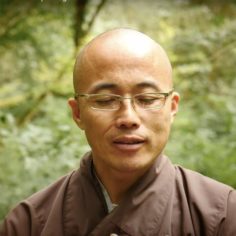

Brother Pháp Dung shares about the relationship between grief and gratitude after Thầy’s passing and his father’s last breath.

By Brother Pháp Dung on

Crying for Thầy

I’ve been reading some of the messages of gratitude friends have written for Thầy on the Plum Village website.

Brother Pháp Dung shares about the relationship between grief and gratitude after Thầy’s passing and his father’s last breath.

By Brother Pháp Dung on

Crying for Thầy

I've been reading some of the messages of gratitude friends have written for Thầy on the Plum Village website. The depth of gratitude Thầy's students express is so moving—some have been to just one retreat, or read one book, or they've never even met Thầy and had the chance to sit next to him. For what are they expressing this profound gratitude? We’re talking about Thầy's energy: the magic, the sacred, the legendary energy of Thầy. And when we express our gratitude and our grief, our task as mindfulness practitioners is not to fuel that natural feeling that we're losing something. When I touch the earth, it's very easy to cry, but with only a tinge of sadness. Mostly, when I cry, I feel Thầy's love. I don’t feel the sadness of “Oh, Thầy's no longer with us.” It's a different kind of crying, crying that motivates me to continue Thầy. My tears may look as though I feel, “Oh, I'm sad and missing Thầy” or “I want to have Thầy forever.” But I am not exactly mourning. My tears are actually very empowering. We all need to know how to cry like that, with healing tears.

This is what Thầy taught me. He prepared us, monks and nuns, all his students and lay friends all over the world. To cry. We know how to cry now. How many of us cry when we go on retreat? Yes, we know how to cry. It's so wonderful to cry.

In our world, there isn't enough crying. People are so afraid of crying. We need a retreat where we teach people how to cry. We can learn a way to cry that is not grasping, not regretful, and not guilty. This crying is very healing and liberating. It allows us to access Thầy's love. His love motivates us, energizes us to continue his work, which is not just about service activism. Thầy's love encourages us to care for and love ourselves. Practicing self-care and self-love is one way we continue Thầy.

Continuing Thầy through transformation

When Deer Park Monastery was first established, I said to our teacher, “Thầy, the West Coast of America is very lucky to have a center like this.” More and more I see how true this is. I witness people coming up here and finding what they need. Outside the dining hall, there's a hill that looks over the valley. Chairs sit under the pepper tree there. I've seen many people just sit there in a chair, looking out into the valley, and I look at their faces change. I like to sit behind one of the bushes and watch them. This is my nourishment. We monks and nuns, we get nourished by people transforming—it’s as if I’m eating your transformation, your liberation, your happiness. It’s nourishing to see someone transform. Isn't it amazing? You have to find good food. You sit there and see someone’s face as they’re contemplating the valley, and you see their face become very still. Their food is getting cold, they’re supposed to eat lunch, but the whole time they’re not eating. Something beautiful is happening. I've seen it over and over in many, many places on this land. People come, they touch the practice, and they know what to do. And you can see their faces change. This is a beautiful thing. Thầy taught us the practice to take care of ourselves, take care of our emotions. An emotion is just an emotion. So, this is how we can continue Thầy's legacy: with our practice.

A place for suffering

In our culture, there's no place for sadness. No place for suffering. But Deer Park is a good place for us to embrace and transform our suffering. If you want to suffer, this is a good place to come; it is the best place to suffer. Thầy has taught us there is a way to suffer. We have the right to suffer, to grieve, to be sad but we also must remember we have a right to practice. Thầy put it more strongly. He said, “You do not have the right to not practice.” But I'll be gentle: we have the right to suffer. It is our human right. It should be written in the UN Declaration of Human Rights; they should add that we have the right to suffer when we know how to take care of our suffering. We all need to learn how to suffer. That is the deepest teaching that I got from Thầy because, as a young man, I ran away from my suffering a lot.

Let's remember we also are practitioners now. So, please do not be attached to your suffering, but practice to be liberated and allow the love of our teacher, the love of our loved ones, to flow through us.

