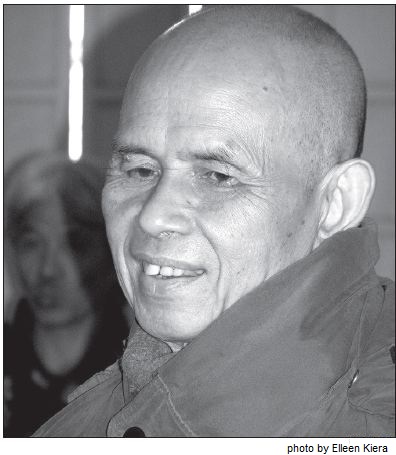

Good morning, dear Sangha, today is the twenty-third of June, 2005 and we are in the Lovingkindness Temple in the New Hamlet.

Happiness is a practice. We should distinguish between happiness and excitement, and even joy. Many people in the West, especially in North America, think of excitement as happiness. They are thinking of something, or expecting something that they consider to be happiness, and, for them, that is already happiness.

Good morning, dear Sangha, today is the twenty-third of June, 2005 and we are in the Lovingkindness Temple in the New Hamlet.

Happiness is a practice. We should distinguish between happiness and excitement, and even joy. Many people in the West, especially in North America, think of excitement as happiness. They are thinking of something, or expecting something that they consider to be happiness, and, for them, that is already happiness. But when you are excited you are not really peaceful. True happiness should be based on peace, and in true happiness there is no longer any excitement.

Suppose you are walking in a desert and you are dying of thirst. Suddenly you see an oasis and you know that once you get there, there will be a stream of water and you can drink so you will survive. Although you have not actually seen or drunk the water you feel something: that is excitement, that is hope, that is joy, but not happiness yet. In Buddhist psychology we distinguish clearly between excitement, joy, and happiness. True happiness must be founded on peace. Therefore, if you don’t have peace in yourself you have not experienced true happiness.

Training Yourself to Be Happy

You have to cultivate happiness; you cannot buy it in the supermarket. It is like playing tennis: you cannot buy the joy of playing tennis in the supermarket. You can buy the ball and the racket, but you cannot buy the joy of playing. In order to experience the joy of tennis you have to learn, to train yourself to play. In the same way, you have to cultivate happiness.

Walking meditation is a wonderful way to train yourself to be happy. You are here, and you look in the distance and see a pine tree. You make the determination that while walking to the pine tree, you will enjoy every step, that every step will provide you with peace and happiness. Peace and happiness that have the power to nourish, to heal, to satisfy.

There are those of us who are capable of going from here to the pine tree in that way, enjoying every step we make. We are not disturbed by anything: not by the past, not by the future; not by projects, not by excitement. Not even by joy, because in joy there is still excitement and not enough peace. And if you are well-trained in walking meditation, with each step you can experience peace, happiness, and fulfillment. You are capable of truly touching the earth with each step. You see that being alive, being established fully in the present moment and taking one step and touching the wonders of life in that step can be a wonder, and you live that wonder every moment of walking. If you have the capacity to walk like that, you are walking in the Kingdom of God or in the Pure Land of the Buddha.

So you may challenge yourself: I will do walking meditation from here to the pine tree. I vow that I will succeed. If you are not free, your steps will not bring you happiness and peace. So cultivating happiness is also cultivating freedom. Freedom from what? Freedom from the things that upset you, that keep you from being peaceful, that prevent you from being fully present in the here and the now.

One nun wrote to Thay that she has a friend visiting Plum Village. Her friend did not take the monastic path; instead she married, and now has a family, a job, a house, a car, and everything she needs for her life. She’s lucky because her husband is a good man; he does not create too many problems. Her job is enjoyable, with a salary above average. Her house is beautiful. She thinks of her relationship as a good one although it is not as she expected; sure, you can never have exactly what you expect.

And yet, she does not feel happy and she is depressed. Intellectually she knows that in terms of comfort, she has everything. Many of us think of happiness in these terms, as having material and emotional comforts. Not many people are as successful as that friend, and she knows that she is fortunate. And yet she is not happy.

