By Dr. Magda De La Paz Cabrero on

Dharma eyes

“But once our ‘spiritual eyes’ are opened, we’ll never lose the ability to see the wonder of all dharmas, all things.”

Thích Nhất Hạnh1

In my recent pilgrimage to Vietnam to commemorate the second anniversary of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s (Thầy’s) continuation, I do my best to view everything with Dharma eyes.

By Dr. Magda De La Paz Cabrero on

Dharma eyes

“But once our ‘spiritual eyes’ are opened, we’ll never lose the ability to see the wonder of all dharmas, all things.”

Thích Nhất Hạnh1

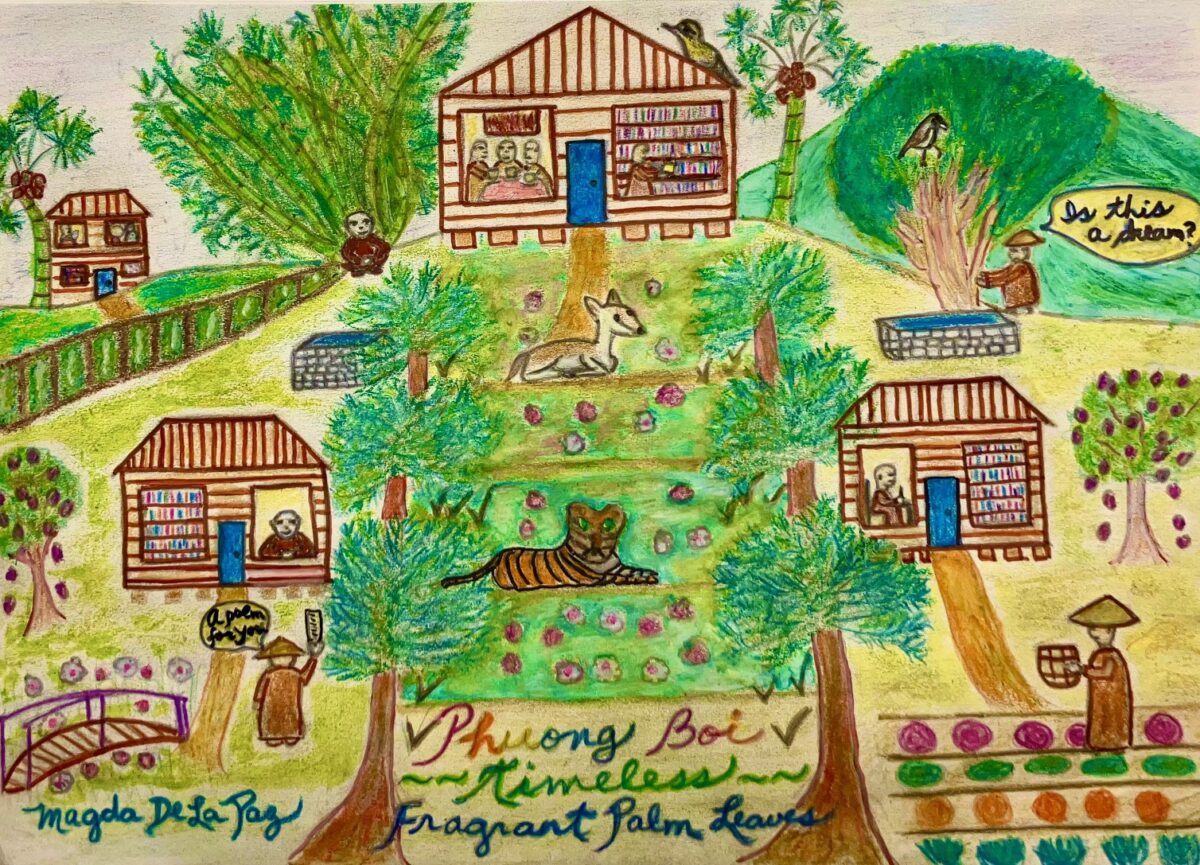

In my recent pilgrimage to Vietnam to commemorate the second anniversary of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s (Thầy’s) continuation, I do my best to view everything with Dharma eyes. My entire experience at Phương Bối, the retreat founded by Thầy at the Dai Lao Mountain in the B’su Danglu forest, feels like an act of mindfulness. At the start of the visit, Sister Tuệ Nghiêm asks us to serve as Thầy’s continuation: “Wherever we sit, Thầy sat at the very spot. Wherever we walk, we are walking in Thầy’s footsteps. Let’s enjoy the place with Thầy’s feet, Thầy’s eyes, Thầy’s ears, and Thầy’s heart.” Having read Thầy’s book Fragrant Palm Leaves, where he describes this hermitage vividly and with melancholy, I try to take in every detail through my physical and spiritual eyes. And feeling extremely privileged, I aspire, through my writing as well as the accompanying illustration, to share Phương Bối with those who would have loved to be here but couldn’t.

Birds of one flock

In Fragrant Palm Leaves Thầy refers to those who lived with him as “birds” who “move[d] back and forth between country villages” and who were eventually forced to fly away. While the pilgrims at Phương Bối come from many places and speak many languages, we are birds of one flock, with Thầy as our leader. Brother Pháp Lưu reads us the farewell poem that Thầy wrote to a man for whom he and his brothers built a hermitage at Phương Bối, called the “Joy of Meditation Hut.” This hermit, Thầy Thanh Từ, eventually became one of the most important Zen masters in Vietnam. “My confidence intact,” the poem reads, “I bid farewell with a peaceful heart.” Upon seeing the hermit become visibly moved by his words, Thầy told him: “I am leaving now, but I’ll come back.” Soon after his departure, the government shut down this hermitage as the monks were suspected of conspiracy. The communist government also denounced Thầy as a property owner, as he had paid ten thousand piasters, the equivalent of $140 USD, to buy this sixty-acre land. Soon after his return from Princeton and Columbia (universities in the US), Thầy returned to Phương Bối where he was arrested on his second visit. After years in exile, Thầy would eventually return to Vietnam and visit Phương Bối once again.