Thầy's body as a teaching

Sometimes we need to be sad, but we can practice to learn how to be sad. And that's beautiful and amazing to me. When we practice, we don't get overwhelmed by sadness, you see. It’s the same with anger, or jealousy, or judgment. These are all just emotions, not things that last. Thầy would encourage us to do our best wherever we are, to come together and find a community, find Dharma friends. Sometimes we are so tired we don't even want to practice. And that's why we need a community.

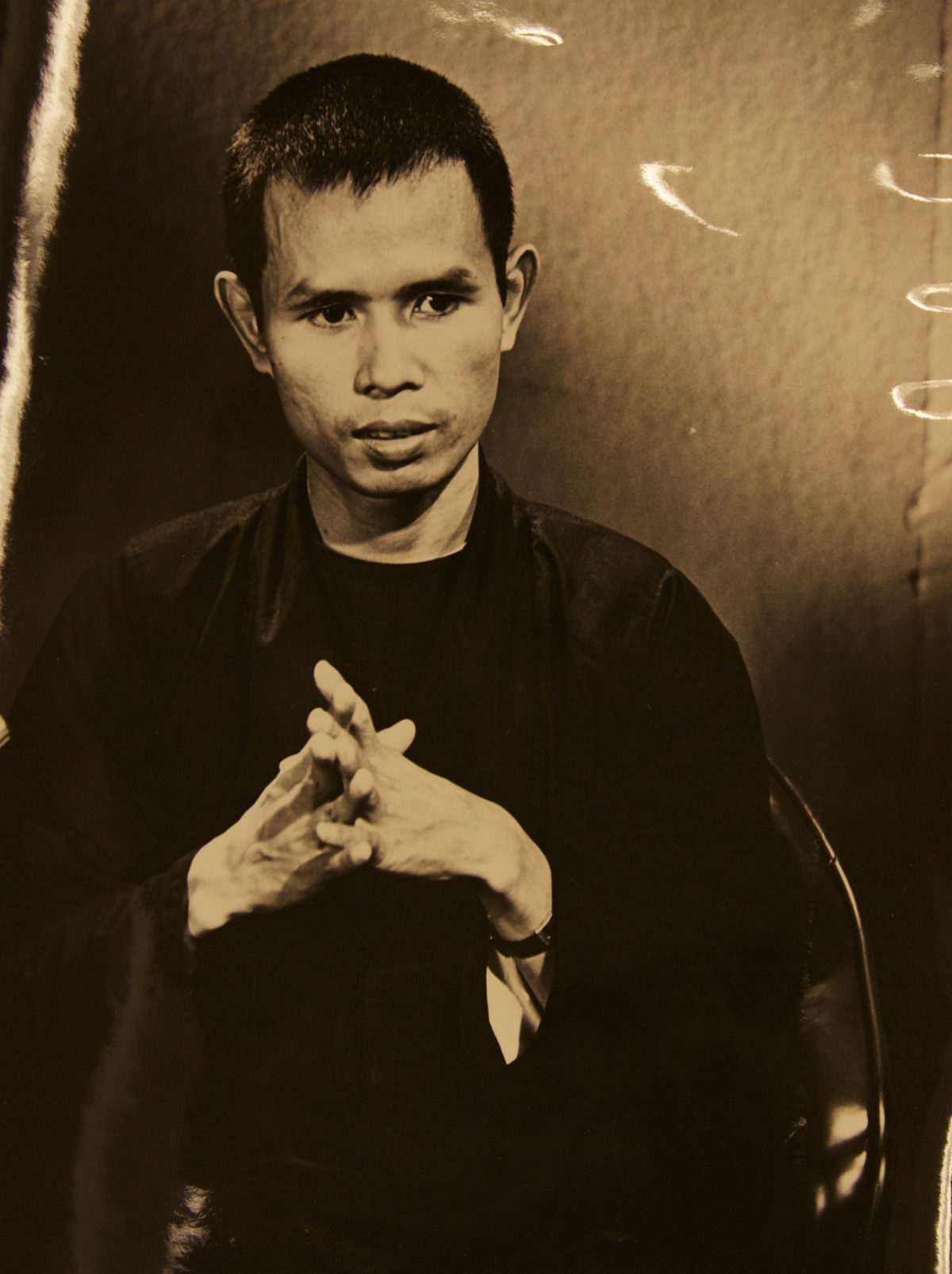

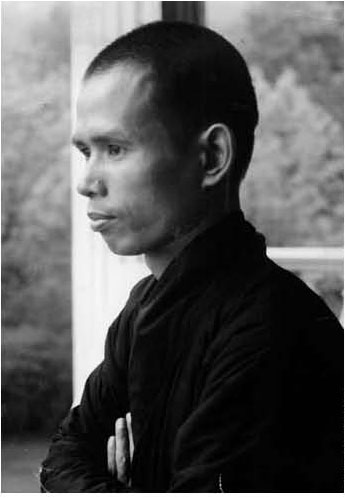

These last few years that Thầy's been sick, I have been very grateful to our teacher and how he showed us the way to practice even with sickness and old age. We know he became a monk when he was sixteen. We know about his practice with Engaged Buddhism during the war in Vietnam. And now, his last teachings, his practice with sickness, old age, and transitioning is so beautiful. The images of his practice are online for the whole world to see. I was watching the funeral ceremonies and feeling so grateful. I received them as a teaching. So this is also a way of practicing during this time: to experience what Thầy's body is going through as a teaching. In the old way of looking, we may think as human beings that we lose somebody when they die. We think they're no longer with us. With the help of the practice, we can recognize the transference, the continuation of Thầy in that process.

In the last six years or so, Thầy has been physically with us, but he hasn't been able to go out physically, teaching and touring. So the monks and nuns have had to do that part to continue his teaching. In a way, Thầy’s physical limitations were training us to go out and teach. What is left for Thầy to do?

The place my father was cremated looks like a warehouse. It is a functional, hygiene-oriented facility. It's a business with offices and desks—very cold. Luckily, when I was there in December of 2021 with all my brothers and sisters, we were able, with the embrace of the Sangha, to hold the space and make it a sacred moment for all the living who were there. We let them witness it was okay to cry, to fear.

Remember impermanence: how to look at it and to use this process. Mourn. Be sad. Do what you need to do and allow that energy to flow.

We will live more fully when we remember this aspect of life. Awareness of impermanence can really infuse you with energy, make you tingle with life like I'm tingling now. But we don't get exposed to impermanence. So when death happens, it’s like an earthquake or a volcano. Our teacher taught me to constantly reflect on this.

