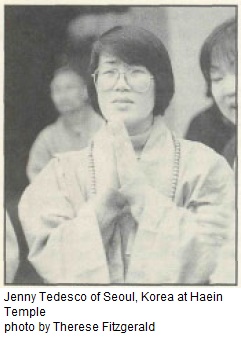

Our last night in Seoul, after a most delicious dinner at Jung Soo Am Nunnery, served by the abbess, Sang Duk Sunim, we had a Sangha-building meeting. Mr. Kim proposed that he print a small booklet about Thay's teachings and a 20-page article in a popular Buddhist magazine. The TV program on Thay's visit to Korea, which was broadcasted in May after we left, turned out to be a great resource for the Korean Sangha. Professor Chung proposed holding an afternoon of mindfulness to help a core group of mindfulness practitioners to develop. Frank Tedesco suggested that there be a network with foreigners in Korea through the mailing list of retreatants and others who attended lectures by Thay. Sister Chan Khong said, "Mr. Kim reminds me of the young people in Vietnam who work so humbly and profoundly and devote their whole life to the Dharma." Thay said, "Many seeds have been sown, and many more will be sown through the television program, videos, and books. Still, some work needs to be done to help these seeds spring up. All of us should practice. No one should only organize."

Our time in Korea was short, only ten days, and we had only a brief retreat program, but we could see through our contacts that Thay's teachings are very useful for Korean Buddhists and Christians. The thirst for spirituality juxtaposed with the economic boom in Korea makes for fertile ground for the teachings of the Buddha as presented so vitally by Thay.

Japan

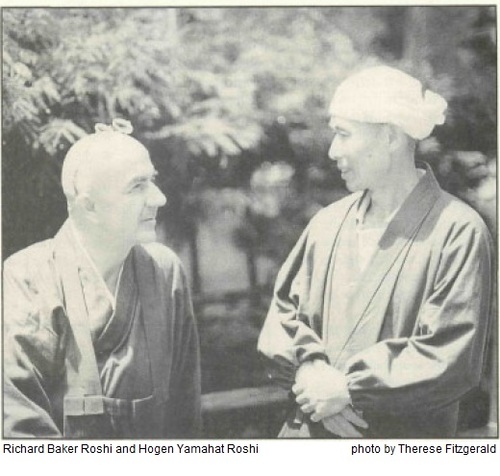

How marvelous to arrive in the Osaka Airport and discover yet another spring. We were greeted there by a hardy team of local organizers and practitioners, notably Tamio Nakano, Keisuke Shimada, and others of the "Web of Life/Mindful Project" organization. Kaz Tanahashi, Richard Baker Roshi, Issho Fujita, and the Hunt-Badiner family also joined our group here. At a meeting that afternoon with reporters, Thay said, "Driving through Kobe, I was breathing deeply, aware of the suffering experienced through the earthquake. When the tragedy occurred last January, I told my students in Plum Village that the teachings of the Buddha stress impermanence, and that the best thing to do in response to this tragedy is to accept each other, reconcile with each other, and love one another in the present moment, or it may be too late. In the time of the Buddha, catastrophes were believed to be reminders to live a noble life. I believe this practice and belief have to do with the Buddha's understanding of collective karma. People need to consult wise people in the country as to how to take care of the country." Sister CMn Khong added, "I understand your suffering. Life seems fine, then suddenly, like in the war in Vietnam, friends are killed and life seems turned upside-down. Peaceful villages suddenly collapse. Nothing can prevent catastrophes. The only way to protect ourselves is to live a life of beauty and goodness, so that good energy will envelop us and protect us."

There were questions about Thay not being able to return to Vietnam, to which Thay responded, "I am in this position because I was not aligned with any party during the war but I spoke out for the people caught between the warring parties. My books and tapes are now being widely circulated in Vietnam. I feel I am there now. I believe in a few years I will be able to go back, as things are changing." Smiling, he added, "Also impermanence."

The reporters noted that many Vietnamese in Kobe are still living in temporary shelters after the earthquake. "What words of consolation do you have for them?" they asked. "Tragedies usually come double, one after another. Goodhearted people can be aware of their plight and help the victims. "

There was also a long discussion about city people losing a sense of connection with the earth, and the growing interest in ecology stemming from this threatening sense of alienation. Thay responded saying, "It is very hard to see the moon in the city. That is regrettable. People are so busy. They lose contact with nature and get sick. They feel a void and fill themselves with things that pollute their body and their consciousness. It is the duty of the media to warn people about the need to practice mindfulness in order to avoid the pollution of consciousness by newspapers, television, and so on. Buddhist teachings can help us change the situation and protect the environment of the heart and of nature. Plants, animals, and inanimate objects all have Buddha nature. The Buddhist teaching of non-self is that man is made of non-man elements. If we destroy non-man elements, we destroy ourselves."

