By Phyllis Austin

Late one evening recently, I received a phone call from my sister with sad news. Her daughter, who had been raped at gun point by a felon just a year ago, had been beaten badly by her husband. My family was understandably upset and angry. They have seen my niece through much suffering, including a previous marriage also beset by violence and alcohol. They have anguished about the impact on her two young children, who have been battered emotionally and don’t know what a safe,

By Phyllis Austin

Late one evening recently, I received a phone call from my sister with sad news. Her daughter, who had been raped at gun point by a felon just a year ago, had been beaten badly by her husband. My family was understandably upset and angry. They have seen my niece through much suffering, including a previous marriage also beset by violence and alcohol. They have anguished about the impact on her two young children, who have been battered emotionally and don't know what a safe, secure home is.

In the past, I too have responded with much anger at the men who have brutalized my niece and caused such terrible pain to the children. I have also been pointedly angry at my niece for taking her problems to my aging parents, who are unable to bear such woeful burdens anymore. This time, however, I wasn't furious; I did not feel a need to blame anyone or join in the fray. I was just sick at heart. And the repetitive nature of my niece's troubles jolted me into awareness of how seeds of violence had manifested in my blood family.

Looking deeply, I came to understand that my niece is the garden in which my family's seeds of anger have sprouted and blossom. Seeing this way enables me to be part of her suffering, as well as that of her husband. I could see myself as the one beaten and the beater—because we all are, I believe, co-responsible for the haired and violence in our families, in our society. To truly accept myself as a participant, not an observer, of violence is a crucial point in my life. For a long time, it has been politically and spiritually popular to give lip service to such a notion. But I didn't take it on because I didn't feel it in my gut until now.

In the days after my niece's beating, other family members exploded in ways beyond anger. I sat 1,000 miles away, able to do little concretely. I pondered the question of how anger and violence had been passed on from one generation to another. What kind of "seed storehouses" were my ancestors? How did my family get to this point today—this painful place we share with so many families in America?

My maternal grandparents, with whom my parents, sister and I lived, didn't express anger openly. Had they healed it in themselves, or were their seeds of anger suppressed by strong Victorian mores? My parents, I know, smothered their anger. With no role models for anger, I was into my 40s before I learned how strong my own anger was and how to express it in a healthy way. But do I understand my anger well enough? Who is watering the seeds of my anger now, as well as the seeds of happiness, sorrow, fear, joy, and hope?

