Commentary on the Teaching of Master Linji

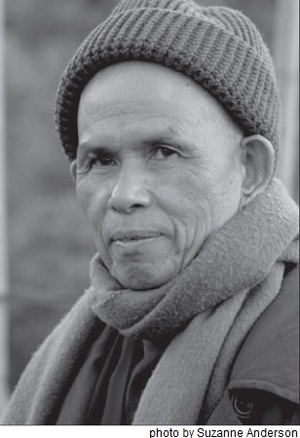

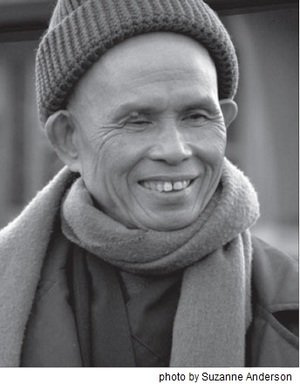

In the fall and winter of 2003–2004, Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay) taught from the Records of Master Linji, a Buddhist monk from ninth-century China. Our lineage descends from Master Linji, so we can consider ourselves his spiritual grandchildren. He is well-known for his use of the stick to wake up students who were ripe enough for such liberation.

Commentary on the Teaching of Master Linji

In the fall and winter of 2003–2004, Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay) taught from the Records of Master Linji, a Buddhist monk from ninth-century China. Our lineage descends from Master Linji, so we can consider ourselves his spiritual grandchildren. He is well-known for his use of the stick to wake up students who were ripe enough for such liberation. The stick was used to skillfully remove the notions and ideas the person was carrying with him or her, or anything else that was an obstacle to living a simple, free life.

The teachings are often given in the form of interactions between Master Linji and those who came to learn from him. The moment of human relationship is thus the moment of waking up, of realizing our blindness and also our capacity to live with freedom and joy. In these interactions there is a fierceness, the punch, and also a tenderness, the willingness to engage, to commit oneself to another for the sake of liberation, for the sake of becoming a real human being.

The original language of Master Linji’s teachings can be confusing, but Thay explains their essence in a way that makes them accessible and meaningful. Thay shows us how to bring them down to earth with the concrete practices of mindful breathing and walking.

The ideal person, our ancestral teacher Linji tell us, is a free person, who lives a simple, authentic life. This person is free from pretention, free from busyness or business—a businessless person. His teachings were medicine for people of his times and they are medicine for us too. Like good medicine, these teachings kill the disease, yet leave the person whole.

Good morning, dear Sangha, today is October the 12th in the year 2003 and we are in the Loving Kindness Temple of the New Hamlet during our autumn retreat.

There is a sutra that was translated into Chinese around the second century. It is called the Sutra of the Forty-Two Chapters. Each chapter is very short and as a novice I had the opportunity to learn the sutra during my first year of studying classical Chinese. In that sutra there is one sentence that says: “My practice is the practice of non-practice.” It reads like this: “My practice is to practice the action of non-action, to practice the practice of no practice and to attain the attainment of no attainment.” When we hear the teachings of our patriarch Linji we hear the same thing. We should be an ordinary person, we should not try to be a saint. If you are seeking for holiness you lose it. Holiness is right there before you but when you begin to seek it you lose it. You begin to run and run and run and you can never catch it. What we learn from the patriarch Linji is not a set of ideas. That is what he hates the most—a set of ideas, especially abstract ideas about the absolute that symbolize the ultimate, the perfection that you are running after. This is what he is always trying to tell us. His teaching is that we should live a simple life properly and become a person without business.

What is your business? You may describe your business as trying to transform yourself, trying to reach enlightenment, trying to save human beings. Throw it away. Don’t consider it to be your business. If you run after that kind of business you cannot be yourself. You are a wonder of life and you are surrounded by wonders of life. A person without enterprise, without any project, without any business—that reflects the practice of non-attainment. There is nothing to obtain.

Our practice is to take refuge in the present moment because the present moment is always available. The present moment is full of life, full of wonders. We don’t have to run towards the future to get it. You are already a wonder and surrounding you are wonders you can experience, if you know how to stop and to become fully present.

Taking Refuge in Your In-Breath

How can you come fully into the present moment? One way is to take refuge in your in-breath. Is this possible? Some may say that our in-breath has a very short life span, perhaps only lasting ten seconds. Why should you take refuge in such a temporary thing? I remember when we held a retreat in Moscow for the first time. Some Protestant teachers from Korea were there, and said, “You should not take refuge in the Buddha because he was a mortal. You should take refuge in Jesus because he is immortal.” Taking refuge in our in-breath is very short and ephemeral. When we talk about taking refuge we think we want something that is very solid and long-lasting so that we can have peace and safety for a long time. If we are to choose between something that is short-lived and something that is long-lived for our place of refuge we may choose the long-lived refuge. Yet the question is, who are you to take refuge? As Master Linji said, you are looking for the Buddha—but who are you who is looking for the Buddha? Are you something that lasts very long? Or do you only last for a second?

