“A Letter across the Divide”

By Marc Andrus on

It is important to first understand the significant barriers—religious, political, and social—that lay between Thích Nhất Hạnh and Martin Luther King Jr., before we can understand how the successful bridging of this gap highlights the precious quality of their friendship. From today’s standpoint, these barriers might not appear formidable, but this is almost certainly,

“A Letter across the Divide”

By Marc Andrus on

It is important to first understand the significant barriers—religious, political, and social—that lay between Thích Nhất Hạnh and Martin Luther King Jr., before we can understand how the successful bridging of this gap highlights the precious quality of their friendship. From today’s standpoint, these barriers might not appear formidable, but this is almost certainly, in part, due to the efforts of King and Nhất Hạnh, along with many others, that changed the social and religious conditions in the United States such that friendships like theirs might flourish more easily. In the 1950s and ’60s, friendships across barriers of race and religion were not only uncommon but could prove dangerous.

For instance, consider the experience of Opel Lee, the nonagenarian advocate for making Juneteenth a Federal holiday. Lee’s parents moved with their young daughter into a white neighborhood of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1939. The realtors who sold Lee’s parents their new home told them that they would encounter no problem with their white neighbors. Instead, within a week and on the occasion of Juneteenth, a mob estimated at 500 people surrounded the house, invaded it, dragged the furniture into the street and set the Lee’s possessions ablaze. And even though the efforts of King, Nhất Hạnh and many others have improved race and religious respect in the United States, the instances in the twenty-first century of anti-Muslim violence and violence against Asians yields current testimony to the enduring power of prejudice.

By no means was Buddhism a new topic and presence in the United States by the middle of the twentieth century. D. T. Suzuki and Soyen Shaku, for example, helped to spread a version of Zen in America throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Suzuki especially promoted an experience and practice-based version of Zen that appealed to qualities that resonated with American ideals: a “no nonsense,” accessible religion that was often called no religion at all, but a philosophy of life. The practice of Zen required determination, not adherence to creeds and dogma. Zen Buddhism accorded with William James’s emphasis on religious experience, not doctrine, as the fount of subsequent tradition. The Beats picked up on Zen, partly through the influence of California poet Gary Snyder, a sponsorship that brought it into popular culture.

Despite this, American exposure to Buddhism was still comparatively fresh. The eloquent Alan Watts gave his popular lectures on Zen and other Buddhist and Hindu themes on the Berkeley radio station KPFA from 1953 to 1962. Watt’s widely-read book The Way of Zen was published in 1957. Shunryu Suzuki founded the San Francisco Zen Center in 1962, but it wasn’t until 1969 that he established Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, in Big Sur, California, one of the first Buddhist training monasteries outside of Asia. His popular book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind was not published until 1970.

Likewise, Tibetan Buddhism, and particularly the Vajrayana form of Buddhism, made its spectacular entrance into the United States with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche only in 1970. Institutions that Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche founded—such as his Shambhala meditation centers, Naropa University, and Shambhala Publications—helped spread awareness about Tibetan Buddhism around the United States and the world.

Seven years later, in 1977, Harvey Cox, a Professor of Divinity at Harvard University, would write Turning East, a retrospective survey of the influx and influence of Asian religions in the United States. Cox’s book has the feel of freshness about it; he is not peering far back in time but is taking a look at the contemporary religious landscape in the United States of the late seventies and some of the preceding decades.* In summary, while Buddhism was present in “the cultural conversation of the 1960s, the coming together in friendship of a Buddhist and a Christian at this time was not a commonplace encounter.

In addition to the relative newness of Buddhism in popular culture, the war raging between the United States and Vietnam could only make the Nhất Hạnh/King friendship more unlikely and potentially fraught. Several sources date the flowering of the anti–Vietnam War movement in the United States to 1965.

