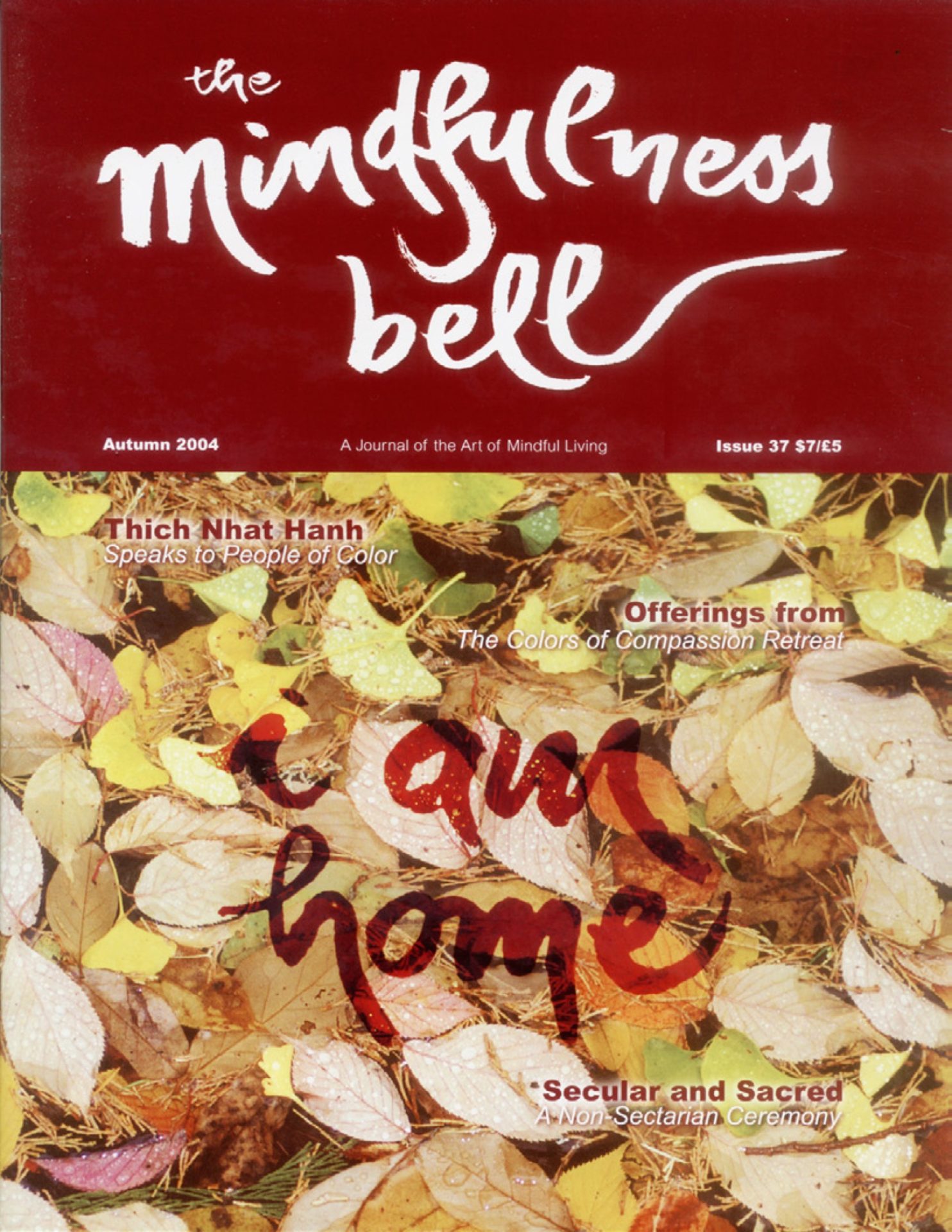

Revelations in a Secular Retreat

by Lynette Monteiro

With the explosion in the use of mindfulness as a psychological intervention, questions are arising about the implications of using a secular mindfulness practice outside a sacred (religious) context. Against this background, the Ottawa Mindfulness Clinic ventured with two Buddhist Sanghas to offer a secular retreat on mindfulness skills to the health care community. What transpired was a rare opportunity to observe the power of concepts and the resilience of practitioners.