One reporter commented on the variety of Thay' s approach to Buddhist teachings, noting genres such as poetry, ecological writing, Dharma teaching, and fiction. Thay responded, "We owe so much to the Buddha whose teachings are simple, not metaphysical but practical guidance for real problems of our day. People have made these teaching too complicated. Personally I have been able to transform my suffering, anguish, and fear, and to get in touch with refreshing, wondrous, and healing elements of nature. My happiness is an outcome of that practice and that allows me to help others. That is why I think it is important to rediscover the simplicity of the Buddha's teachings and help young people with their real problems. Buddhism is at the foundation of Japanese culture. Jewels are there, perhaps buried under layers of time. For example, I have discovered that the Diamond Sutra is the essential teaching of the Buddha for protecting the environment. Japan has realized technical success, and we know that that does not guarantee happiness. We can look to the Buddha's teachings for happiness. It's time to go home, to get in touch with our spiritual roots. I asked someone, 'Are many people becoming monks and nuns in Japan?' Their negative response disturbed me very much. If there aren't people devoted to the happiness of many people, society will suffer. That would be a loss."

Later that afternoon, a few of us went with Thay and Sr. Chan Khong to the area of the temporary shelters for the Vietnamese victims of the earthquake. This was an appalling sight—people crammed into uninsulated tents and makeshift structures. Needless to say, people were very grateful to have Thay visit and see their plight directly.

The next day, Thay gave a public lecture in a beautiful auditorium in Osaka to some 1,100 people, emphasizing "realizing the Pure Land as our heart," recognizing the conditions in our lives for happiness, being present for our beloved ones and the nourishing elements in our lives (the moon, the blooming magnolia tree). "True peace and happiness is impossible for one who is running and believing that they are to be attained sometime in the future." He dwelled on practical methods of practicing the Dharma to restore communication as a family: "Pain and anger in us cause us to get agitated and react. We need to practice mindfulness and deep listening with each other and take mutual responsibility for the growing negativity in a relationship. Transforming, not blaming, is the solution. Looking deeply at our suffering helps us see the way out."

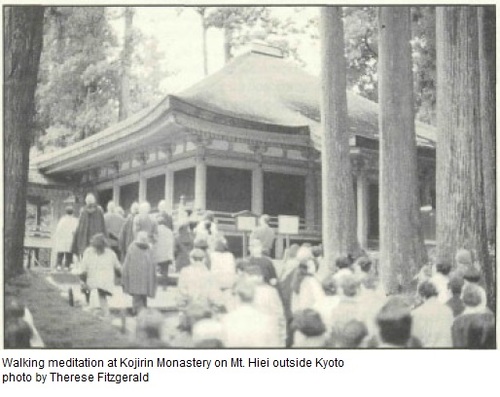

That night, we arrived in the thick mist at Kojirin Monastery on Mt. Hiei outside of Kyoto and enjoyed being in the middle of a great coniferous forest. We arose at dawn for a Day of Mindfulness with 125 people.

A meeting the next day with priests and one nun at a cabin on a wooded hillside right in Kyoto was a powerful way to get to know their situation. "Most priests are the sons of priests who were very busy," they said. One priest said, "I hated the Buddhism that was passed on to me. We have no private or contemplative time. But my father's temple needed me to succeed my father. I didn't understand the strange relationship with parishioners. It was very heavy for me to be treated as such a special person. I did not feel deserving. The 'beginner's mind' of the American Buddhists appeals to me more, so I decided to take a sabbatical and go to the United States to practice." Thay asked if people consult the priests about their difficulties, and the priest answered that they do, but he did not know how to help. "Being a priest," he said, "is more a profession than a religious endeavor. The priests in Japan are not service-oriented. They serve the dead, not the living." One Zen master said that those at the top speak about "non-realities. They are not addressing real problems, and the people who are concerned about real problems have no power. Anyone up high does not dare speak out because of the delicate connections between religion and politics." Anotherpriest described things this way: "Buddhism is out of shape. Superiors are always giving splendid advice, but there is discrimination based on gender, seniority, and social status, and the discrepancy between these problems and the Buddhist teachings to live in the present and look into our own hearts is too great." People discussed the lack of response from temples in the case of the Kobe earthquake, and then a discussion about addressing nuclear energy problems ensued. "If temples in Kobe cannot help earthquake victims, how can they help stop the proliferation of nuclear energy?" Thay queried. "The sect headquarters should give the order to the various temples to take in a certain number of families made homeless by the earthquake."

Thay said, "Unless a monk is happy and free, he cannot help others. There needs to be space within and around him. The idea of married priests is not a bad idea. But to stop the tradition of celibate monks and nuns completely is a bad idea. The Buddha and the monks of his time cherished freedom and time for themselves. As a monk, you leave family and enter a new one. To me, a monastic community is a real family. If your monastic family is not happy enough, transformation will not be possible. A monastic family has the right to exclude someone who may need more than the community can give. A monk or nun who leaves the community does so because the community is not happy enough. If you can communicate with your teacher and Dharma brothers and sisters, you don't feel the need for a private family. We have to invite each member to speak the whole truth, as long as they do so with right speech.

"We are very aware that beginner's mind is precious for monks and nuns, and we take are not to let it erode away. At Plum Village, we allow more time for the practice than for studies. Four years of training provides a strong base for practice in daily life. It may be possible to help as a couple, but it is easier as a monk or a nun. We have to try our best to make monastic life as happy as possible, each person accepting the other as he or she is.