Finally, their social positions: Nhất Hạnh was celibate, a monk from the age of sixteen; King was married and a minister. Monasticism, while holding a prominent position in the two largest Christian bodies—Roman Catholicism and Easter Orthodoxy—is decidedly a minority presence in Protestant Christianity, and entirely absent from the most reformed bodies, such as the Baptist Church. The life of Nhất Hạnh would have been foreign and exotic to most Protestants.

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s poem, “Our Green Garden” was published in the New York Review of Books on June 9, 1966, just days after he and King held their joint press conference in Chicago regarding the war. Thus, as their friendship begins, it is founded on the grounds of a war protest that was only starting to gain cultural traction. Nhất Hạnh and King must have summoned thought and courage to cross the barriers of culture, race, politics, and religion to hold this press conference together. Sitting beside one another behind the phalanx of microphones that broadcast their voices, Nhất Hạnh and King were the embodiment of interconnected reality.

“Our Green Garden” touched American readers because it depends on an underlying worldview that is at the heart of the constitution of the Beloved Community: the interconnectedness of all things through love. Love, more than blood, makes family, and the speaker in “Our Green Garden” is in a heartfelt colloquy with his “brother,” someone who has taken up arms against him, despite the fact that they have the same mother (Vietnam). The same distortions that sundered one Vietnamese from another had separated Americans from the Vietnamese, though all were members of the Beloved Community. King and Nhất Hạnh meeting in Chicago was the coming together, the reconciliation of brothers. It is worth reproducing “Our Green Garden” here—it is a beautiful poem that had a far-reaching and powerful effect on the American public and backgrounds the familial relationship between all who are loyal to the Beloved Community.

Our Green Garden Fires spring up at all ten points of the universe. A furious, acrid wind sweeps them toward us from all sides. Aloof and beautiful, the mountains and rivers abide. All around, the horizon burns with the color of death. As for me, yes, I am still alive, but my body and soul writhe as if they too had been set on fire. My parched eyes can shed no more tears. Where are you going this evening, dear brother, in what direction? The rattle of gunfire is close at hand. In her breast, the heart of our mother shrivels and fades like a dying flower. She bows her head, her smooth black hair now threaded with white. How many nights has she crouched, wide awake, alone with her lantern, praying for the storm to end? Dearest brother, I know it is you who will shoot me tonight, piercing our mother’s heart with a wound that can never heal. O terrible winds that blow from the ends of the Earth, hurling down our houses and blasting our fertile fields! I say farewell to the blazing, blackening place where I was born. Here is my breast! Aim your gun at it, brother, shoot! I offer my body, the body our mother bore and nurtured. Destroy it if you wish. Destroy it in the name of your dream— that dream in whose name you kill. Can you hear me invoke the darkness, “When will the suffering end? O darkness, in whose name do you destroy?” Come back, dear brother, and kneel at our mother’s knee. Don’t sacrifice our green garden to the ragged flames that have been carried into the front yard by wild winds from far away. Here is my breast. Aim your gun at it, brother, shoot! Destroy me if you wish and build from my carrion whatever it is you are dreaming of. Who will be left to celebrate a victory made of blood and fire?

It is hard to know what American readers made of the Buddhist cosmological reference, “the ten points of the universe,” but in all likelihood they felt keenly the sorrow of one people being torn apart, as if brothers had forgotten their common origin and become enemies. The grandparents of many Americans in the 1950s and ’60s may have been children in the American Civil War. The grandparents of many Americans in the 1950s and ’60s may have been children in the American Civil War. The grandparents of many Black Americans during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s may have been enslaved children or themselves the children of slaves—people betrayed for generations by their own country. The homegrown American experience of the unity of a people, its interrelatedness, being ripped apart may have surfaced by reading “Our Green Garden.”

On balance, then, there are forces we can trace moving Nhất Hạnh and King toward one another, as well as countervailing forces that would make their friendship unlikely. That their meetings, exchanges, and friendship came forth despite these walls is a testimony to their will, courage, and foresight.

