By Wouter Verhoeven in June 2020

There Is a Place

The closing talk of the Wake Up Retreat in 2016 was beautiful. Brother Phap Dang ended his talk with these words—spoken with a voice like honey, as if the Buddha himself was speaking:

There is a place. There is a place of light.

By Wouter Verhoeven in June 2020

There Is a Place

The closing talk of the Wake Up Retreat in 2016 was beautiful. Brother Phap Dang ended his talk with these words—spoken with a voice like honey, as if the Buddha himself was speaking:

There is a place. There is a place of light. There is a place of true love. There is a place of compassion, loving kindness. There is a place of peace to reign, to settle. And you should go there. You know how to do it.

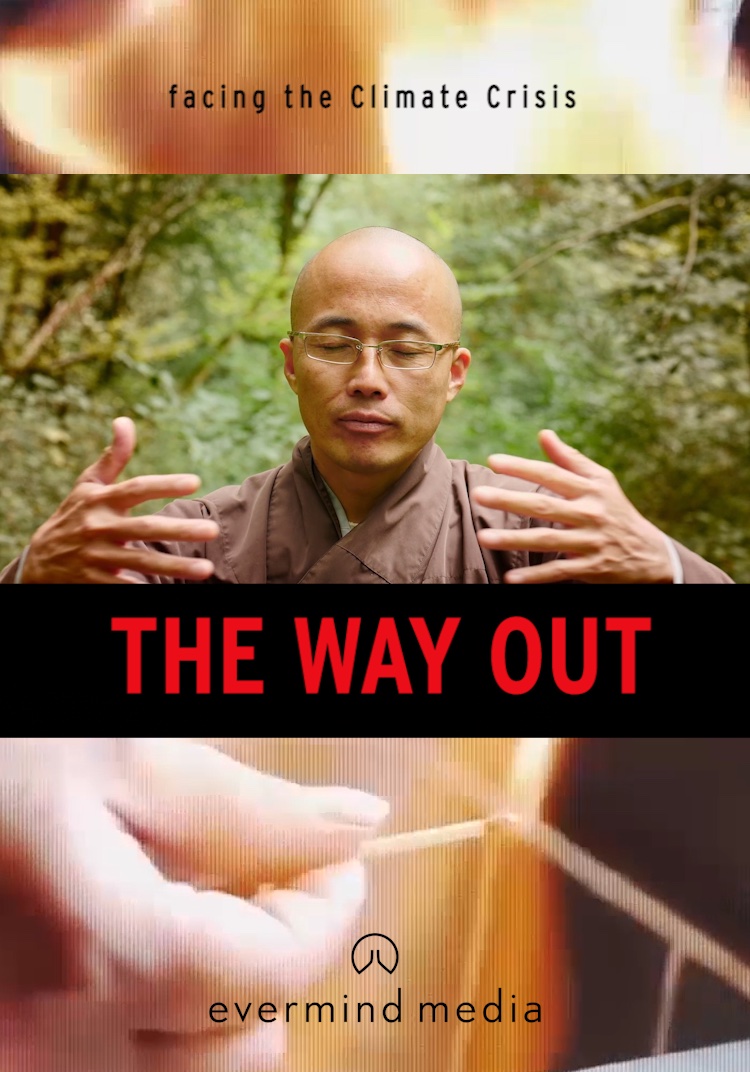

My film editor chose to put these inviting words at the beginning of The Way Out—an urgent film about the climate crisis, activism, and mindfulness—a film born out of the Wake Up Retreats from 2016 to 2018.

Brother Phap Dang said: “And you should go there. You know how to do it.” But is that so? Do we know this place of light and love? Do we really know how to get there?

Paradise

In the middle of winter in 2015, half a year before Brother Phap Dang spoke his inviting words, I had heard from the monastics that a Wake Up Earth retreat was being organized—the first in many years. I responded, “We should film that. We should definitely film that.” I envisioned five hundred young people living in harmony with each other and with the Earth, in the setting of a heavenly Plum Village summer paradise. I could not think of a better example for the future of humanity.

Winter and spring passed. The time for the retreat arrived. Young people from around the world gathered at Upper Hamlet and erected their camp for Wake Up Earth in August 2016.

In the opening talk, Brother Phap Linh said, “This can become a legendary retreat.” And so it was, just as I had imagined: young people living together as if no problems existed, breathing together, working on the Happy Farm together, sitting in silence together, celebrating the wonders of life in every moment. My camera and I registered it all, and we were part of it. During that week, I came to this simple understanding: what I see and feel here is the simple truth of life, and that truth is one of interbeing, of deep connection.

We are not separate selves. Once we live like that, according to that truth, we can find happiness and fulfilment. Living in togetherness, in harmony, we don’t need much. Life is perfect as it is. No more running, no more anxiety, no more searching. We have arrived. We are home.

Six months later I contacted Dutch television. I actually had been seeking funding for another film project—about an ex-general from the Liberian civil war—but I also shared some footage of life in paradise that I had recorded. The commissioning editor was directly taken by the quality and beauty of the footage. But she said she was “not really interested in paradise, nor is the Dutch viewer.” I was surprised. Isn’t it a strange contradiction: we are all looking for happiness, for peace of heart, for connection and true community, but once you show it and can prove with images that it exists, the first reaction you receive is “no thanks, no interest in paradise.” Why is that?