"The gap between Buddhist studies and practice is too great. The studies are advanced, but they don't address real problems—take, for example, the gap between the 'sound of one hand clapping' and one's anger and difficulties. The first Noble Truth must be addressed. The fourth Noble Truth must respond to the first truth.

"Our Japanese friends may try to practice both the 'happiness of one person' (being a married priest) and the 'happiness of many persons' (being a celibate monk or nun). The Order of Interbeing, inspired by the bodhisattva ideal, is composed of monks, nuns, and laypeople. The Order bridges the gap between the monastic community and the world. The monastic community is more informed about the real problems of the world.

"To have a temple is to have a family. To have two families at the same time can be very difficult. In the United States, not many people trust monks and nuns. The clergy has somehow lost their spiritual leadership. When people have problems, they go to psychotherapists."

Thay asked questions about the bhiksu and bhiksuni tradition. "More and more priests do not want to take care of temples. How are we going to solve this problem?" The priests described the problem of private ownership of the temples. Thay said, "In China and Vietnam, monks have the power to decide the fate of the temples. But the lay followers influence the clergy. They expect the clergy to behave, or they boycott them. For example, if they eat meat or drink alcohol, those monks will lose support." One priest responded, "The Japanese laypeople don't have great expectations of their clergy." "It is a matter of mass education of the laypeople," Thay said.

We held a four-day retreat at the main center of the Shishinkai Sect that follows the teachings of the Lotus Sutra, in Isehara, Kanagawa Prefecture, near Mt. Fuji, for 150 laypeople, including 10 children. Thay's teachings focused on the "four mantras" as a practice of love according to Buddhist teachings, and misperceptions and pride as the greatest obstacles in realizing that love. He also devoted some time to the "purpose of Buddhist meditation, that is, cutting through the vicious cycle of suffering transmitted to us by previous generations"—dealing with anger and other negativities by "embracing them non-dualistically with the energy of mindfulness and transforming them." "Every mental formation touched by mindfulness can change," Thay said, reassuring and encouraging us. He taught methods of "unilateral disarmament," reconciling with or without the other.

The local organizers, many of whom have been students of Joanna Macy, requested that one evening be devoted to "American Mindful Living," in the form of a panel of Baker Roshi, Kaz, Arnie, and myself. Arnie began with a calm overview and established some basics about the community of Buddhist practitioners in the United States. I spoke personally about my inspiration to practice meditation from an inner and engaged perspective. Baker Roshi spoke about being and not being an American, and Kaz concluded with a description of the work of Plutonium Free Future and Japan's production of plutonium. The evening ended with a young Tendai priest crying with distress and shame at his country's naming the two nuclear power plants "Monju" (Manjusri) and "Fugen" (Samantabhadra), the bodhisattvas of wisdom and action.

The walking meditation practice at this center was splendiferous, as the azaleas were in full bloom, and the greenery was lush and sweet. One of the children noted "13 different varieties of azalea." Discussions in small groups were great vehicles for expression and sharing for people perhaps not so used to it. The children enjoyed themselves, even though they were too shy to display it in front of the large group most of the time. The cooks were macrobiotic and the meals dependably interesting, and healthy.

We arrived at the Tokyo Grand Hotel as guests of Sotoshu International, energized and ready to face the noise and congestion that greeted us on the streets of that huge city. I enjoyed hours and hours of exploring side streets full of noodle shops, bakeries, and everything imaginable being produced and sold.

Thay's public lecture to more than 1,000 in Tokyo, sponsored by Sotoshu International, concentrated on the establishment of real understanding and love as an antidote to the growing phenomena of "hungry ghosts," especially as they manifest in the form of strange sects. "Violence and anger are symptoms of the lack of love and understanding within, even though they are enacted in the name of a 'religious vision or revelation.' It is a fanatical act borne of violence, hatred, and ignorance."

At an interview after the talk with Yomiuri Shibum, a large daily newspaper, Thay emphasized Buddhist practice as effective means to address real-life problems. "Such koans as 'Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?' must be practiced in a way that can help liberate us from our despair, fear, and anger."

The next day we headed west to Kiyosato near the Japan Alps for a four-day retreat at the Keep Foresters Camp. Thay's teaching dwelled on "arriving home at our true nature in the here and now." '"Have a good day' may be only a wish. We can make our day good with conscious breathing. When I first encountered the Sutra on the Full Awareness of Breathing, I felt like the happiest person in the world. I have been a happy monk for over 50 years. If I have been able to help others be happy, it is thanks to the practice of conscious breathing."

Thay spent most of the Dharma talks instructing people how to practice "love that is not just an intention but a real capacity to make the other person happy," warning us that "acting in the name of love without understanding could be destructive to your loved ones."

Imagine our joy at the end of the four days of rain, fog, and cold mist to wake up the last day of the retreat to a clear blue sky and full look at snow-covered Mount Fuji rising above the other mountains! We had an especially long walking meditation after the lecture on "no birth, no death" that morning, and we were so happy to be outside in the bright day. The retreat was so deep that many participants kept stopping each of us to thank us. One Zen teacher and yogi came to Sister Chan Khong and asked her to transmit to Thay his deep appreciation for "the greatest gift of wonderful teachings. In particular the prostrations helped me transform deep and hidden pain in me."