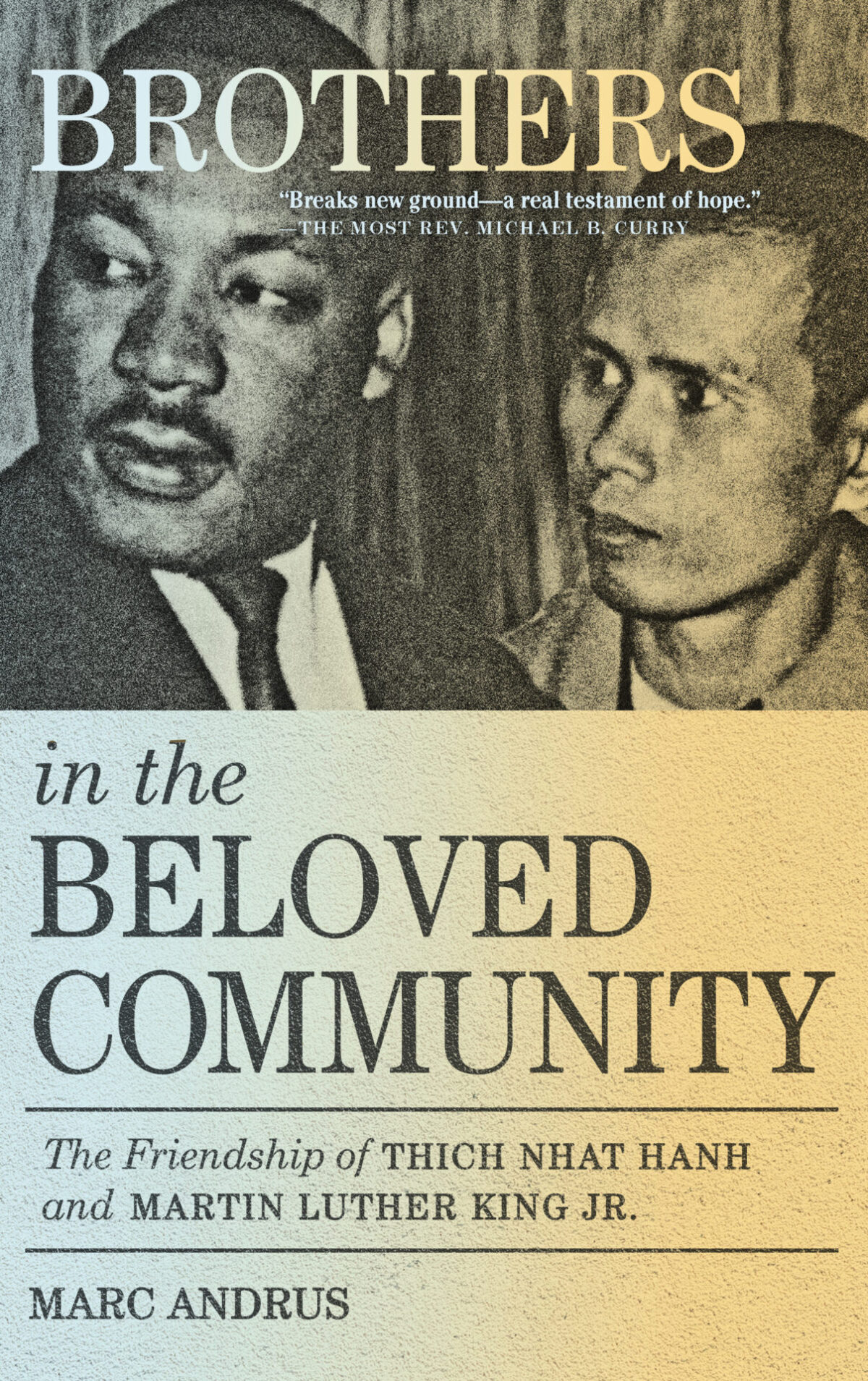

This is an excerpt from Marc Andrus’ Brothers in the Beloved Community. Reprinted with permission from Parallax Press.