By Shelley Anderson

How do you help people facing grave injustices to develop compassion in action?

This was the challenge facing me and the Buddhist nonviolence trainer Ouyporn Khuankaew, when we were asked to lead advanced nonviolence training for Cambodian activists.

The advanced training was to follow up on a nonviolence training Ouyporn and I had co-facilitated in Phnom Penh in the year 2000. That training had involved a challenging mix of nineteen university students,

By Shelley Anderson

How do you help people facing grave injustices to develop compassion in action?

This was the challenge facing me and the Buddhist nonviolence trainer Ouyporn Khuankaew, when we were asked to lead advanced nonviolence training for Cambodian activists.

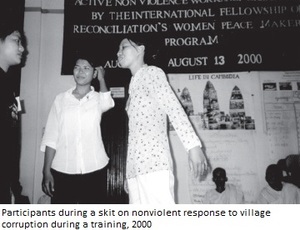

The advanced training was to follow up on a nonviolence training Ouyporn and I had co-facilitated in Phnom Penh in the year 2000. That training had involved a challenging mix of nineteen university students, mostly younger women, and five illiterate older Buddhist nuns. The participants had belonged to two very different social groups that seldom interacted. The advanced training, too, would bring together groups that seldom mixed: university students from the urban center of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, and villagers from some of Cambodia’s poorest provinces.

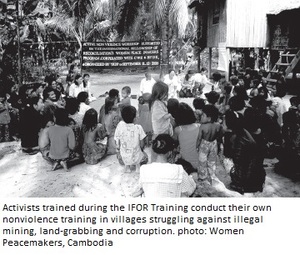

The request to help facilitate the advanced training was exciting for several reasons. Since the first nonviolence training, the university students had been conducting their own trainings. They called themselves the Women Peace Makers group, and first aided girls in factories in the capital who were organizing for better working conditions. They then learned of villagers in rural areas who were struggling non-violently to stop illegal logging or land grabbing, and began to reach out to those communities. The advanced training would be a wonderful opportunity to learn more about these struggles, which seldom receive any attention from the international community.

Even more important, both Ouyporn and I were eager to learn more about engaged Buddhism in Cambodia. We are both Buddhist practitioners and especially influenced by Thich Nhat Hanh’s call to bring Buddhist perspectives to contemporary social problems. The desire to relieve suffering and to further develop the practice of Buddhist active nonviolence motivated us.

Bringing the Temple to the Streets

Cambodia has its own history of engaged Buddhism. Cambodia’s Supreme Patriarch, the monk Maha Ghosananda, has also called upon Buddhist practitioners to “bring the temple into the streets.” Similar to Thay’s work to end the devastating war in Vietnam, in 1987 Maha Ghosananda led a group of Buddhists monks and nuns to the United Nations’ sponsored peace talks in Indonesia. There he told all the fighting factions that he would form a fifth army. But this would be an “army of peace” whose ammunition would be “bullets of loving kindness.” “It will be an army absolutely without guns or partisan politics,” he announced, “an army of reconciliation with so much courage that it turns away from violence, an army dedicated wholly to peace and to the end of suffering.”

Since 1992 thousands of nuns, monks and lay people have joined Maha Ghosananda’s annual peace marches throughout Cambodia, called Dhammayietras. The first Dhammayietra played a very important role in de-escalating the atmosphere of violence during Cambodia’s first election. They have helped spread the values of nonviolence and compassion, and spread life-saving information on landmines, AIDS and the need to stop deforestation.

Many of the participants were surprised during our first training in Cambodia when we talked about Cambodia’s long history of active nonviolence, citing the example of Maha Ghosananda. They expected to hear instead about new, Western ideas on conflict resolution. But nonviolence, sometimes translated in Asia as ahimsa or “non-harming”, is evident in every culture and is as old as humanity. One aim of nonviolence training is to promote awareness of the values and resources that make for a culture of peace and nonviolence in the participants’ own culture.

This was especially important in Cambodia, where the scars of war remain unhealed. Between 1975 and 1979, at least one million Cambodians died of executions, forced labor, malnutrition, and disease. This was the period of the Khmer Rouge, the armed Cambodia force that outlawed money, schools, private property, and law courts. In this country where ninety-five percent of the population is Buddhist, the practice of religion was outlawed. Monks and nuns were forced to disrobe or be killed. An estimated 60,000 Buddhist monks died from starvation or execution during the Khmer Rouge years.