We said farewell as the other retreatants were settling down for lunch in the dining room of wooden picnic tables. I remember thanking the macrobiotic cooks for their wonderfully tasty, nutritious, satisfying meals. Because of the long walking meditation, our group was unable to stay for lunch, as we had to catch the train to Kamakura to prepare for the Day of Mindfulness there. At the train station, we witnessed the strange seizure experienced by one of the Vietnamese retreatants. Later that night in the lovely Komyo-ji Temple in Kamakura, our host, Tamio-san, learned of the tragedy that had befallen the other retreatants after we left.

One of the cooks had meant to gather a particularly delicious wild herb for the soup, but had inadvertently picked a poisonous one that looked almost exactly the same. Within minutes of eating the soup, the 60 retreatants who were having lunch began to feel the effects. At first their vision became lucid, then they lost vision. Following that, they lost use of their limbs, and finally, they collapsed and vomited, some for hours. All but two people were rushed to the hospital.

For the next 24 hours, we were all on pins and needles awaiting reports from Kiyosato about everyone's health. Tamio-san and Brother Doji drove there that night, and the next day, Brother Doji, with letters from Thay and Sister Chan Khong, visited more than 60 people in four hospitals. As the reports trickled in, we felt more and more hopeful: people were recovering and eventually everyone was released from the hospital, fully recovered.

All of the Kiyosato retreat participants expressed gratitude for being alive and for the practice of mindfulness and Sangha that helped them enormously during their ordeal. One woman woke up during the night in the hospital and began to sing Thay' s poem "Call Me by My True Names," and her roommate joined her. They described to us later the amazed look of the nurses seeing these patients singing joyfully in the middle of such a difficult night. Another woman wrote to Thay, expressing her thanks for the powerful experience that helped many people measure the depth of their practice after the lesson of no-birth, no-death that morning.

But in Kamakura, we were unaware of the outcome as we began our Day of Mindfulness Sunday morning, Mother's Day for 400 people. Later, Thay said, "We all acted as one Sangha through this tragedy. Everyone tried to support each other. There was no blaming, no suing. The event was a strong bell of mindfulness. We have to rejoice that no one among us is dead. This is the most enjoyable thing. We have grown up and become stronger, and we have benefited from the experience. Maezumi Roshi died yesterday in Tokyo. We almost met with him there. His death is another bell of mindfulness. He was strong and healthy yesterday. If we have anything unresolved with anyone, we should resolve it or it may be too late. Those who recovered from the food poisoning have learned to practice well in the face of adversity."

Sister Chan Khong reflected, "Looking deeply into that event, why did we, the team accompanying Thay, escape the accident? We had some merit, yes, but a rather humble merit, not enough to protect our 80 friends. The fact that we escaped the accident may be thanks to the merit of the 400 Japanese friends who attended the Day of Mindfulness in Kamakura who deserved to receive Thay' s wonderful teachings that Sunday. If we all went to the hospital, how could they have had that chance to practice the Dharma? It also may be thanks to the merit of the Chinese people who deserved to receive Thay's teachings. If we had gone to the hospital, our China trip would probably have been cancelled. So the patriarchs in China protected us from that accident, so that the trip could be possible.

We had a second meeting with priests and others in Kamakura the next day to discuss the future of Buddhism in Japan. Thay opened the session by saying, "We have come from far away, and we don't know much about Japanese Buddhism. Please tell us about your aspirations and hopes for Buddhism in Japan. Please tell us about your happiness and your difficulties. Our time is a time of adaptation. Christianity, Judaism, and of course, Buddhism need to renew themselves."

The first speaker was very critical of institutional Buddhism: "We are not interested in the future of Buddhism. We care about the future of human beings. Japanese Buddhists don't think much about their response during World War II. Monks and nuns don't pay attention to the difficulties of poor people. Only a few Japanese Buddhists are interested in the difficult situation of Buddhism in Burma and Bangladesh. If the Buddhists would reflect on the past, maybe then we could discuss the future. Look at the homeless in Tokyo's Shinjuku Station. Can Japanese Buddhists go to such places and show their care? Christians do join in the work being done here to protect the rights of the homeless, not the Buddhists."

A monk said, "Our rich society is losing its spiritual life. Japanese Buddhists only want personal, individual happiness. There is too much institutionalization and people caring only about problems about property maintenance, and position of power; too little bodhicitta; no real Sangha. My pessimistic view is that without a Sangha of all different sects in Japan, there is no future for Buddhism here."

There was some discussion about women and Buddhist practice. Thay and Sr. Chan Khong spoke about the "invisible practice" of nuns in Vietnam and Taiwan practicing the Pratimoksa and doing humanitarian work. In response to the feeling that the clergy serve only the dead, Thay said, "This practice is needed too. When we pray for the dead, we create peace in our heart. It serves both the living and the dead. But because we ignore the real suffering of people, they don't come to our temples when they have real problems. We have to ask the children, the families, and others in society what kind of suffering they experience. Then we will be able to offer them ways out of their suffering. A good Buddhist knows his or her own suffering and tries ways to alleviate it. He or she can then share what has been learned. If we come together and see how to address real problems, we will create a Sangha that is very interesting, and people will come back to us. Monks and nuns and elder brothers and sisters in the Dharma should offer their happiness to others. That will speak most eloquently, and they can help people know how to practice. We need to restore the capacity of spiritual leadership and authority, not just as scholarship, but as practice—the living Dharma.