We Are Immune to Happiness

We have the tendency to think of happiness as something we will obtain in the future. We expect happiness. We think that now we don’t have the conditions we think we need to be happy, but that once we have them, happiness will be there. For example, you want to have a diploma because you think that without that diploma you cannot be happy. So you think of the diploma day and night and you do everything to get that diploma because you believe that diploma will bring you happiness. And you forecast that happiness will be there tomorrow, when you get the diploma. There may be joy and satisfaction in the days and weeks that follow the moment you receive your diploma, but you adapt to that new condition very quickly, and in just a few weeks you don’t feel happy anymore. You become used to having a diploma. So that kind of excitement, that kind of happiness is very short-lived. We are immune to happiness; we get used to our happiness, and after a while we don’t feel happy any longer.

People have made studies of poor people who have won lotteries and have become millionaires. The studies found that after two or three months the person returns to the emotional state they were in before winning the lottery. From two to three months. And during the three months there is not exactly happiness; there is a lot of thinking, a lot of excitement, a lot of planning and so on—not exactly happiness. But three months later, he falls back to exactly the same emotional level as he was before winning the lottery. So having a lot of money does not mean you will be happy.

Perhaps you want to marry someone, thinking that if you can’t marry him or her, then you cannot be happy. You believe that happiness will be great after you marry that person. After you marry, you may have a time of happiness, but eventually happiness vanishes. There is no longer any excitement, any joy, and of course, no happiness. What you get is not what you expected. Then perhaps you know that what you have attained will not continue for a long time. Even if you have a good job, you are not sure you can keep it for a long time. You may be laid off, so underneath there is fear and uncertainty. This type of happiness, without peace, has the element of fear and cannot be true happiness. The person you are living with may betray you one day; you cannot be sure that person will be faithful to you for a long time. So fear and uncertainty is present also. To preserve these so-called conditions of happiness you have to be busy all day long. And with these worries, uncertainties, and busyness, you don’t feel happy and you become depressed.

So we learn that happiness is not something we get after we obtain the so-called conditions of happiness: namely, the material and emotional comforts. True happiness does not depend on these comforts; nothing can remove it from you. When we come to a practice center, we are looking to learn how to cultivate true happiness.

The Buddha’s Teaching on Happiness

When I was a young monk people told me that the teachings of the Buddha could be summarized in four short sentences. I was not impressed when I read these four sentences. People asked the Buddha how to be happy and he said that all the Buddhas teach the same thing:

Refrain from doing bad thingsTry to do good thingsAnd learn to subdue, purify your mindThat is the teaching of all Buddhas. (1)

Very simple; and because of that, I was not impressed. I said, “Everyone agrees that you have to do good things and refrain from doing bad things. To subdue and purify your mind is too vague.” But after sixty years of practice I have another idea of the teaching. I see now it is very deep, and that it is a real teaching of happiness.

Let us consider together. The gatha I learned is in Chinese, in four lines, and each line contains four words.

The bad things, don’t do it.The good things, try to do it.

It does not seem to be very deep: nothing spectacular about it. Everyone knows, the good things you should do and the bad things you should not do. You don’t need to be a Buddha to give such a teaching. So I was not impressed. The third line and fourth lines are:

Try to purify, subdue your own mindThat is the teaching of all Buddhas.

Now I understand that the bad things you should refrain from are those that create suffering for you and for other people, including other living beings and the environment. But how can you recognize something as good to do, or as bad to do? Mindfulness. Mindfulness helps you to know that this is a good thing to do and this is a bad thing to do; to know that if you do these bad things you bring suffering to you and to the people around you. So the bad things bring suffering to you and others. This is a very simple and yet precise definition of good and bad. And of course, the good things are the things that bring you joy and true happiness. Anything that is good, try to do it. That means anything that can bring peace, stability, and joy to you and to other people. It is easy to say, it is easy to understand, but it is not easy to do or to refrain from doing. The first two things depend entirely on the third thing: to purify, subdue your mind. The mind is the ground of everything.