We have the tendency to think that we are something that lasts longer than our in-breath, but that is not true. We are just like our in-breath. In the Sutra of the Forty-Two Chapters there is a chapter in which the Buddha asked his disciples how long a human life lasts. One person said, one hundred years; one said, fifty years; one said, one day and one night. Then one person said, it lasts for the length of your in-breath. And the Buddha said to that person, Yes, you have seen the reality of the human life—it lasts for only one in-breath. And it may even be shorter than that because as you breathe in you become another person. The you who is there before the in-breath is no longer the same you after the in-breath. You think that you are something that lasts for a long time so you try to take refuge in something that always remains the same and lasts forever. But if you know that the one who takes refuge and that which we take refuge in are one, you can understand why we can speak of taking refuge in one in-breath. This is very concrete. As we breathe in we can be with our in-breath and we become alive. If we know how to take refuge in our in-breath we can take refuge in our out-breath also.

We feel that we don’t have solidity, stability. We are not ourselves. We are pulled away by so many things, so many ideas, so many projects, so much fear, and so many afflictions. We don’t have peace. That is why we need to take refuge. To take refuge is to be yourself again. It is possible. Taking refuge in your in-breath, you suddenly become yourself right away. You are safe, you are solid. You are fully present right here and now. You are aware that you are a wonder of life and you can get in touch with many wonders of life surrounding you. Oh wonderful in-breath—it makes me feel at home. It makes me feel that I have arrived. It helps me not to run. That is why taking refuge in your in-breath is a very wonderful practice. We breathe in and out anyway, so we don’t have to invent the in-breath before taking refuge in it. It is already there. Bring your mind back to the present moment and enjoy. You suddenly become alive. You suddenly become yourself and you cultivate your solidity and your freedom. You are no longer a victim. You have your sovereignty. Mindful breathing is very important, and it is a non-practice because you breathe in and out anyway. You are sitting there enjoying your in-breath. You don’t seem like you are a practitioner, but you are a true practitioner. You are not trying hard, you are just enjoying your in-breath. That is what our ancestral teacher Linji wants us to do. Not to do anything, just be yourself. Sitting there enjoying your in-breath you become everything, you become immortal.

Taking Refuge in Your Steps

You are always walking, going from your room to the restroom, to the office, to the kitchen. So why don’t you enjoy walking? Why don’t you go home to the present moment and enjoy taking refuge in your steps? Why do you allow yourself to be pulled in many directions? When you are distracted, you are not yourself, you are a victim. But you can change this by taking refuge in your steps right now, right here. It is wonderful to combine your in-breath with one, two, or three steps. In that moment you are truly yourself. You have your sovereignty; you are no longer a victim. You are no longer pulled away by the waves of birth and death. You are no longer drowning in the ocean of afflictions.

People like to say, take refuge in the Buddha, take refuge in the Dharma, take refuge in the Sangha. But, I like to say, take refuge in your in-breath, take refuge in your out-breath, take refuge in your steps. The Buddha may be an abstract idea, but your in-breath is a reality, your steps are a reality. You are looking for the Buddha, you are looking for the Dharma. You are not truly taking refuge in them because you have not found them. But you don’t have to look for your in-breath; it is right there in front of your nose. You don’t have to look for your steps; they are right there in your feet. That is why taking refuge in your in-breath, taking refuge in your steps is very concrete. When you are doing that the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha become concrete also. You don’t have to run after the Buddha; the Buddha will run to you. You don’t have to look for the Dharma; the Dharma will come to you. That is what Master Linji tried to say: You do not need to look for the ultimate —the ultimate will come to you.

Although you do not look like a practitioner, you are a true practitioner because you are practicing the practice of non-practice. You practice in such a way that life becomes a reality in every moment of your day. We are looking for a spiritual path because we don’t have peace, solidity, and freedom. That is what a spiritual path is supposed to bring us. But in the market of spirituality you may be fooled by so many people, so many paths, and so many teachers because what they offer you is just ideas—ideas about the Dharma, about God, about the Sangha. There are so many people selling spirituality because there are so many spiritual seekers. Our ancestral teacher Linji was aware of this. He told us not to be fooled by these teachers, even if they are monks and nuns. Do not believe them because they are not really monks and nuns if they have not truly renounced the worldly life, if they are still looking for such things as fame, profit, and power.

Linji’s Teacher

The teacher of Linji was Master Huang-Bo. When Master Linji was a young monk and had been in the temple for some time he was very eager to learn something directly from his teacher. An elder brother said, “Why don’t you ask the master to teach you something?” Master Linji said, “What should I ask?” His elder brother said, “You can ask: What is the essential idea of Buddhism?” So the young monk Linji went to his teacher and asked: “Dear teacher, what is the main idea of Buddhism?” And his teacher punched him. He asked again: “But teacher, please tell me what is the main idea of Buddhism?” And he got a second punch. But he still persisted and asked a third time: “Dear teacher, it is okay to hit me, but please tell me what is the main idea of Buddhism?” And he got a third punch. He was very disappointed. After some time he left the temple because he thought that his teacher was not very kind to him. After leaving his temple, while on a pilgrimage, he met another teacher called Da-Yu. He asked the young Linji, “Where have you come from?” Linji said, “I come from Master Huang-Bo.” “Why have you left him?” “Because three times I asked him what is the main idea of Buddhism and three times he hit me so I had to leave.” Da-Yu said, “You are a fool. You do not see that he has been extremely compassionate to you. Go home and bow to him.”