The rule of cinema is that it should contain drama, an overcoming of challenges by heroes and heroines. That also means film should reflect life, as life is a continuous story of the challenges we face. Paradise itself is boring—for film. Based on this view, the commissioning editor proposed that I follow some of the young people filmed in Plum Village back home, and see how they maintain the practice in their daily life, challenged by the difficulties they face.

The Challenges We Face

Yes, we can’t deny it any longer. We all face big difficulties these days. The Amazon is burning, and Greta Thunberg has been crossing the Atlantic by boat, while the climate crisis and the sea levels are still on the rise. What can we do, how can we act, without burning out?

The commissioning editor and I selected three young attendees to follow in their daily lives at home: a Brazilian banker in London, an activist in Yorkshire, and a body and emotion therapist in Vienna. Then came the challenge of filmmaking itself, how to capture truthful, realistic scenes, along with the bigger challenge: how to visualize what happens inside the protagonists, how to make their emotions and inner processes visible?

I filmed Barbara, the body worker, during one of her sessions with a client. We went out on a glorious winter morning in the snowy mountains just outside Vienna to reconnect with nature. I followed Leonardo, the banker, in his daily life in the city of London and during his study of sustainability in Cambridge. And I visited Eddie at an improvised water protection camp near his hometown in North Yorkshire, where he and his colleague activists were building up a resistance against the fracking industry—a new kind of fossil fuel extraction.

Eddie was well aware he and his friends needed spiritual support and practices to remain nonviolent in situations where the seeds of violence are watered easily. So he had invited the Plum Village monastics to come and support him and his friends before their campaign would really start. It was August 2017, summertime in Europe, but I hardly slept my first night in a simple tent and sleeping bag because of the damp cold North Yorkshire field. I knew Eddie and his friends had been staying there eight months already, during a cold, snowy winter with lots of rain and mud, without running water, bathrooms, or any luxuries. My immense respect touched the skies.

There is a place. There is a place of light. There is a place of true love.

During those days of retreat and inner preparation, Eddie, his anarchist friends in the camp, and some interested visitors, guided by a small group of monastics, practiced mindful walking, mindful sitting, and eating in silence together. On one of the evenings Sister Annabel gave a sacred talk. The setting was a wooden cabin built of pallets and scrap wood, lit by candles. “We don’t hate those people,” she said, referring to the people of the fracking industry. “We don’t hate those people who are looking for a direct profit in their lives now. Maybe they have some blindness, and are not able to see.”

I say “a sacred talk,” because Sister Annabel invited us to look deeper, with eyes of compassion, and act accordingly to live our lives from a place of deep love and wholeness, something we easily forget while facing our challenges. The wholeness, connection, and truth of interbeing of the Plum Village paradise seemed far away as I filmed Barbara in the cold streets of Vienna, Leonardo coming back from his work, tired in the Tube, and Eddie in his verbal and physical battles at the fences of the fracking site.

Is paradise on Earth only possible once a year during the summer Wake Up retreat? I know every one of you knows the answer is no. We can be happy, solid, fresh, and free, facing the challenges in front of us, but we need to know how to do it. In the film The Way Out, Brother Phap Huu shares:

Your breath is your best friend. It is your companion on the spiritual path. Wherever you are, you have a way to practice, because you are still breathing. You don’t have to be in Plum Village, you don’t have to be in the meditation hall, in order to “meditate.”

My challenge ahead was to create a compelling story out of a hundred hours of film footage. And I can tell you, that is not an easy job. So I, too, am happy to know the practice, to come back home to my breath when I am getting lost. I am happy somebody told me how to find the path home. Working with my editor, my composer, and some additional advising eyes, including those of the commissioning editor, we were able to realize the film The Way Out—inspired by Thay, the Plum Village community, and the lives and actions of the “Wake Uppers.” The art of filmmaking, you see, is also community work.

Difficult filmmaking choices had to be made along the way, such as cutting one of the three protagonists from the film. The footage shot in Vienna was not compelling enough for my editors; they could not connect to it emotionally. A simple but hard fact. Also hard was telling Barbara, but luckily she could accept it without hurt and let it go. She knows the path home too.

Today

Today, parts of the Amazon jungle, once a place of true community, have been destroyed. Today, youth around the globe are holding school strikes on Fridays. Today, what can each of us do as we face the climate crisis? When American bombs fell on Vietnam and Agent Orange set the jungle and people on fire, Thay did not stay on his cushion with his eyes closed. He stood up and acted, working solidly, diligently, relentlessly for peace.

What can we do, how can we act, for peace on Earth today? Thay has a revolutionary proposal for facing the climate crisis. “The way out is in,” he states. “The way out of climate change is inside each of us.” In the film The Way Out, we follow the Brazilian banker Leonardo and the British activist Eddie during stressful times in their lives.

Will they be able to save the Earth—beginning with(in) themselves? Will they be able to cool down their personal, burning afflictions? Thay has shown them, and all of us, the path home, a way for a different future to be possible.

There is a place of compassion, loving kindness. There is a place of peace to reign, to settle. And you should go there. You know how to do it.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM WKUP.ORG.

Wouter Verhoeven is a filmmaker from the Netherlands and a mindfulness practitioner in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh. Since 2013, he has made films with the Plum Village monastic community. His deep aspiration is to share the mindfulness teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh through films online.