The Most Special Thing in Buddhism

If there is confusion in your mind, if there is anger and craving in your mind, then your mind is not pure, your mind is not subdued, and even if you want to do good things you cannot do them, and even if you want to refrain from doing bad things you cannot. And that is why the ground, the root, is your mind.

When you refrain from doing bad things you are practicing compassion, because refraining from doing bad things means not bringing suffering to you or to other people. Practicing compassion is practicing happiness, because happiness is the absence of suffering. And then:

Try to do good things: karuna, maitri. This teaching is the practice of love, of compassion, and of lovingkindness. When you understand, the first two sentences have a lot of meaning. You practice love, you practice compassion, you practice lovingkindness and you know that practicing love brings happiness. Happiness cannot be without love. The Buddhas recommend us to love, and the concrete way is to refrain from causing suffering and to offer happiness.

You can do this easily and beautifully only when you know how to subdue your mind, how to purify your mind. This is very special. If you ask the question, “What is the most special thing in Buddhism?” the answer is that it is the art of subduing your mind, of purifying your mind. Because Buddhism gives us the concrete teaching so that we can purify, subdue, and transform our mind. And once our mind is purified, subdued, and transformed, then happiness becomes possible. With a mind that still has a lot of confusion, anger, craving, and misunderstanding, there can be no love and no happiness for oneself and for the world. So the most important thing you should learn is the art of subduing and purifying your mind. If you have not got that, you have not got anything from Buddhism.

T.S. Eliot was a poet, playwright, and critic, born in Boston in 1888. When he grew up he went to Europe and he liked it there so he became a British citizen. His poetry is a kind of meditation; he tries to look deeply and many of his poems are like gathas presenting his understanding. He said that he always tried to look deeply; those are the words he used: to look deeply, to understand the roots of suffering. He found out that the mind is the root of all suffering; our own mind is the foundation of all the suffering we have. That is exactly what the Buddha said. The suffering we have to bear and undergo all comes from within our mind, a mind that is not purified, that is not transformed and subdued. But T.S. Eliot only said half of what the Buddha said. The Buddha said that all suffering comes from the mind, but also that all happiness comes from the mind. All happiness too. So the mind that remains unsubdued, untransformed, confused with hatred and discrimination, brings a lot of unhappiness and suffering; but the purified and subdued mind can bring a lot of happiness to yourself and the people around you.

When you walk from here to the pine tree you begin with one step, and you train yourself in such a way that that step has within it the energy of mindfulness, concentration, and insight. If you really practice walking meditation, you will find out that every step you make can generate the energy of mindfulness, concentration, and insight, bringing you a lot of happiness. Because the three elements–– mindfulness, concentration, and insight–– purify and subdue your mind and bring out all the goodness of your mind. When you walk like this, you are first aware that you are making a step: that is the energy of mindfulness. I am here. I am alive. I am making a step. You step and you know you are making a step. That is mindfulness of walking. The mindfulness helps you to be in the here and the now, fully present, fully alive so that you can make the step. Master Linji said, “The miracle is not to walk on air, or on water, or on fire. The real miracle is to walk on earth.” And walking like that––with mindfulness, concentration, and insight––is performing a miracle. You are truly alive. You are truly present, touching the wonders of life within you and around you. That is a miracle.

Most of us walk like sleepwalkers. We walk, but we are not there. We don’t experience life, or the wonders of life. There is no joy. We are sleepwalking through our own life and our life is a dream. Buddhism is about waking up from your dream. Awakening. One mindful step can be a factor of awakening that brings you to life, that brings you the miracle of being alive. And when mindfulness is there, concentration is there, because mindfulness contains concentration. You can be less or more concentrated. You may be fifty, sixty, or ninety percent concentrated on your step, but the more concentrated the more you have a chance to break through into insight. Mindfulness, concentration, insight: smirti, samadhi, prajna. Every step you make can generate these three powers, these three energies. And if you are a strong practitioner then these three energies are very powerful and every step can bring you a lot of happiness, the happiness of a Buddha.