In the 1990’s Buddhist groups, such as the U.S. based Buddhist Peace Fellowship and the Thailand based International Network of Engaged Buddhists, helped to rebuild Buddhism by bringing in teaching materials on the Dharma and by supporting the education of Cambodian monks and nuns. Today, in a Cambodia where both politics and the courts are corrupt, the ordained Sangha is one of the few social institutions ordinary people trust.

Compassion in Action

Buddhism was obviously an important tool that the thirty-nine participants in the advanced training, held in August 2002, could use. We encouraged participants to use the Four Noble Truths in the training session on ways to analyze a conflict. First, identify the conflict, then look at the causes of the conflict. Then realize that solutions to the conflict were possible. This third truth could not be over estimated, because it is the basis of hope. There is mass corruption in Cambodian society. The rich, who may make their money from drugs, prostitution, or the exploitation of Cambodia’s dwindling natural resources, often bribe officials, while the poor can be picked up and thrown into jail at the whim of police. There was brutalization on a mass scale during the Khmer Rouge years. The trauma remains and violence is still common in Cambodia. Maintaining hope in such a situation is no small feat.

The fourth step in conflict analysis based on the Four Noble Truths involves identifying concrete ways to a solution. Tools to help the participants discover ways to find just solutions to social problems were explored. Many skits and practical exercises were held during the six-day training. They were all based on practical problems that the participants faced in their everyday lives. These problems included how to continue a nonviolent struggle after the villagers’ first action had failed; how to encourage people to try nonviolent methods rather than violence; and how to continue a nonviolent struggle even after the leaders have been killed.

The villagers, and the students who supported them, faced possible imprisonment. Corrupt police would be paid to put them in jail, or to beat them up. The deep belief in Buddhism gave some of the participants the courage to continue their struggles in the face of such massive odds. One of the participants was an older man, the leader of a village. In his village people make their living from fishing. But businesses were threatening their livelihood. Illegal trawlers were fishing in the traditional areas, capturing or killing all the fish. After their many complaints to the police were ignored, the villagers confiscated the trawlers, carefully explaining to the trawler crews why they were doing this.

The businessman, who refused to meet with the villagers, filed a court case, claiming they had destroyed his property. He also threatened to kill some of the villagers. This was no idle threat: in some villages there are many widows whose husbands have been killed after protesting illegal fishing.

During the training, the village leader said, “The Buddha teaches us that everything will change. He teaches us that we all will die. So why should I be afraid of being killed? Since I will die, I would rather die for something important, rather than for something unimportant.” The entire room full of participants clapped and cheered this statement.

In addition to tools such as deep listening and conflict analysis, Ouyporn and I encouraged the participants to cultivate meditation. This tool to help cultivate inner peace would support the activists when dealing with the inevitable strong emotions of anger and fear. Every day we would begin by sitting in silence. Many participants had never meditated before. They were awkward at first, shifting uneasily on the bamboo matting which covered the floor.

After each silent sitting, we invited questions. “Why concentrate on the breath?” “Why do my thoughts constantly go back to my boyfriend, who made me very sad?” “My back hurts, am I doing something wrong?” “Why do you ring a bell; the meditation teacher at my temple never does this?” Were some of the questions.

Ouyporn and I shared our experiences with meditation, and repeated why it is important for activists to be still and reflective. Meditation is a tool as useful as conflict analysis models or any other organizing skill, we said. It can help us develop the inner strength to continue the struggle for peace even when everything and everyone around us says to give up.

This inner strength was especially important for the women in the training. Although women are now sixty percent of the population, because so many men and boys were killed by the Khmer Rouge, women have little power or respect in Cambodian society. “Cambodian women should be gentle, modest and shy,” said one woman. “Choosing a husband is the responsibility of the parents, not the daughter herself. A woman’s role is to know how to cook, take care of the children and serve her husband.” The women students (who form a minority in the country, as only fourteen percent of university students are female) talked about family pressure to give up their studies and social change work, in order to marry. Some participants cried when they also told how some villagers assume the women students must be prostitutes, because how else could a woman be free to travel from the city to the countryside?

At the end of the advanced training some participants said that the meditation was one of the most useful tools they learned. Ouyporn and I learned much from all the participants, especially about perseverance and courage. All of us learned a little more about how the rich insights of Buddhism can be applied to the most destructive problems of the modern world.

Shelley Anderson, True Great Harmony, coordinates the Women Peacemakers Program of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation and lives in Holland.