As we practice with awareness of Thay’s transition, please use your breathing. Remember to take care of the fear that may arise. It’s a very primal fear of death that comes up when we see a dead body, but impermanence is also very beautiful. It’s a sacred part of being human that we need to honor and look deeply at it. People say, “Why are you guys putting this stuff online?” I was like, “Are you kidding me? You want to hide this aspect?” Of course, those people may not have community to support them and may not have the background to understand. Perhaps the ceremonies triggered an early pain in them. There may be, though, forgetfulness of impermanence. We want to be aware of that risk and protect ourselves with our mindfulness.

Knowing how to practice during these times is very empowering. You understand that every day is a miracle; how you drive on the freeway and get home safely is a miracle. But we're forgetful: it's just the 405 [freeway], I'm in traffic, I'm safe. I'm three hours late, but I'm safe. We forget how dangerous freeway driving is.

Remember impermanence: how to look at it and to use this process. Mourn. Be sad. Do what you need to do and allow that energy to flow. Each one of us will process it differently. This is the power of the practice of mindful breathing. The secret, for me at least, is in the out-breath, because our breathing out is the letting go. One day, it will be your last breath.

My dad simply breathed out and didn't take in another breath. Very peaceful. The nurse came in and asked, “Why is his breathing so light?” and we said, “Oh, he's gone.” She was alarmed. She pressed the button and people came to climb on him. I said, “No, no, get off, get off. He's fine.” And I had to prove to them that we didn’t want him to be resuscitated. There's so much fear and so much wanting him to come back, and the option to try to bring him back, to be hooked up to machines with tubes and so on. “No, no, no, he's fine,” I said. The doctor looked at me and said, “Who are you?” “I'm his son.” And then I showed them proof and they disappeared. It was incredible to experience the intensity, the trauma, the fear and the wanting to grasp at the very last drop of life, but, no, no, no, my dad went peacefully.

So, please practice. Come back to your breath, especially the out-breath when strong emotions come up. Don't try to control it, OK? That's the wrong way to process it. Your body may tremble and shake. When you shake, it’s good. Don't try to not shake. I'm sharing this with you because my body has been shaking a lot lately. That’s your consciousness, your energy. That’s how you received Thầy's love. You see Thầy's love not through a picture. You don’t have to go to Huế to get it. It's available right now. This is the power of the Dharma. You don't get caught by having to do this or that, thinking you have to be close to Thầy, you have to fly to Huế. Thầy has taught us to not be caught by signs, to transcend signs through our practice and conscious breathing.