Mindfulness and concentration bring insight. Insight is a product of the practice. It is like the flower or fruit of the practice. Like an orange tree offers blossoms and oranges. What kind of insight? The insight of impermanence, of no-self, and interbeing.

Happiness Is Impermanent

Impermanence means that everything is changing, including the happiness that you are experiencing. The step you are making allows you to get in touch with the Kingdom of God, with the Pure Land of the Buddha, with all the wonders of life that bring happiness. But that happiness is also impermanent. It lasts only for one step; if the next step does not have mindfulness, concentration, and insight, then happiness will die. However, you know that you are capable of making a second step which also generates the three powers of mindfulness, concentration, and insight, so you have the power to make happiness last longer. Happiness is impermanent; we know the law of impermanence, and that is why we know that we can continue to generate the next moment of happiness. Just as when we ride a bicycle, we continue to pedal so that the movement can continue.

Happiness is impermanent but it can be renewed, and that is insight. You are also impermanent and renewable, like your breath, like your steps. You are not something permanent experiencing something impermanent. You are something impermanent experiencing something impermanent. Although it is impermanent, happiness is possible; the same with you. And if happiness can be renewed, so can you; because you in the next moment is the renewal of you. You are always changing, so you are experiencing impermanence in your happiness and in yourself. It’s wonderful to know that happiness can last only one in-breath or one step, because we know that we can renew it in another step or another breath, provided we know the art of generating mindfulness, concentration, and insight.

The Insight of Interbeing

Happiness is no-self, because the nature of happiness is interbeing. That is why you are not looking for happiness as an individual. You are making happiness with the insight of interbeing. The father knows that if the son is not happy then he cannot be truly happy, so while the father seeks his own happiness, he also seeks happiness for his son. And that is why the first two sentences have a wonderful meaning. Your mindful steps are not for you alone, they are for your partner and friends as well. Because the moment you stop suffering, the other person profits. You are not cultivating your individual happiness. You are walking for him, for her, you are walking for all of us. Because if you have some peace in you, that is not only good for you but good for all of us.

With that mindful step, it might look as though you are practicing as an individual. You are trying to do something for yourself. You are trying to find some peace, some stability, some happiness. It looks egoistic, when you have not touched the nature of no-self. But, with insight, you see that everything good that you are doing for yourself you are doing for all of us. You don’t have a self-complex anymore. And that is the insight of interbeing.

If, in a family of four, only one person practices, that practice will benefit all four, not only the practitioner. When that person practices correctly, she gets the insight of no-self and she knows that she’s doing it for everyone. Just as when she cleans the toilet, she cleans the toilet for everyone, not just herself.

When a feeling of anger or discrimination manifests, the practitioner recognizes that to allow such an energy to continue is not healthy for oneself or for others in the world. The practitioner practices mindfulness of breathing, of walking, in order to recognize the feeling of anger, to embrace the anger, to look deeply into the nature of the anger, and to know that practicing in order to transform your anger is to practice happiness for yourself and other people. If you don’t practice like that, anger will push you to do things or say things that will make you and others suffer. That is not something to do, but something not to do. And when you practice looking deeply into the nature of your anger, you are doing it for yourself and you are doing it for the world and you have the insight of no-self.

With the insight of no-self you no longer seek the kind of happiness that will make other people suffer. The insight of impermanence will help bring the insight of no-self. And no-self means interdependence, interconnectedness, interbeing. This is the kind of insight that can liberate you and can liberate the world. With that kind of practice you subdue your mind, you purify your mind. A mind that is not purified or subdued contains a lot of delusion. And that is why practicing looking deeply to see the nature of impermanence and no-self means to take away the element of ignorance and delusion within yourself. That is to purify yourself. When the element of ignorance is no longer there, the element of anger will be transformed. You get angry at him or her or them because you still have the mind of discrimination. He is your enemy. He makes you suffer. He is to be punished. All these thoughts are no longer there because you have already touched the nature of no-self.

