Tai Chi and Mindfulness

By Robert Wall

Kids love to move, and they love to investigate. I tried to keep this in mind as I planned a qualitative pilot study to see if combining tai chi and mindfulness practice would hold the interest of middleschool students. This mix of practices not only held their interest, it also produced positive outcomes.

Tai Chi and Mindfulness

By Robert Wall

Kids love to move, and they love to investigate. I tried to keep this in mind as I planned a qualitative pilot study to see if combining tai chi and mindfulness practice would hold the interest of middleschool students. This mix of practices not only held their interest, it also produced positive outcomes.

I conducted this study in 2005 in a Boston inner city middle school where I was doing my nursing training. When the school nurse heard that I was a tai chi teacher, she suggested that I share this practice with the students. Being in a school setting made it easy to offer this class as an elective when kids were in school and had no other demands on their time. I designed a class that lasted one hour and met weekly for five weeks.

In my own practice of tai chi and meditation, I had learned that the body is of prime importance, as it offers many gates a person can go through to discover himself or herself. The Buddhist practice of awareness of the body in the body is one platform for discovering the essential oneness and uniqueness of life. Thay’s teaching emphasizes the importance of the body as a gate to enlightenment. He continually brings us to present-moment awareness of each footstep, each breath, each smile. I wanted to offer my students this practice that could help them in their own self-discovery. I shared what I had mastered: a tai chi form and core skills from mindfulness-based stress reduction meditation.

Love of Movement: Tai Chi

Tai chi is a martial art consisting of a formal and precise series of interpenetrating steps that engender well-being. Tai chi can be challenging to teach; it is not normally taught to children under age sixteen because of the attention and focus required. While yoga, dance, and sensory awareness practices may be more accessible to children and can be fun and full of self-discovery, they may not reach into a place where self-regulation occurs from the simplicity of sitting and breathing, or taking a precise step with correct posture.

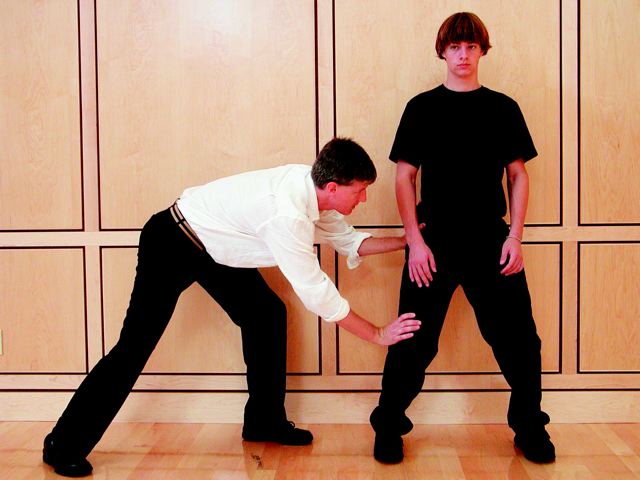

Teaching tai chi to the students provided an opportunity to introduce koans. The use of koans, non-linear stories or questions that can lead to insight, intrigued twelve-year-olds who were learning to manipulate abstract concepts. In one class I offered three boys the koan, “What is the door which is no door?” I showed the boys how to stand in horse stance, an important position in tai chi and chi gong. They made a slight torque of the knees outward and tilted the pelvis so that when I pushed with gradual force sideways on one boy’s hip or knee, the force of my push was directed downward into the earth through his skeletal structure (see photos above). No resistance on his part was needed. No matter how hard I pushed, the boy’s core structure was configured in such a way that the push went into his feet. One boy understood this very readily; when he took any element out of the correct posture, he found he had to use muscular force and effort to resist the push. The koan opened up for him: the effortlessness he felt in non-resistance to the push when he was in horse stance was “the door which is no door.” Koans such as this one directly challenged linear thinking while revealing something the boys could sense physically but not put into words.

Love of Investigation: Mindfulness Practice

At the beginning of each class, I asked each student to affirm that he or she was choosing to be there. I asked them, “What brings you here?” I introduced abdominal breathing and deep relaxation, which incorporated a body scan. I also introduced sitting and listening to a bell to hear sounds with equanimity.

In one exercise, we used an investigatory approach to explore the non-food elements in an apple. One boy, whom I will call Marcus, was particularly reticent to learn anything. When we began looking at the non-apple elements comprising the fruit, Marcus became more attentive. He had never thought about an apple this way before. I touched on the reality of migrant children whose families harvest the apples and who may not have insurance or housing. Immediately Marcus told me he knew what it meant not to have health insurance: his grandmother could never get the medicine the doctor prescribed for her. He had known what it was not to have housing when he and his brother lived for a time in a shelter.

We sliced the apple, heard its crunch, and smelled its fragrance. We were surprised by the coolness wafting out with the sweet smell. Marcus turned the slice in the afternoon sunlight that flooded the second story metal and glass room. He found a vein in the apple. He looked at the back of his hand and saw the veins there. He traced them with his finger and said, “Wow, the apple and me are the same.” After we let that sink in, we took a bite and tasted the sweetness, holding all these elements in mind with each bite.

This project taught practices to children who live in an urban environment that continually exposes them to power and aggression. Even in such a setting, the students made statements that showed they felt increased well-being, calm, relaxation, improved sleep, less reactivity, greater selfcare, self-awareness, and a sense of interconnection with nature as a result of taking the class.

I invite readers to consider offering to children in a school setting a movement practice such as tai chi, yoga, or chi gong in combination with exercises that introduce and encourage mindfulness practice.

Robert B. Wall, Truly Holding Virtue, is a family nurse practitioner and a Buddhist chaplain at Mass General Hospital, Boston. He belongs to the House Sangha of Salem and Marblehead.