The Roots of Our Community

By Adrienne Minh-Chau Le

The following article is an excerpt from a presentation entitled Touching the Roots of Our Community, offered by Adrienne Minh-Chau Le and hosted by the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation in the spring of 2020.

The Roots of Our Community

By Adrienne Minh-Chau Le

The following article is an excerpt from a presentation entitled Touching the Roots of Our Community, offered by Adrienne Minh-Chau Le and hosted by the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation in the spring of 2020. The information was collected through memoirs, in-depth interviews with Sister Chan Khong and a dozen of Thich Nhat Hanh’s first students in Vietnam, and archival study in Vietnam and the United States.

Like so many others, I consider Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay) my teacher because of the practices of mindfulness, ethical behavior, and compassionate action that he embodies. We know that Thay only teaches us what he himself has lived and experienced. Here I want to take us back to the beginning, before Thay became the world-renowned teacher he is today, to the years that led to the writing of the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings and the ordination of the first six members of the Order of Interbeing in 1966. By examining the history of our community in Vietnam, we can connect with the tradition that we carry, understand our roots, and see how we are meant to grow as a spiritual community.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Early Vision

In his early life, Thay witnessed his country go through enormous transformation. He was born during the French colonial era, in 1926, and was nineteen years old when the war for independence began. He was twenty-eight years old when France was defeated and Vietnam was split into North and South, the divide that was the basis of what Americans call the Vietnam War.

Through his writings in the 1950s, we can see that Thay was deeply concerned about the role of Buddhism in the modern Vietnamese nation. He was a strong advocate for socially engaged, nationally unified Buddhism. He and other young, progressive monks tried to push the Buddhist hierarchy to create a national program that would address the needs of their divided country and work toward peace, but the elders dismissed this vision. “We were considered rabble-rousers who only wanted to tear things down,” Thay reflected in his journal. Eventually, Thay was removed from his position as editor in chief of Vietnamese Buddhism, the official journal of the General Buddhist Association, and the publication was discontinued.

This apparent rejection strongly impacted Thay. He came to realize that he could not rely on existing Buddhist institutions and its leaders to enact the reforms he believed were necessary for peace, reconciliation, and the future of Vietnam. Instead, he turned toward young people as the force that could renew socially engaged Buddhism for the twentieth century.

The School of Youth for Social Service

Founded in 1964 as a part of Vạn Hạnh Buddhist University in Saigon, the mission of the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS) was to train college-aged students to lead rural development projects that would improve the everyday livelihood of villagers. In his own words, Thay wanted SYSS students to be “equally knowledgeable about social concerns and religious teaching” and to “understand effective methods to combat poverty, disease, ignorance, and misunderstanding.”

