By Cathy Cockrell, Louise Dunlap, and Lyn Fine

The murder of George Floyd and systemic inequalities revealed by the pandemic call up centuries of genocide, enslavement, and exploitation. It is lethal and heartbreaking. How in these times can the Plum Village practice community contribute to transforming racial injustice and support wise, skillful, and compassionate action grounded in love—in short,

By Cathy Cockrell, Louise Dunlap, and Lyn Fine

The murder of George Floyd and systemic inequalities revealed by the pandemic call up centuries of genocide, enslavement, and exploitation. It is lethal and heartbreaking. How in these times can the Plum Village practice community contribute to transforming racial injustice and support wise, skillful, and compassionate action grounded in love—in short, create beloved community? As Thay reminds us, “The willingness to love is not enough. If you do not understand, you cannot love.”1

Five years ago in an earlier moment of truth, following the Charleston, South Carolina massacre, some of us as white practitioners found guidance in an article written by Marisela Gomez and Valerie Brown in the Mindfulness Bell. In “The Path of Racial and Social Equity—An Open Heart is Called for Now,”2 Marisela and Valerie invited Sanghas “to actively engage in a process of understanding and building beloved community.” They suggested what are now called sanctuary spaces, encouraging white allies of people of color to create “safe and loving spaces… (for) looking deeply, understanding, and healing from implicit bias and other forms of discrimination” and for understanding “the systemic legacy of racial inequity.” They also encouraged creating spaces “for people of color to heal from the trauma of racial injustice” and “for people of color and white allies to come together to look deeply and engage in healing together.” In addition, they invited the community to “look… deeply at and address… the under-representation of people of color and low-income people in our individual Sanghas and the collective Sangha.”

Launching a White Awareness Sangha

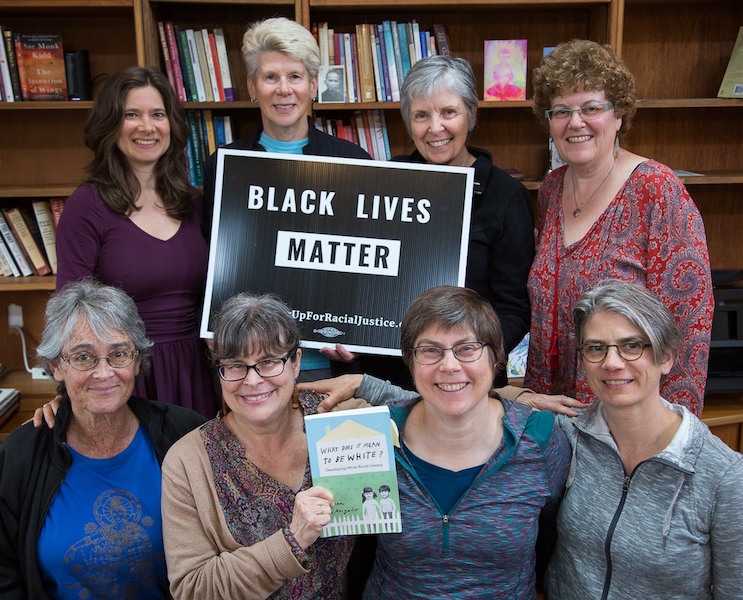

Since that article, Sanghas around the United States and beyond have formed to explore these paths of practice. Here, we share the experience of starting the Deepening White Awareness Sangha in Oakland, California four years ago. We are a small, intimate Sangha that had practiced together in a larger, rigorous nine-week study group for white-identified practitioners facilitated by Order of Interbeing member AJ Johnston. There we looked squarely together at the US racial history many white people haven’t learned and used mindfulness practices to build a foundation of trust so we could transform and heal the pain and discomfort that learning this history brought up for us. Afterwards, some of us continued as a support group, and several, including AJ, met as a Sangha.

Twice a month, the Sangha gathers for sitting and walking meditation and for Dharma sharing, understanding we are here to speak from the heart about daily racial injustices and recognize the role we play. AJ talks about not turning away from the pain we feel about racial oppression in society or in ourselves, but not staying stuck in it either. “We have to have a kind of fierceness or persistence to keep looking,” she says, “even when it’s painful. Then to know when to step back and be more gentle with ourselves and with others.” Her practice with the Sangha has helped refocus her commitment to this work. She says that in the past, her motivation came from a sense of justice. But she’s come to see that also what she’s doing now has to do with her own liberation and well-being, which is connected to everybody’s well-being.