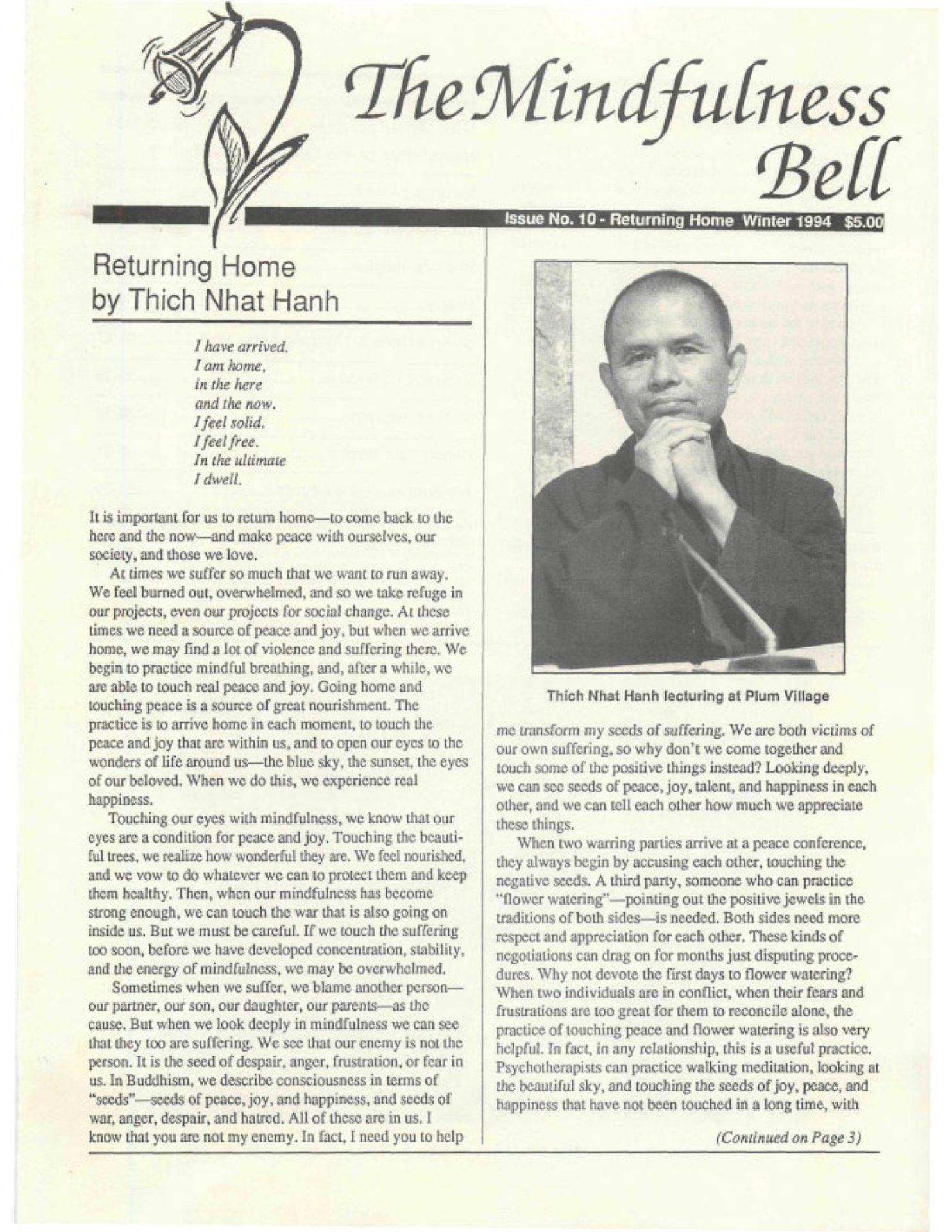

I was fortunate to have just returned from a retreat with Thay when the news of my niece's difficulties arrived. He had focused much of his teachings on transforming anger and violence through mindfulness. From mindfulness, or insight comes love, he says.

"Love is the intention and capacity to bring joy to others and to remove and transform the pain that is in them.. .[when] love is present, relief is there, peace is there." I had read these words before in books Thay has written on the subject. I had listened to them on audio tapes. But being in his presence made me realize I hadn't really grasped them. For the first time, sitting on my cushion a few feet away from him, I "got" the message. So when I returned home and received my sister's call, I was prepared to see the violence not as just my niece's and her husband's. I now saw how I and every member of my family plays a role.

Thay describes the seeds of anger, once watered, rising like a flame into "mind consciousness." Every time anger manifests at the conscious level, "it is strengthened at the base as a seed," he says. "In psychotherapy, it's said we have to be in touch with our anger, experience our anger, allow our anger to be," he notes. "But if we don't know how to do it, it.. .can be very destructive." Thay teaches that when anger arises, "you should invite the seed of mindfulness to manifest because you do have that seed in you too."

This way is nonviolent, non-dualistic, he says. "The energy of mindfulness embraces the energy of anger in the most tender way. In touching your anger with mindfulness, you will bring about a change." The Buddhist tradition considers the seed of mindfulness as the "baby Buddha in us," Thay says. "The baby Buddha is under many layers of forgetfulness and suffering, but it's always there. If you go back and touch the seed of mindfulness, it will grow and begin to generate the kind of energy that has the power to heal and to transform."

With Thay's teachings as a guide, the best way I know to help my family is to nurture the seeds of peace within myself, to be supportive without judgment and blame. Every time I breathe mindfully, I am helping my niece to heal, helping the children to not grow up to be the ones who are beaten, or the ones doing the beating.

Phyllis Austin, a reporter for the Maine Times (where this article originally appeared), lives in Brunswick, Maine.