By Allan Hunt Badiner

A commentary on the second of the Five Awarenesses: “We are aware of the expectations that our ancestors, our children and their children have of us.”

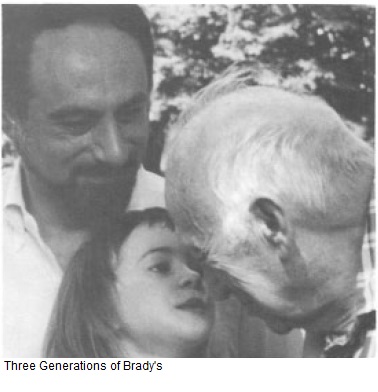

Key to understanding the full significance of each of the Five Awarenesses is to see ourselves not as individuals, but as continuations of all previous and future generations. The second awareness speaks of expectations. What does it mean for our grandchildren or great-grandparents to expect something from us?

By Allan Hunt Badiner

A commentary on the second of the Five Awarenesses: "We are aware of the expectations that our ancestors, our children and their children have of us."

Key to understanding the full significance of each of the Five Awarenesses is to see ourselves not as individuals, but as continuations of all previous and future generations. The second awareness speaks of expectations. What does it mean for our grandchildren or great-grandparents to expect something from us? We all have expectations. We all aspire to have certain experiences, to own or control things, or to be special in some way. And, most essentially, we all expect to be happy, to love and be loved, to be appreciated fully, and to be understood. So much of what we perceive to be our deepest needs depends on the understanding of others.

The happiness or sorrow that our forebears experienced have made deep impressions within our bodies. In addition to the pattern of hair growth, the color of our skin, and the timbre of our voice, our predecessors transmitted certain tendencies related to our smile, our moods, and even our thoughts. In fact, it is difficult to isolate anything that is entirely separate from our genetic line, ahead and behind us. Every being in the stream of life is conditioning every other being, in both directions of time.

Deep within us are seeds of happiness, wisdom, and love, as well as seeds of unhappiness, anger, and greed. These seeds are not only in our consciousness, but also in our bodies. We inherit many of these seeds from ancestors back through the generations, and then we pass them on to our offspring for continued transmission.

Thay reminds us that we are now in a position to take care of these seeds: "With the practice of mindfulness we can water the good seeds in us and transform the seeds in us that are not so good. If we sow seeds that are destructive to us, then they will be destructive to our children and grandchildren. While our descendants may not be visible yet, they are within us, talking to us. They want us to live in such a way that they won't be miserable when they manifest."

When we fully recognize how our desires condition our offspring, we begin to understand our responsibility. In the Jeta Grove of Anathapindika's Park, the Buddha offered ways we can condition our lives to produce the greatest happiness for a stream of generations. The Discourse on Happiness helps us remember that all aspects of our physical and mental environment condition us and are part of us. Whether they be for trees and flowers or ideas and behaviors, seeds planted now will bring a ripening of healthy conditions in the future.

Even if we are not having children ourselves, we are part of the environment which conditions other parents and their children. When we spend our time with people who behave wickedly or cruelly, we absorb their inclinations. The insights and habits of wise and kind people affect us in subtle yet profound ways. Freely acknowledging and finding ways to honor these friends help us change and grow.

To be happy, it is said that we must cherish our family and all our relations. Undoubtedly, our parents or relatives have disappointed us and caused confusion and pain. Responding to them with cheerfulness and generosity can sometimes feel like a major challenge. But what the "Discourse on Happiness" is trying to tell us is that it's a good medicine for our own suffering as well. This is not necessarily an "Eastern" idea. Native American customs, as well as Christian traditions, urge us to take special care of our ancestors. When we support our parents, we are helping to provide them with the security and freedom from worry that we enjoyed as children.

One elusively simple way to generate happiness is to cultivate our relationship with beauty and to expand the range of what we see as beautiful. Fixation on one object of beauty causes us a lot of trouble. We can realize the beauty of both sexes and all ages, and, doing so, we can see how our prejudices have limited what we were able to see and enjoy.

A couple who practices the second awareness lives in a way that not only satisfies their own spiritual and physical needs, but also realizes the hopes and expectations of their ancestors and future generations. To live in this awareness is to realize what our ancestors wanted to realize themselves, but were not able to. Long deceased or not yet born, their best expectations of us continue.

Allan Hunt Badiner is a Buddhist practitioner and expecting father. He is the editor of Dharma Gaia: A Harvest of Essays in Buddhism and Ecology, and is presently writing a book on Buddhist pilgrimage in India.