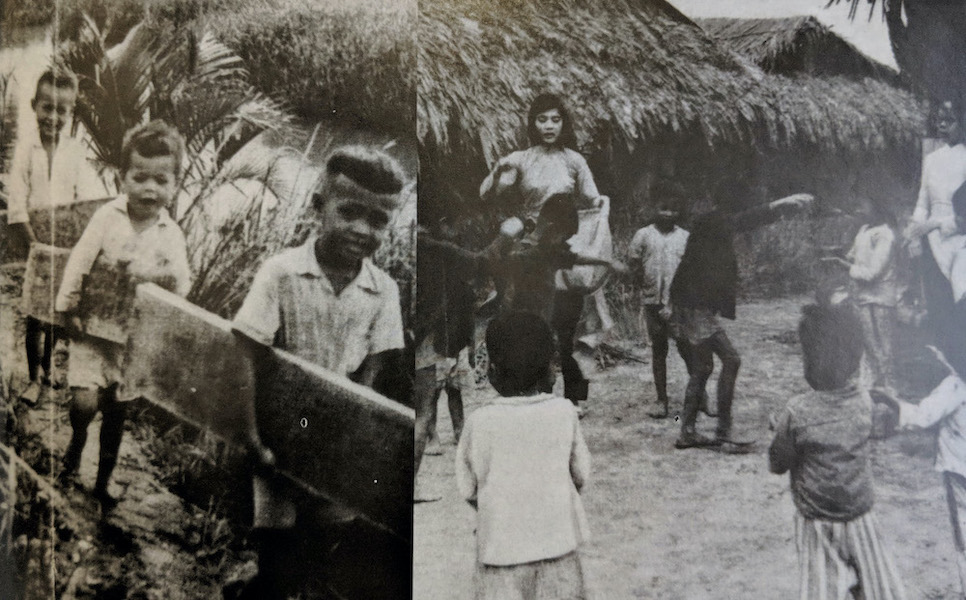

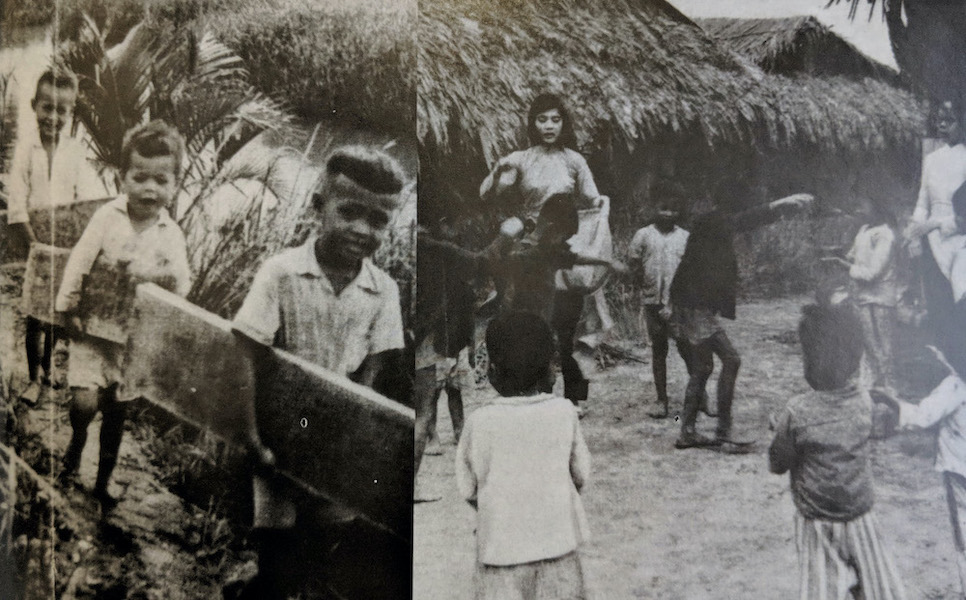

SYSS students were trained in four key areas: childhood education, medical care, household economics, and community organization. Each class of about two hundred included novice monks and nuns as well as laypeople. After two years of coursework, with hands-on training between academic semesters, student volunteers were assigned to villages where they would live and lead development projects for six months to two years. They began by teaching children how to read, play games, and sing folk songs while building trust within the community. Eventually, they would offer basic medical care, teach handicrafts and farming techniques, dig wells, organize cultural events, and construct schools, houses, bridges, and other facilities.

Importantly, this work was carried out as the war raged on. In addition to their everyday activities, students organized emergency relief missions, delivering truckloads of food, clothing, and medicine to areas devastated by floods and intense fighting. They consoled survivors and rebuilt villages multiple times after repeated bombings. During the Tet Offensive in 1968, thousands of people from the surrounding area took refuge in the school’s campus on the outskirts of Saigon.

The polarized landscape of the war posed severe dangers for SYSS students and staff. Because they were not politically affiliated with the Communist Front or the Saigon government, they occupied a middle zone where they could be mistaken as a tool of one side or the other. As one former student put it, “After starting down this path, I saw that it was even more dangerous than going down the other path [of joining the army]. By following our teacher, we got caught in the crossfire. Both sides wanted to kill us.” The SYSS was attacked several times by unidentified people with guns and grenades, resulting in the permanent disappearance of eight students and the killing of thirteen, while dozens of others were injured and harassed. Today, the graves of SYSS students and staff killed during the war can be found where their campus once stood, at Phap Van Temple in Saigon.

International Reach and Impact

Seeing that the war in Vietnam was entangled in international politics, Thay knew that in order to help establish peace within his country he would need to speak with people abroad. While the SYSS continued its work, he turned his attention to international efforts for peace.

In 1966, Thay traveled to the United States for a peace tour organized by the Fellowship of Reconciliation. What was meant to be a three-week tour turned into several months of international travel. Thay visited nineteen countries and poured all his energy into conveying the situation in Vietnam and the urgent need to end the war. In addition to public talks, he connected privately with prominent figures including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Pope Paul VI.

Sister Chan Khong also played a vital role in these international advocacy efforts. While conducting much of the SYSS organizing work in Vietnam, she sent information abroad about the needs of the school as well as other Buddhist efforts toward peace. This information helped people around the world understand what was happening in the country and offered a way for them to contribute directly to development and relief work in Vietnam.

Together, Sister Chan Khong and Thay were firebrands for peace, taking a radical and dangerous stance that they nevertheless felt was right. Those who spoke out against the war in South Vietnam were labeled as Communists; many were harassed, jailed, tortured, or killed. Thay’s friends and colleagues in Vietnam advised him not to return home after his tour because his life would be in danger. Due to her anti-war organizing, Sister Chan Khong was jailed twice and constantly monitored by the police. She eventually left the country in 1969 out of concern for her safety and a desire to help Thay with his work internationally. Intending to be gone only a few months, Thay and Sister Chan Khong were exiled from Vietnam for almost forty years. They turned exile into an opportunity to plant seeds of Dharma in new soil, to give rise to the global community we have today.

Conclusion

Amidst the polarized landscape of war, in the face of violence and the deaths of their loved ones, Thay and his students carried on with incredible determination. As one SYSS student wrote, “We endured and tried to let go of the hatred and pain that arose from having… our friends killed. Their graves on the school grounds always reminded us and guided us on the path. We had to keep going, to carry out the ideal that we all shared.”

My hope in studying and writing about this history is to enable our worldwide Sangha to touch these roots, to know where our practice comes from and understand the tradition that we now carry. We were never meant to practice just for ourselves. I hope that we will strive to embody the spirit of fierce compassion and love in action that Thay’s first students did. They put their lives on the line in order to build a beautiful future in the middle of war. As the descendants of this lineage, what should we be doing for our communities, our society, and our world today?

The Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation would like to offer a deep bow of gratitude to our beloved community for helping continue our healing, noble, and brave tradition. Over the last year, as the pandemic left our monastics with no choice but to close the practice centers to the public, you have helped keep the flame of our tradition alive by supporting them and the centers. Thank you.

Adrienne Minh-Chau, True Manifestation of Goodness, is a PhD candidate at Columbia University, New York, US. Her research is focused on the Buddhist movement during the Vietnam War, including efforts that gave rise to the Order of Interbeing and eventually the Plum Village community.