The young Linji went home and bowed to his teacher. His teacher said, “Where have you come from?” The young Linji said, “I met a teacher named Da-Yu and I told him that I asked you the question three times and you gave me three blows. He looked at me and he said, ‘You are foolish, you don’t see that your teacher is compassionate.’” And Master Huang-Bo asked, “What did you do after he said that?” In fact, when the teacher Da-Yu told him that he had not seen the compassion of his teacher the young Linji woke up and he said, “Oh, I see, there is not much in the teaching of my teacher.” He realized that these three hits were the real teaching of Buddhism and he laughed and laughed. The teacher Da-Yu shouted at him, “You just told me that your teacher was not kind to you and now you say that there is not much in his teaching. What do you want!”

Do you know how the young Linji reacted? He gave Da-Yu a punch. Da-Yu said, “Well, anyway you are his disciple, not mine. I don’t want to have any more to do with you.” And he left. So when the young Linji went back to his teacher Huang-Bo he told the whole story. Master Huang-Bo said, “If that guy comes here I will give him a punch.” And Linji said, “Don’t wait, here it is.” and Linji punched his teacher. Then Master Huang-Bo called his attendant and said, “Take this fool out of here!” That is the story of our patriarch Linji and his teacher. Do you want to try? Do you dare?

Removing the Object

Linji told us that sometimes you have to remove the object and not the subject. If you come to Thay with your question, with your object then you may get a blow from him. Thay’s style is different, but it is very much in the same spirit. Very often Thay practices removing the object so that the questioner will find him or herself alone without his object. In the teachings of Master Linji there is a passage saying, “In the last twelve years I have not seen anyone coming without an object. Everyone has come to me with an object. As they begin to show it by way of their eyes, I hit their eyes. If they try to show it with their mouth, I hit their mouth. If they want to show it with their hands, I hit their hands.” That is removing the object without removing the subject. If someone comes to you with a question and you spend a lot of time explaining this and that and you are drawn to him, you are not practicing the way of Linji. You have to remove that object of his right away. It may be a very false problem. You have observed Thay doing that with many people. When someone asks a question Thay always tries to remove the question, to give it back to him or to her.

In the market of spirituality you are always looking for something and there are many people who are trying to fool you, presenting you with this or that idea. But Linji is not one of them; he denounced them all. Linji said you should not look outside; you should look inside because God is in you, Buddha is in you, the Dharma is in you. If you have enough faith in that understanding, you have a chance. But if you only look outside you cannot get anywhere. This is the true teaching of Linji. They are selling things because you need them. But if you don’t need them anymore they will not sell them. And that is a chance for them because they spend all their time selling things. If they stop selling they may go home to themselves and get enlightenment, transformation, and healing. If you allow them to continue to sell things like that they will never have a chance. That is why it is very important to stop buying.

You have not come to Plum Village to buy things or ideas, but to have a chance to go home to yourself and to realize that what you have been looking for is already within you. If you want to show your kindness to Thay and the Sangha, take refuge in your in-breath and become fully yourself. Take refuge in your steps and right in that very moment you will have solidity and freedom, you will have the capacity of getting in touch with the wonders of life.

Where do you look for the Kingdom of God? Where do you look for the Pure Land of the Buddha? Where do you look for salvation, for enlightenment? It is in your in-breath and your steps that you can find these things. Don’t do anything, just be an ordinary person. Live your life in an authentic way. Don’t try to use the cosmetics that are provided in the market of spirituality.

Have Faith in Yourself

In the Records of Master Linji the term that our ancestral teacher used for “teacher” is “a good friend” or a “friend who knows about goodness.” We should look upon our teacher as a friend who knows goodness through his or her own experience. That friend should embody stability, solidity, compassion, and understanding. Because he is your friend and has had his own experience of goodness, he can help you. Help you to do what? He can help you to do the same as he has done—to go home to yourself and to get in touch with the seed of goodness that is in you, the seed of solidity and freedom that is in you, the seed of the Kingdom of God that is within you. Don’t have the notion that you have nothing within yourself and that you have to depend only on your teacher. Your teacher is only a friend who can support you to go home to yourself. That is what our ancestral teacher called faith.

In the Records of Master Linji it says, “The practitioners of our time do not succeed because they do not have faith in themselves. They are always looking outside.” They think that they can get compassion and wisdom from the Buddha, from the Dharma, from the Sangha outside of themselves. They don’t know that they are the Buddha, they are the Dharma, and they are the Sangha. They should allow themselves to become the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. They should allow the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha to become themselves. This is the teaching of Master Linji.

Thay can tell you that there is not much in the teachings of Master Linji. We know that the first expression of enlightenment by our ancestral teacher Linji was, “Oh I see, there is not much in the teaching of my teacher.” If you can tell that to Thay, you are a good student. Thay only teaches breathing in and breathing out.

To request permission to reprint this article, either online or in print, contact the Mindfulness Bell at editor@mindfulnessbell.org.