"Here in this temple, I have been able to touch the spiritual heritage of Japan. Many young people came to our Day of Mindfulness yesterday. They are there, ready to practice. You only need to offer them a chance."

There was an amazing demonstration of Noh drumming by a sixteenth-generation artist, and then we all enjoyed a marvelous box lunch.

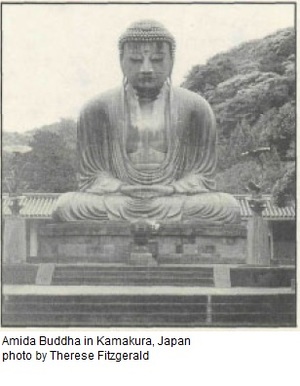

Our last morning in Kamakura, we visited the Great Buddha (Dai Butsu) and were invited into the private garden there. Our last evening in Tokyo, we had a farewell dinner and a Sangha-building gathering. The time with the wonderful Japanese Sangha came to a close for now, and we were off to China.

China

Flying from Hong Kong to Beijing, the sun spread out like molten gold over the glistening rice paddies. There was some feeling of magic in the air as we approached the long-awaited fulfillment of Thay's dream to visit China.

China was the only country that we visited where there were no local Buddhist hosts (for obvious reasons). But we were certainly hosted in China—by our national guide, Hibiscus, and by a local guide at each location. Hibiscus and Peter, our Beijing guide, were waiting at the airport to greet us and escort us through the crowds and traffic to our hotel.

The first morning, Thay called us all to his room and told us, "We can share the practice the world over. Take each step in mindfulness here in China. We can bring light to Chao Chou's Bailin Temple, where we will meet the master in the abbot. I am so grateful to Chinese Buddhism. My books being translated into Chinese (in Taiwan) makes me very happy, as I feel I can give something back. Economic growth is not enough. Happiness is based on spiritual life. We rely on masters to practice spiritual leadership." ThSy cautioned us to refrain from discussing political topics. He said, "We may not be able to share our practice on this trip. Maybe the only thing we can share is our mindful steps. Please practice mindfulness every time you walk outside of our bus. Keep silent and walk mindfully with joy and peace. That will be powerful enough."

We made a short visit to the Temple of Heaven, built in the Ming Dynasty, originally a site for harvest and atonement rituals. There was amarvelous moment when one of the guards peered with great curiosity at Sister Jina, pointed to her own sky-blue uniform and then at Sister Jina's eyes and exclaimed in Chinese, "I've never seen a blue-eyed Buddhist before!" We did walking meditation through apark of cedars back to the bus.

We were asked not to walk in Tianamen Square as a group, because it might look like a demonstration, but Sister Jina and I went and walked around the Monument to the Peoples' Heroes and the Mao Zedong Mausoleum with the awareness that thousands of pro-democracy demonstrators had been killed there less than six years before. That was in stark contrast with the hundreds of Chinese flying kites and taking photographs.

The next day we went to the Temple of the Reclining Buddha at Fragrant Hills Park, where we did walking meditation on the road leading to the temple and through the grounds. In the main temple, which is now a museum, we took off our shoes and were allowed into the inner sanctum to make prostrations, light incense, and chant the Heart Sutra to pay our respects to all Chinese Buddhist ancestors, while many Chinese tourists gathered round. The temple grounds were beautifully shaded and evoked a feeling of great serenity. As Thay invited the large temple bell, we could imagine the life of practice that once flourished here. Thay explained to us and to the guides the deep meaning of each Chinese expression written on every gate of the temple. Then he looked straight into the eyes of our guides and said, "Your heritage of Buddhist culture is very rich. It would be a great loss if you ignore it." Peter and Hibiscus listened carefully.

Outside the temple gate, Thay sat down under some shade trees and our group of 15 began singing "Breathing In, Breathing Out" in English and Chinese. Our guides asked several questions, and a spontaneous Dharma talk began. Soon more than 50 people had gathered to hear Thay speaking with translation by Jean, about love based on understanding. When he finished, Peter prostrated to him. Later, Peter told Arnie that he experienced a breakthrough in regards to how to treat his own daughter. Our silent, mindful walk through the park was very powerful. Some elderly people joined their palms and bowed. Thay bowed respectfully to a street sweeper. He was deeply moved and joined his palms with tears in his eyes. We could not resist a visit to the Forbidden City, impressive for the sheer volume of ancient buildings and land devoted to the secluded life of the Ming and Qing Dynasties for 500 years.

We did walking meditation for the 90 minutes we were there, stopping to enjoy people from all over this huge country having their pictures taken at every prime location.

Sister Jina and I spent hours early the next morning walking the wonderful, medieval back streets of Beijing. At times we happened upon dirt paths crowded with vendors and sampled some of the cornbread and scallion-flavored white rolls cooked in their makeshift ovens.