Walking contemplations

“Phương Bối was a reality! She offered us her untamed hills as an enormous soft cradle, blanketed with wildflower and forest grasses. Here, for the first time, we were sheltered from the harshness of worldly affairs.”2

As we do walking meditation, we pass by Thầy’s hut, the stone structure where he collected rainwater, and the eucalyptus tree that he planted nearby. Many of us touch it, remembering how he touched it upon his return in 2005, when he exclaimed: “Is this a dream or reality?” Soon after, we are thrilled to find the first of several two-needle-leaf pine trees whose seeds Thầy brought from Huế, where he grew up and first became a monastic. We then proceed to the top of the hill and come upon the foundation rocks of the Montagnard House. I envision the house’s happy kitchen, and the library that held two thousand books. I imagine Thầy, who could memorize sutras at an incredible speed, devouring these books. We see a new hut where the Joy of Meditation Hut once stood. I picture the nearby Plum Bridge, surrounded by flowers that Thầy loved. I also imagine the two-story meditation space that held yet more books, and on whose walls Thầy’s brother painted the Buddha. We then sit by rows of pine trees to have our lunch, prepared by the family that stayed and sacrificed to protect what remained of Phương Bối.

I think of the freedom Thầy and his brothers felt while they explored the forest, recited poetry, and listened to music. I reflect on the many hours they devoted to discussing and writing about a new “Engaged Buddhism.” I can see the trees with purple sim fruit, the purple trang blossoms, and the white chieu flowers with which they adorned the Buddha’s altar. I can see the tea fields first planted to help Thầy heal when he had no money left for medicine. Was it here that he started to mix tea with ink to create his calligraphy? Was it here that he discovered the healing powers of breathing mindfully? I feel his deep love for the earth, how protected he felt between the earth and the clouds. I think about how here, on a sleepless full moon night, he heard the call of the cosmos: “Imagine someone whose mother has been dead for ten years. Suddenly one day he hears her voice calling to him. That is how I feel when I hear the call of the sky and earth.”3

Timeless space

“But enough, enough. Phương Bối has slipped through our fingers. […] Will Montagnard House remain standing through wind and rain until our return?”4

“The influence of Phương Bối is felt here also, even though Phương Bối is beyond reach in the silent forests of B’su Daglu.”5

As Thầy was checking out a book from a library at Columbia University, he realized that he was the third person to check out the book in almost fifty years. He then had a profound thought: “I was able to encounter two people in space, but not in time.”6 I have a similar realization at Phương Bối. While not with him in time, we are meeting with Thầy in space. I feel a kind of timelessness, a state beyond birth and death, in which past, present, and future fuse. We are all impermanent, yet part of a continuous whole. I am filled at that moment with compassion, love, and a deep understanding of the powers of interbeing and interdependence. Even now, miles away from Vietnam, this Pure Land remains very real in my heart.

I also understand why Thầy, master of the present moment, but also human, wrote: “The more I long for Phương Bối, the sadder I feel.”7 Reading about this yearning for a past that will never return helps the immigrant in me understand and identify with the exile in Thầy.

Seeds in the mud

While here, I reflect on the significance of seeds. The seeds that Thầy planted in this mud would ultimately yield healing tea, a variety of nourishing fruits and vegetables, the eucalyptus, and the pine trees. I start to appreciate that the seeds of what later became “the lotus” of Plum Village were cultivated in the “mud” of Phương Bối: simplicity, harmony, refuge, and healing. Here one is supported and comforted between the earth and sky, surrounded by Dharma brothers and sisters. Here I can truly feel that “I have arrived, I am home,” in a place where people from all paths of life walk with the distinctive slow stroll.

Birds scattering to the wind

As we walk in silence to return to our buses, Thầy’s image of “birds who scattered to the wind” comes to mind. We, the privileged few who have walked, seen, touched, and sat with Thầy’s Dharma body on this sacred land today, will also soon scatter to the wind. But we carry this land inside of our hearts, ready to share it wherever we go.

Poem Thầy wrote for Thầy Thanh Từ

Clouds softly pillow the mountain peak. The breeze is fragrant with tea blossoms. The joy of meditation remains unshakable. The forest offers floral perfumes. One morning we awaken, fog wrapped around the roof. With fresh laughter, we bid farewell. The musical clamor of birds sends us back on the ten thousand paths, to watch a dream as generous as the sea. A flicker of fire from the familiar stove warms the evening shadows as they fall. Impermanent, self-emptied life, filled with impostors whose sweet speech hides a wicked heart. My confidence intact, I bid farewell with a peaceful heart. The affairs of this world are merely a dream. Don’t forget that days and months race by as quickly as a young horse. The stream of birth and death dissolves, but our friendship never disappears.8

1 Thích Nhất Hạnh, Fragrant Palm Leaves, (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2020), p. 102.

2 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 19.

3 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 31.

4 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 59.

5 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 191.

6 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 84.

7 Fragrant Palm Leaves, p. 6.

8 Call Me By My True Names: The Collected Poems of Thích Nhất Hạnh, (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2022), p. 186.