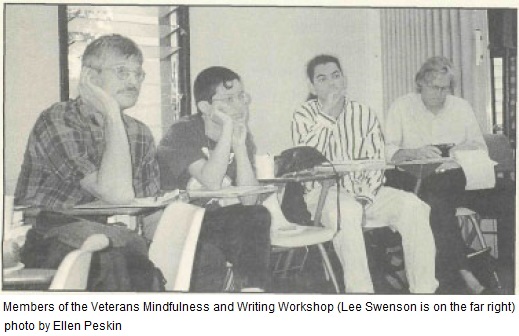

By Lee Swenson

When Maxine Hong Kingston asked me to join the Vietnam War Veterans Writing Group, I hesitated for a few months. The group was a real mix—Vietnam combat vets, stateside draftees, nurses, widows, medics. All wanted to write out their stories. It was hard to imagine reliving those intense days and walking back into those battlefields, terrain laden with buried mines, ready to explode in heart and mind. I also feel tender about my old moralizing voice coming back,

By Lee Swenson

When Maxine Hong Kingston asked me to join the Vietnam War Veterans Writing Group, I hesitated for a few months. The group was a real mix—Vietnam combat vets, stateside draftees, nurses, widows, medics. All wanted to write out their stories. It was hard to imagine reliving those intense days and walking back into those battlefields, terrain laden with buried mines, ready to explode in heart and mind. I also feel tender about my old moralizing voice coming back, a voice with an edge I wanted to keep at rest. I was not sure I could keep calm while speaking my truth about nonviolent anarchism, and I was not sure I wanted to go back into the endless debate between those who went to war and those who chose not to. Yet, how could I resist?

As I went to the monthly meetings, I began to know individuals—a medic, a pilot, a widow, a river patrol point man, a vet coming in from 20 years of living on the streets. Each of us had a separate reality, and now we were all tied together. I saw how hard it was, and is, for the vets to see differences within the antiwar movement, to see individuals making a choice, willing to suffer, to do prison time, to be written out of their families for refusing to kill.

Every month for three years, the Veterans Writing Workshop met for a Day of Mindfulness facilitated by Maxine Hong Kingston and members of the Community of Mindful Living. We began with a bell, heard again and again throughout the day, to calm, to still, to breathe. When we read our day's writing to the group, we found that by remembering to breathe we could do and say nearly anything. After the opening bell and meditation, we went around the circle and added a voice to the community. We were breaking the ice of twenty-five-year-old thoughts and feelings.

At the center of the day, we wrote in community. Maxine suggested an idea, and after discussion, we went to different parts of the room or outside. We wrote for the next few hours, side by side, separate, yet together. Like meeting a grizzly bear on the trail, the electricity of producing together got our undivided attention. After lunch, we read aloud what we had written.

At moments, hardly anyone could breathe as the stories spilled out: buddies killed, body bags zipped up, sheer fear in battle still deep in the bone, coming Stateside, survivor's guilt, rehab drudgery, going to the Wall and finding the name of a platoon mate or husband, leaving a widow's letter and a daughter's baptism gown, never to see her father. There have been few stories from draft resisters and nonviolent activists, and we had many to tell. I wrote about the virtues of nonviolence and why "we" resisted the war. I wrote about a small boy milking the family cow in an Indian village, who meets Gandhi on his way to the sea to commit civil disobedience by gathering his own salt during the Great Salt March. The boy dreams of joining the Freedom Movement. I wrote and read aloud about being in Santa Rita Jail over Christmas 1967, and how Martin Luther King, Jr. came to visit Joan Baez and the rest of us the day after we "offenders" were released. King was assassinated just three months later. In January 1968, we heard on the jail radio that Dr. Spock and six others were arrested for aiding and abetting draft resistance. It was a conspiracy not to kill.

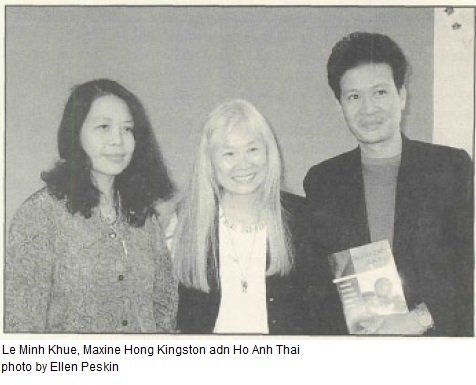

Great veteran writers and National Book Award winners Tim O'Brien and Larry Heineman spent a day with us. One of America's truly great short story writers and peace activist Grace Paley came for an afternoon. We also had a day with Vietnamese soldiers (the "enemy"). Le Minh Khue had spent her youth on the Ho Chi Minh (Song My) Trail. Her greatest fear on the Trail was of American pilots just hundreds of feet overhead, releasing napalm or fragmentational percussion bombs. She could almost see their faces and look into their eyes. Now they were face-to-face, pilot and foot soldier. They met, touched, and hugged.

We edited together. We brought copies of stories, lay them on a table, and gave and received criticism. It was scary and very moving. Grace Paley said, "Editing is taking out the lies!" This group was a great lie detector.

We did bookstore readings and a public radio show on Veteran's Day. Some of us were men who had lived on the streets for years. At Black Oak Bookstore, Tom, blinking, twitching, and agitated bellowed out, "I useta get kicked outa Black Oak, now I'm reading here!" Maxine held steady through all this, month after month—encouraging, criticizing, and firmly prodding us. Now Maxine is taking a rest from group organizing to finish her own peace novel.

An anthology is in the works. Our task is to keep writing, to find the stories in this great flow of memory, and to bring them to the surface. There are many more stories to come.

Lee Swenson, a longtime peace activist and community organizer, lives in Berkeley, California.