We visited Fa Yuan Temple and the Chinese Buddhist Institute. Thay spoke to 60 young monks in golden-brown robes about walking meditation: "I hope you enjoy your time in the Institute and do not just think about the time when you will be the abbot of a big temple. I have been a happy monk for more than 53 years. If we love the Buddha, the way to show our appreciation is to practice his teaching of living deeply your life in every moment," and he briefly taught the gatha, "I Have Arrived, I am home." Thay also spoke of the need for ancient Chinese texts to be translated into modern Chinese for contemporary readers. After hearing Thay speak about arriving in the present moment, the abbot, Yin Hai, obviously refreshed and inspired by the talk, said, "Within 20 minutes, you were able to offer us the cream of the living teachings of the Lord Buddha. Thank you! I hope you all enjoy and arrive in every step during your stay in China."

We went to Kwan Chi Temple and the Chinese Buddhist Association. Master Jing Hui, a chief disciple of the great Chan patriarch Xu Yun, greeted Thay by saying, "The teachers of the past have taught us about the integration of practice in daily life. Thich Nhat Hanh also teaches Chan in everyday life and makes the profound concepts and teachings of the Buddha accessible." Thay urged the renewal of Buddhism in China and the need to drop the language of complicated Buddhist terms that turns young people off, relating how the very intelligent translator for Thay in Moscow did not know how to translate Buddhist terms, and yet many people received the Five Precepts with deep understanding and commitment. Master Jing Hui described their summer camp for university students. He also said, "We want to be in communication with Thay, who has done a good job spreading the Dharma through the West, and we can learn from each other." Thay responded, "We all have the same lineage. If we can explore the teachings of the Buddha, we can help people be happy," adding, "I know conditions are not completely favorable yet, but they are improving."

We traveled by train from Beijing to Shijiazhuang where we stayed in what came to be a very familiar sight—a "four-star" hotel towering above surrounding concrete blocks of apartments and primitive crowded wooden dwellings on winding paths.

Once on a walk, Thay, seeing a child on the street, said, "There are so many children, and yet from time to time I am drawn to a particular child to speak or to bow to him or her. I feel I am recognizing a future monk or nun in a particular child. It is very easy to water seeds here."

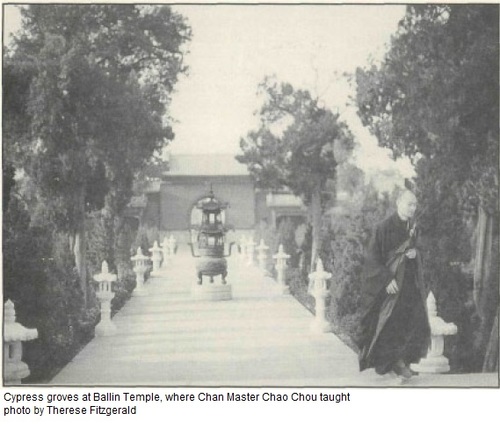

On May 21, we traveled by bus through wheat fields, peach orchards, not far from a coal mining region to visit Bailin Temple, residence during the Tang Dynasty of the great Chan master Chao Chou, famous for this koan: A monk asked Chao Chou, "Why did Bodhidharma come to China?" Chao Chou replied, "Look at the cypress tree in the courtyard." At a Dharma talk to the young resident monks, Thay said, "How can the monk as such a question? He had been practicing here at Bailin Temple for several years and yet he never even noticed the cypress trees in the courtyard. What is the use of asking about Bodhidharma, or ultimate reality? We are very grateful for the cypress trees at this temple. Like young monks and nuns, they are very beautiful and refreshing. When you are surrounded by brothers and sisters practicing deeply, it is easy for you to see the cypress trees. You have time to look deeply and see the trees and other things around you. If you are always lost in regrets about the past and worries about the future, how can you be available to be with the cypress tree?"

Then Thay told the story of the Buddha holding up a flower for those in the assembly to see. Only Mahakasyapa really saw it, and he smiled. "The heart of Buddhist practice is mindfulness, which is the absence of thinking and the presence of being. The Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism, Hui Neng, did not spend much time in the meditation hall, but in the kitchen pounding rice and outside sweeping the yard.

Free from notions, Chao Chou. his successor in later generations, could not avoid seeing the cypress tree deeply. If you understand the teaching of your teacher, you don't have to come to a particular temple. The cypress is alive everywhere, but most people are caught by their ideas of the cypress and cannot see it. So we have to 'kill' the idea of the cypress so the reality of the cypress can reveal itself to us. Master Lin Chi said, 'If you see the Buddha, ou have to kill him.'" It means we must kill our erroneous concepts about the Buddha in order to be able to be in touch with the real Buddha.

"Some time later, another monk came to Bailin Temple wanting to see the cypress tree, which had become famous throughout the country because of this dialogue. Master Chao Chou had already passed away, and his senior disciple told the visitor, 'I don't know anything about a cypress tree!' The visitor was shocked. But the senior disciple of Chao Chou offered him an important teaching. We have to dwell deeply in the present moment, not in our notions." The young monks truly enjoyed Thay's talk about their great ancestor.