Another Sangha member, Louise Dunlap—an Order of Interbeing member and a writer—is currently completing a book about her ancestors’ role in the conquest of Native Americans in California’s Napa Valley. She encourages touching our white ancestors, especially those whose racial views may provoke feelings of shame in us. AJ recognizes those feelings and says she’s done the research to know that some of her ancestors were enslavers. She recalls Thay’s teaching that transforming ourselves, we transform our ancestors. “When I heard him say this,” she says, “I felt a deep resonance of truth, even though intellectually I couldn’t understand it.” When AJ first started leading white-awareness classes in 2013, she shares, “I thought if people knew my background, both black people and white people would dislike me. That was a tape I had in my head, that I had to hide this.” In fact, she says, “It’s been liberating to tell the story.”

Especially when we break these deep silences, Dharma sharing can give rise to strong emotion in speakers, listeners, or both. We do our best to create an emotionally safe space for going to places that might feel scary, uncomfortable, shameful, or vulnerable, refrain from blaming and shaming language when we speak, and be mindful of judging others or ourselves as we listen. This has been an edge for Louise. She recalls struggling for years to invite other white people into this inquiry, but often feeling blame toward those who didn’t share her sense of urgency about addressing racial discrimination or thought they didn’t need the work. Now she views her blaming as watering seeds of dualism. “At some point,” she says, “I realized that if I could address the racial conditioning in my own mind, I’d be free to speak to anyone with equanimity and skillfulness. Sharing this dilemma with the Sangha helped me touch loving feelings for other white practitioners who are just beginning to learn about race. And that is big for me.”

Our Dharma sharing has gradually become more trusting and heartfelt. One person shares about a racially charged incident in their neighborhood, another about a difficult conversation about race with a family member. Another shares something about their ancestors. One person tells of a moment when they spoke up against discrimination—or didn’t, but wished they had. A person might reflect on a time when they said something unintentionally hurtful to a person of color, exploring with the support of the Sangha how to begin anew.

Through role plays, we have practiced responding to micro-aggressions we observe. Members often share about something they would like to do, or are doing, in the world to challenge systemic discrimination. We have shared our experiences with the many deep courses and talks offered by Dharma teachers Sister Peace, Kaira Jewel Lingo, Larry Ward, and Valerie Brown.

While we refrain from cross-talk in Dharma sharing, we do sometimes ask Sangha members to reflect back to us what they have heard us say and occasionally ask for guidance. Mainly, however, the Sangha practices deep listening. As our hearts open, insight and softening, healing and deepening solidity occur.

Practicing with a Sangha

As Sangha, we do our best to acknowledge and support each other in recognizing our own reactivity or defensiveness, urgency, internalized superiority, or other manifestations of white supremacy culture. We recognize and embrace with spaciousness that we are in different places on our life journeys and our racial identity journeys. Practicing together in an emotionally safe and loving space rather than in isolation allows us to heal and transform seeds of racial conditioning in the storehouse consciousness. It allows us to come from a place of love and touch interbeing.

We become bolder and more skillful in challenging systemic inequity. “Trying to fight a huge system of racial oppression is very disheartening to do alone,” says Sangha member Max Heiliger, who is active in Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ). “We can all do incremental things in terms of our personal relationships,” she says. “But to contribute toward systemic change, I think we have to do it in a group.” The inner and interpersonal practice supported in Sangha creates a strong foundation as we engage in action to transform systemic racial injustice.

“Thay says the next Buddha may come not as an individual but as a Sangha, a community practicing mindful living,” AJ notes, “The Deepening White Awareness Sangha is a Buddha for me, where I feel a deep sense of truth-telling in community around difficult topics. A container gets created where it’s okay to name those places where we’ve mis-stepped around race. For me that’s quite healing.” Creating a safe space for deepening white awareness is healing for everyone.

1 https://www.inquiringmind.com/article/1002_41_thich-nhat_hanh

2 http://arisesangha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/gomez-brown-path-of-racial-equality-final-pdf.pdf

Cathy Cockrell, Clear Caring of the Source, is a longtime member of the Potluck Sangha in the San Francisco East Bay and a member of the Deepening White Awareness Sangha.

Louise Dunlap, True Silent Teaching, co-facilitated the Mindfulness, Diversity and Social Change Sangha in Oakland, California for many years and is a founding member of the Deepening White Awareness Sangha.

Lyn Fine, True Goodness, co-founded the Mindful Peacebuilding Sangha, is a Dharma teacher based in the East Bay, and serves on the advisory board of ARISE Sangha.

All are members of the Deepening White Awareness Sangha.