Revelations in a Secular Retreat

by Lynette Monteiro

With the explosion in the use of mindfulness as a psychological intervention, questions are arising about the implications of using a secular mindfulness practice outside a sacred (religious) context. Against this background, the Ottawa Mindfulness Clinic ventured with two Buddhist Sanghas to offer a secular retreat on mindfulness skills to the health care community. What transpired was a rare opportunity to observe the power of concepts and the resilience of practitioners.

The theme was “Why meditate? Three perspectives of Mindfulness Meditation.” Dharma teachers Chan Huy and Joseph Emet spoke on mindfulness and the growth of wisdom and creativity. In my role as psychologist, I was asked to explore “Healing Meditation.”

Defining the form of the retreat was a challenge. As a clinical organization, the issue of religious form was the central obstacle. As the planning developed, I found myself becoming obsessed with words: can we say “Buddha,” “Dharma,” “Sangha”? I became focused on the structure: can we have a statue, incense, an altar? Do we bow? Do we prostrate? Do we use the bells?

Slowly, the form of all the retreats I’d ever attended began to dissolve. Daily, I sat with the discomfort of deconstructing the familiar. Mountains were no longer mountains. Rivers ceased to flow in a way I had come to take for granted. The finger pointing to the moon was fully on the grid of my perceptions and I was about to dissect it. Paradoxically, the act of beginning the dismantling was firmly grounded in the faith (the first pillar of Zen) that my practice was resilient in such inquiries. In fact, my personal and professional practice demanded such openness to risk.

What emerged was recognition that my professional discomfort with signs and markers guided me, and protected me from attachment to external objects that can become obstacles to an engaged life. Great Doubt is the second pillar of Zen: the willingness to question every object, every action of body, speech, and mind.

No Dharma Teacher, No Dharma Talk

Designing the talk presented the next obstacle. For almost two decades of academic studies and ten years of professional practice, I have been over-trained in the presentation of data-based scientific papers. Charts, graphs, and Power Point presentations are the rituals of the religion of science. Once more, the sword of understanding sliced through these attachments and what remained was a determination (the third pillar of Zen) to throw myself off a 100-foot pole into the true nature of faith in myself.

The talk explored the skills of stopping, accepting, and taking responsibility. The Serenity Prayer formed the framework, with the story of Angulimala as the central parable of taking personal responsibility to stop. Buddhist mythology flowed easily into psychological theories of awareness, acceptance, and commitment to change. Not being a Dharma teacher, I found myself internally chuckling that I was giving a no-Dharma talk and thus fulfilling my aspiration to no-form.

The outcome was powerful. Participants shared their understanding that we suffer when we cannot accept what we cannot change. To accept the things we cannot change requires stopping; like Angulimala, it is a personal choice to stop one’s suffering. With the clarity of mindfulness, we can see what can be changed. Serenity grows out of allowing our concepts to be dissolved, sitting with the distress of no-form, and opening to the liberation of true emptiness.

Blessing the Sacred in the Secular

The retreat closed with a transmission of the Five Mindfulness Trainings. Though I would have preferred a secular ceremony, we agreed to conduct a Buddhist ceremony and invited the non-Buddhist participants to support those who had chosen to commit to a path of ethical, engaged living. During the ceremony I felt an intense, rising joy seeing my spouse take the vows again in community. He had received his transmission from Thay at a secular retreat in Wisconsin and wanted to express his commitment with his home Sangha as witnesses.

I had intense feelings of discomfort through the ceremony’s religious forms. But when I recognized that we are always vulnerable to our perceptions, sacred and secular became again the mountain and rivers in a blink of the mind’s eye. I may not be ready to merge the secular and religious in a single retreat. However, I have come to value the sacred in the secular as it focuses my attention on the moon, which at this moment shines brightly, fully, and wonderfully through my window.

Lynette Monteiro, True Wonderful Fulfillment, is a founder of the Ottawa Mindfulness Clinic.