It was a sweet pleasure for us to sleep in the temple that night on simple raised platforms with grass mats and to wake early to join the monks for sitting meditation and chanting. After an elaborate breakfast served formally and briskly, we did walking meditation as a Sangha in the inner courtyard with the monks, amidst the noble cypress trees. Thay held the hand of one 13-year-old novice monk and instructed, "Depending on how you walk, it is the Pure Land ovsamsara. If you set aside your worries and preoccupations and walk as a free person, lotuses will bloom under each step." Stopping to practice "tree hugging meditation," Thay said, "Cypress, I am here for you," and, pointing to the young novice, said, "This is a cypress, too."

Getting on the bus to leave Bailin Temple, Thay put his hands on my shoulders and said, "You are a cypress." Later he observed that the young novice was very happy being with TMy. "That will help him when he has difficulties. An important seed was planted. To help one person is great."

Then we visited Chao Chou's famous bridge. The receptivity of the guides, which seemed reflective of the general strong receptivity of the Chinese for Buddhist teachings, demonstrated itself when we visited Chou Chou's bridge. The local guide, echoing Thay, said, "Now we can see not our concept of the bridge, but the actual bridge."

That afternoon we visited Lin Chi Temple, the residence many centuries ago of the great ancestral teacher, Lin Chi (Lam Te in Vietnamese, Rinzai in Japanese). Thay's Zen lineage that came to Vietnam from China is a branch of the Lin Chi sect. The sense of coming home brought tears to our eyes as we offered incense, prostrated to the images of the Buddha and great Master Lin Chi, and then walked among roses in the courtyard and admired the ancient pagoda. Thay looked deeply at the lineage chart carved on the wall. After a delicious lunch, e were about to leave when the abbot, Yu Ming, returned from a trip to Wutaishan, and invited us to join him for a cup of tea and mutual greetings.

The next morning we set out for Wutaishan (Five Terraces Mountain) in Shanxi Province, one of the four major Buddhist holy places in China. There hundreds of temples, monasteries, and nunneries there that have flourished for centuries. It is said to be the domain of Manjusri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. The vast, barren valleys between the five great peaks were breathtaking in their awesome beauty, although the extent of the deforestation was shocking. The sheer number of buildings left—for this area was far enough from Beijing to suffer minimally during the Cultural Revolution—is impressive. But a great sadness hangs over much of the area. The hotel we stayed in, for example, was once a monastery, and that is the fate of many former dwellings of religious life. And the monks in many of the temples seem to be busy with the work and business of tourism.

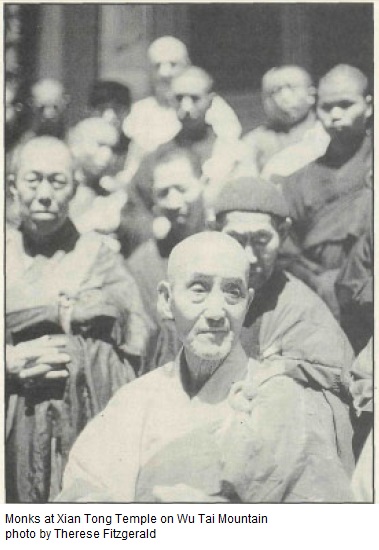

The first monastery we visited, Xian Tong Si, is grand (there are over 400 rooms), although in serious disrepair. We entered the main temple to offer incense, make prostrations, and hear Thay give a Dharma talk. As the 75 monks, all either older than 60 or younger than 25, assembled, I was struck by how tattered their robes were and how unkempt their bodies (like the dusty, artificial flowers on the altar). It was really quite Dickensian—their ruddy, lined faces, their stooped posture, their unshaven faces. When they began chanting in raspy voices amidst much coughing, accompanied by tinny bells and a lifeless drum, I felt a great sadness, and I began to cry deeply. They had obviously struggled so long and been so worn down. Thay addressed the monks, "We have come from far away, and we are very happy to be here with you. We would like to bow to you and the patriarchs." The pain was unmistakable. Thay spoke about coming from a country "where there was great suffering from wars during which teachers and disciples were killed. There was much I had to transform, and thanks to the practice of mindfulness, happiness and peace are possible."

Thay gave instruction in walking meditation, emphasizing walking slowly so as not to lose the serenity of being a monk. "We lose the life of a monk if we rush around like others. I prefer the simple life not to lose the time to breathe and be myself. It takes me three times longer to walk somewhere, but that does not mean that I have not been able to help many people. I have trained three generations of monks and nuns who are happy and who help others be happy. A good monk is a happy monk, and he does not need to be very busy. If we practice deeply each moment, each step, we will learn to live deeply our life." Later, a young monk approached Thay, prostrated to him, and expressed his desire to practice well. Thay told him, "We have to open ourselves, or we will suffer. When you have difficulties as a monk, don't give up."

