By John Beaudry

I was standing on a narrow sidewalk, bent over, putting a small bandage on a cut my sandal keeps making in the top of my right foot.

The bus that would take us the remaining distance to the island and the temple had not arrived yet. So I had bought some bandages from the small store next to the bus stop.

Standing on the sidewalk,

By John Beaudry

I was standing on a narrow sidewalk, bent over, putting a small bandage on a cut my sandal keeps making in the top of my right foot.

The bus that would take us the remaining distance to the island and the temple had not arrived yet. So I had bought some bandages from the small store next to the bus stop.

Standing on the sidewalk, I put my foot on the store step, bent forward and concentrated on ending the little pain that had been present since early that morning when we had begun our journey from the city to the island.

On the first part of the journey, I had been focused on the koan I always carry in my mind. The strain of pushing against the barrier of the koan, of trying to close the space between it and my mind, merged with the irritation of the cut. The pain intensified the always-present feeling that I lacked sufficient ability to break through the barrier of the koan, that breaking through was impossible. Still, I held onto the koan as fiercely as I could.

Now, I finished attaching the bandage to the foot, checked it—and then realized that there was a head next to mine that also seemed to be looking at my foot. I straightened up to see an old, weathered woman standing next to me, bent over forward past a ninety-degree angle, with her hands clasped behind her back. She was trying to pass through the space between the store wall and me and was bent over because she could no longer stand up straight. I took my foot off the step, opening the space wider for her to pass through.

As she walked slowly past and away, I watched her, trying to see the cause of her present condition. The effect of her past struggles had been to push her dangerously beyond the limit of her physical ability. Past suffering had led to present suffering.

Her hands were the highest point on her body, resting way down her lower back almost directly over her legs. Those hands, I speculated, had carried baskets of vegetables, or worked rice fields, or pulled loaded carts behind her. In that moment, though, the hands’ purpose was to provide balance for walking, and to keep the arms out of the way: If she unclasped her hands, her arms would hang down in front of her legs, dead weight with nothing to support them. So, she held her arms and hands as far back as she could and let her legs carry them.

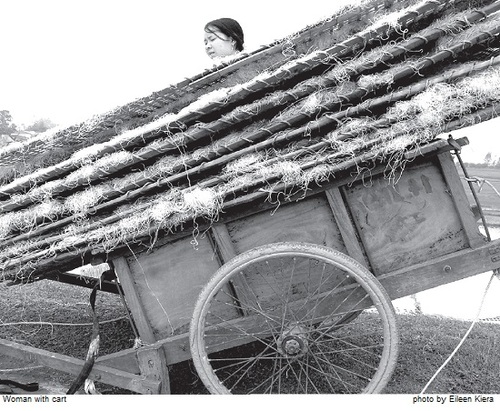

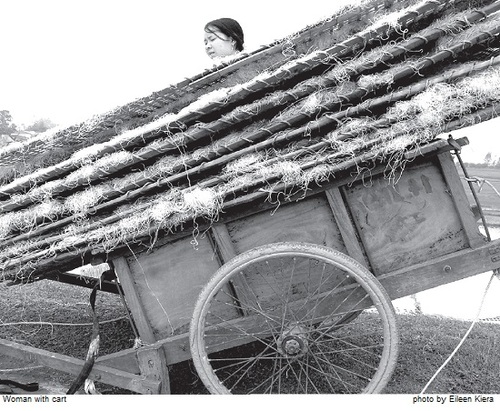

She reminded me of the old men and women in Seoul, where I live, who pull rustic, wooden carts behind them, collecting loads of cardboard and other recyclables, often piling them high above their heads. To me, the weight of the load looks like a lot more than they can handle, pulling the carts up resistant hills, down obstacle-filled alleys, through dangerous street traffic.

When I’m out walking the back road in the mornings, pushing against the barrier of the koan, I pass the cart pullers, often walking in the opposite direction. As we approach each other, their physical struggle is obvious. But there is something else as well, something underneath or behind their suffering that eludes my perception. What is it? In the moment we pass each other I try to cross the space between my understanding and their experience, and I fail.

They walk bent forward, arms behind, hands holding on tightly to the metal bar.

Walking at a slow, determined pace, the cart pullers seem to be concentrating only on the essential: a firm grip, the next step. Looking straight ahead, apparently undistracted by sights and sounds around them, and appearing to rely on intuition to find what they are looking for, they pull against the weight of their load. Are they really that single-minded in their purpose?

To me, their work seems possible only for people of greater physical ability—stronger, younger people. Month after month, on hot days and cold days, they walk their path. It may be that some dare to pity them. But, looking closely at them and seeing what they do, in those fleeting moments, I rediscover compassion and renew awe in my life, the same experience I had upon seeing the old woman who seemed to be looking at my foot.

Connecting to the Source of Compassion

After the old woman passed out of sight the bus came. And soon after that we crossed over the bridge to the island and arrived at the bottom of the road that led up to the temple. We walked up the steep hill at a slow but determined pace, and I noticed as we walked that the bandage was holding, protecting the cut.

At the top of the hill we passed through the old stone temple gate, headed for the main Buddha Hall, went in, and as we always did upon first arriving at a temple, performed the bowing ritual. As I bowed before the statue of Buddha, the weight of the koan, the weakness of my ability, and the strength of the barrier all bowed with me.

After a last bow, I stepped out of the temple door, putting my left foot in my sandal. And as I bent down to check the condition of the bandage on my right foot, I thought of the old woman at the moment when she had passed between the store wall and me. But this time I saw the moment clearly; this time I could see into it as it expanded in my mind.

The moment deepened until it merged with my whole being. In that one moment that seemed to extend forever, I saw deeply into the simple and awesome truth of the moment when the old woman passed between the wall and me, and at the same time into the mystery of the cart pullers.

This moment merged with that moment in a birth of clarity, and I connected to the source of my compassion for them, and my awe. I understood: There are people all around me who are doing the impossible. And in that moment I shared their burden, their suffering and their strength. There was no space between us.

Intuitively, I turned my head from the bandage on my foot to the direction the old woman’s head had appeared from—and saw the smiling face of a monk who was walking toward the Buddha Hall to welcome us. I slid my right foot firmly into the sandal, stood up straight, clasped my hands behind my back, and walked slowly forward to meet him.

John Beaudry has taken the precepts but continues to search hermitages deep in the Korean mountains for an old master to take as a teacher. He lives in Seoul.