Purify Your Mind

To purify your mind is to transform your way of perceiving things, to remove wrong perceptions. When you are able to remove your wrong perceptions you are also able to remove your anger, your hate, your discrimination, and your craving. Because if you crave something, it means you have not seen the true nature of that thing. If you think of happiness in terms of fame, profit, power, and sex, it is not a correct idea of happiness, because you have seen people who have plenty of these things but suffer so much from depression and want to kill themselves. Understanding that you have wisdom within you frees you from craving. In the teachings of the Buddha, our mind can be intoxicated by many kinds of poison: the first is craving, the second is hate or violence, and the third is delusion. The three poisons. To purify your mind is to neutralize and transform these poisons in you. You neutralize these poisons by the three powers: mindfulness, concentration, and insight.

When your mind is purified, it is so easy to do good things and to refrain from doing bad things. But if your mind is still unpurified––filled with hatred, anger, delusion, and craving––you have a hard time doing good things and refraining from doing bad things. That is why this is the ground of every kind of action that benefits you and benefits the world.

We have invented many types of machines that save a lot of time. We can do wonders with a computer. A computer can work a hundred, a thousand times faster than a typewriter. In farming, it used to take several weeks to plough the fields; now you can do it in a few days. You don’t have to wash your clothes by hand anymore, there’s a washing machine. You don’t have to go fetch the water, the water comes to your kitchen. We have found many ways to save labor, and yet we are much busier than our ancestors were. Everyone is busy; that is a contradiction. Why is that? Because we have acquired so much and we are afraid of losing these things, so we have to work so hard to keep and maintain them. That is why even if you have a lot, you still suffer and become depressed.

Manufacturers of medicine will tell you that the kinds of medicine we consume the most in our society now—tons and tons—are tranquilizers and antidepressants, sedatives. The whole world is under sedation. We need a lot of tranquilizers because we have created a world that has invaded us. We can no longer be peaceful and happy, and that is why we want to forget ourselves. You want to protect yourself from the world, you want to protect yourself from yourself, and that is why you take tranquilizers, antidepressants, sedatives. We are not capable of touching the Kingdom of God, the Pure Land of the Buddha, the wonders of life that have all the powers of healing and nourishing. We have brought into ourselves so many toxins, poisons. The world we have created has come into us. We cannot escape anymore. Not even in our dreams, in our sleep. And the drugs we take are to help us forget the world we have created for a few hours or a few days. When we go in this direction we are no longer civilized, because we are not going in the direction of peace, of solidity, of awakening. The drugs help us not to be awake to reality, because we want to forget reality—the reality of the world, and the reality of the confusion, the craving, and the violence in us.

Peace and happiness are still available, once you are capable of seeing that the conditions we think are essential to our happiness may bring us the opposite of happiness—depression, despair, forgetfulness. And that is why we have to listen to the Buddha. We have to begin with our breath. We have to breathe in mindfully to know that we are alive, that there are still wonders of life around us and in us that we have to touch every minute for our transformation and healing. We have to use our feet to learn how to walk in the Kingdom of God, because each step like that will be transforming, healing, and nourishing. It is still possible.

So from here to the pine tree, I wish you good luck. Make a step in such a way that mindfulness, concentration, and insight can be generated, so that you are capable of being in touch with the here and the now, of touching the wonders of life. Forget about the conditions of happiness that you have been running after for a long time, because you know that once you get them, you will still be unhappy, and then you will have to use the drugs that other people are using. Buddhism is about awakening. We should be awakened to the fact that the situation of the world is like that, and we don’t want to go in that direction. We want true life, true happiness.

Translated from Vietnamese by Chan Phap Tue; edited by Barbara Casey.

(1) This translation is from the Chinese version of the Dhammapada.

To request permission to reprint this article, either online or in print, contact the Mindfulness Bell at editor@mindfulnessbell.org.