Please find your favorite practice, something you love to do that you learned after you met Thầy. And if you don't have a favorite practice, find one Thầy liked. He loved drinking tea. You can replace it with coffee if you like. Thầy loved to do walking meditation. He loved eating meditation. He loved being with the community. He loved nature. He loved plants. He loved poetry. He loved music. He loved sitting on a hammock. I do that. I go on a hammock now and let Thầy flow in the hammock with me. He liked to climb the mountains here in Deer Park. Thầy loved his life. He loved his community. And he loved being with the Sangha. Everywhere practitioners gathered, Thầy would go. Even when he was sick, he wanted to come out. Once I was giving a Dharma talk at Upper Hamlet, and Thầy came in. Thầy wanted to be inside the meditation hall, and we sang songs to Thầy. You know, even in the last drop of his life, he was still radiating love to us.

This very special person showed us how to live.

Remember that crying and smiling can happen at the same time. I've been doing that a lot. You cry, but you smile. It's amazing. It's the same thing with feeling suffering or sadness. You feel sad, and then you feel grateful and you feel in touch with Thầy’s love. So you're sad and so grateful. No mud, no lotus. We are so lucky we had our teacher to teach us how to be human and how to suffer, but also how to touch the wonder of the sacred.

A man in the oak grove was sitting alone next to a rock, where he had once sat near Thầy. He found healing there, I bet, because he knew how to breathe. That is nothing less than sacred. I don't know which rock it is, but I know the rock I like to sit next to in the oak grove, and it works for me. So, I encourage you to find a sacred place at home and do the same, to breathe and find healing. We talk a lot about the value of creating an altar in our home that's a place of sacredness, magic, wonder, and spiritual family connection. To young people, I say your altar is kind of like a spiritual bank, and you invest in it every time you touch the earth or light incense. You are connecting with your ancestors, connecting to Thầy. Some of you have a breathing room in your home; that's the kind of place we lack in our society. Offering sacred space is also the role of monasteries and temples—not only the religious aspect, but also the practice part. So, make a place in your home; it could be a corner, a room, or a spot outside in the garden. Make it sacred for you to touch magic. Put a boulder there. Make it so that you can touch peace, touch Thầy’s love every time you go there.

You can do the same thing with your loved one who has transitioned. Plant a tree. Make a flower bed. Make a koi pond. Whatever your loved one loved, make that. Then when you practice, do what your loved one loved. My dad loved to fix things. I'm doing some repairs now and I nourish his life in me. You see: the transfer, the transmission, the continuation are very real. Continuation is not imaginary. With the practice we can be continuations of our teacher, our loved ones, our father, our mother.

We offer these things for you to practice and continue. When you feel a little bit overwhelmed, come to the monastery and recharge. Walk where Thầy walked. We are so lucky to have the practice. I feel grateful. Last week, friends came up to cook so the monks and nuns could grieve and do our process. You could feel their love. The Vietnamese want to show their love in the kitchen, and they've been offering all kinds of food to us. There's other ways you can help: come up and help Nikolai fix something around the monastery. We are not just a Vietnamese temple, we're bigger than that.

So, thank you for your practice and your love for our teacher. Thầy is very happy. He's not regretting any moment, because he knows we are here for each other and we have a path. We have our friends, our Sangha. We are very fortunate. Please do what we need to do so that we can carry the magic, the sacred, the legendary energy of Thầy for ourselves and others; we can vibrate with that energy for others. We're definitely going to need it in society. Please continue Thầy in that spirit, always serving the world. He lived his entire life to help the world with every moment, every Dharma talk. It’s incredible, huh?

Your life is for others. Paying tribute to this ideal is really nourishing me right now, more than ever before. Our life is not to satisfy our needs and comforts; we have a purpose other than just to have a good life. There are interbeing and connection. This is the power of Thầy’s life, his message, and our life of service.

Thank you for being here and for your practice.

Excerpts from “Continuing Thầy’s Aspiration,” a Dharma talk given by Brother Phap Dung on January 28, 2022 at Deer Park Monastery during the ceremonies honoring Thích Nhất Hạnh’s passing. The full Dharma talk is available on the Deer Park Monastery Youtube channel.