Next we visited Bi Shen Temple where the abbot, Shou Ye, age 83, had used the blood of his tongue to write out the Avatamsaka Sutra. The Japanese who occupied the area at the time took the sutra to Japan. The abbot wrote out the Lotus Sutra twice by the blood of his finger. We learned about their summer schedule of study of the Avatamsaka Sutra, and their winter schedule of Zen meditation. Thay gave a Dharma talk to 110 monks about dealing directly with the real problems and suffering of the people, and once again urged the monks to use contemporary language in conveying the teachings of the Buddha and helping people live harmoniously as a family. He talked of the many Dharma doors, including Buddhist psychology, saying that there is a need for monks here to train to be Dharma teachers in the West.

We rose early the next morning to climb 1,080 steps in mindfulness (one step, one inhalation and exhalation) to Manjusri Temple. Four young children with their disabled father were begging on the steps. The oldest sister brought forward the others to be "blessed" by Thay, and he put his hand on their heads. All but one stopped begging for a moment. "The great thing is that they forgot about begging. It's important to stop and relate to them, not just ignore them," Thay said. One man with a stub for an arm yelled at the top of his lungs, "as if to say, 'You recite "Amida Buddha" all day, and yet you ignore a real person in need!'" Thay noticed, and it occurred to me that here was the real Manjusri on the steps to Manjusri Temple.The local guides were so inspired by the practice that they made sure they xeroxed their daily reports to the government that evening for the sake of their studies and practice. "I have never done that walk without getting exhausted," they exclaimed. "He must be enlightened!"

In a meeting with the earthy, ruddy abbot, Thay asked, "Does Manjusri reveal himself from time to time these days?" The abbot responded, "It depends on your luck." Thay put his hand on the abbot's shoulder, smiled, and said, "He is our Manjusri." On a more mundane level, Thay cautioned the abbot to resist bringing in a tram. "Donkeys and horses are okay." The abbot said, "We only have control inside monastery gates. Outside the gate is under governmental control, beyond our control."

We returned from our climb up the mountain full of energy. Thay asked Sister Vien Quang to go to a nearby Buddhist Institute for nuns to see if it might be possible for Thay to meet with, or give a Dharma talk, to the nuns there. It turned out the abbess had read about Thay in many Taiwanese newspapers, and she knew that Thay and the Dalai Lama were known as the two most beloved teachers in the West. So she was very happy to invite Thay.

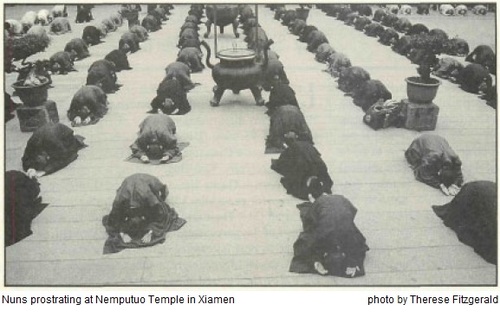

Our visit to this nunnery was the bright spot of our trip to Wutaishan. We felt the loving care of details by the women as soon as we entered the gate. One hundred and sixty nuns, mostly young, greeted us with cheery faces and we walked past dormitories, gardens, and laundry areas beautifully arranged and tended, and a lot of active construction. The nuns and monks from Plum Village were served tea and given blankets to cover their laps during Thay's Dharma talk on the Sutra on the Full Awareness of Breathing and happiness as the fruit of practice. "If the Buddha was a happy person, enjoying life, we students should be happy and smiling." We then had a most enjoyable walking meditation outside. As the sun set, Thay formed a spiral and gathered the nuns close for some discussion about the practice. Then the nuns, beaming with joy, lined up to bid us farewell.

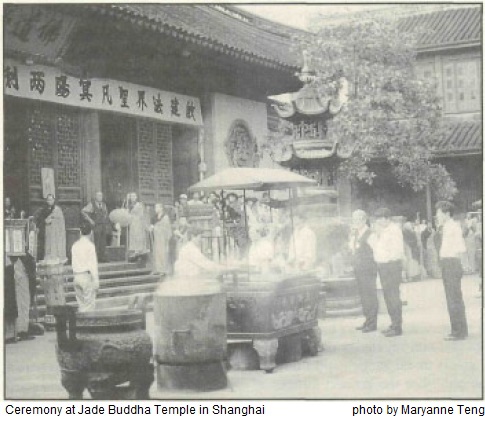

The next day, we went by plane from Taiyuan to Shanghai ("Only 12 million people live here," our guide said) and it was something of a shock after our idyllic days in Wutaishan. But we acclimated quickly and enjoyed the vast variety of architecture and human life. Markets were staggeringly rich with displays of every imaginable vegetable, including eggs caked in mud and mushrooms of every description, and every conceivable animal—snakes galore squirming alive or being skinned of their innards, ducks, pigs cut open and splayed on a table, chickens being decapitated on the spot, and fish and eels.

We met Venerable Ming Yang, a very warm and politic abbot of Long Hua Temple (150 monks, Pure Land practice). At a meeting with him and several elderly laywomen, Thay expressed his understanding that "many young people in the West and intellectuals come to Buddhism, not to worship or ask for favors (of good health and prosperity), but to learn how to transform their suffering. They look at the Five Precepts very deeply. To take refuge without practicing can have no real effect." Ven. Ming Yang described how Buddhism in China is "booming," and he expressed how we were all of the "same family" of Buddhists.