By Thich Nhat Hanh in October 2010

Dharma talk at the European Institute of Applied Buddhism

June 11, 2010

During the war, Thich Nhat Hanh was moved to find an appropriate and beneficial way to bring the teachings and practices of the Buddha directly to the real suffering of the people. In 1966, the Tiep Hien Order, or Order of Interbeing,

By Thich Nhat Hanh in October 2010

Dharma talk at the European Institute of Applied Buddhism

June 11, 2010

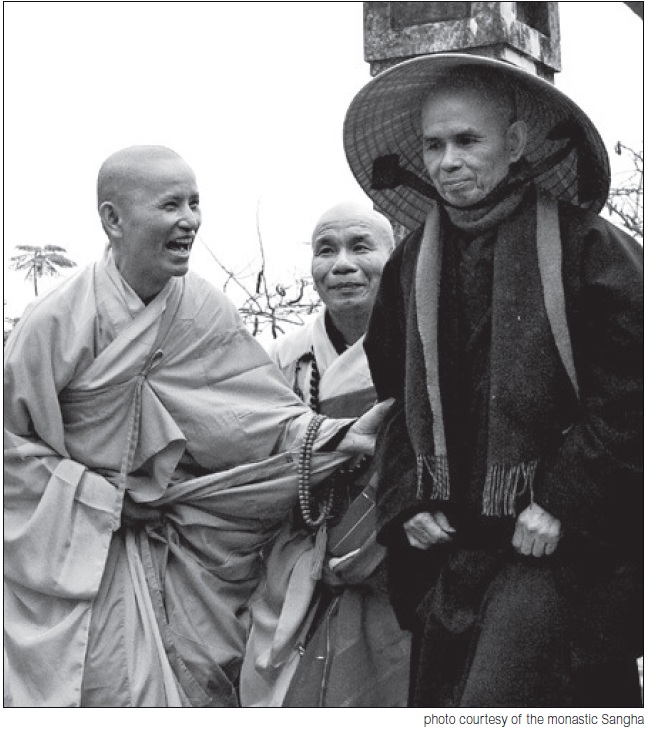

During the war, Thich Nhat Hanh was moved to find an appropriate and beneficial way to bring the teachings and practices of the Buddha directly to the real suffering of the people. In 1966, the Tiep Hien Order, or Order of Interbeing, was founded when Thay ordained three women and three men (including Sister Chan Khong, at that time a layperson) as the Order’s first members. Thay invited these first ordinees to become the foundation of his vision of a fourfold Sangha of monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen committed to studying and practicing the Bodhisattva path by living the Fourteen Precepts or Mindfulness Trainings. Today there are over 1,000 Order members worldwide and thousands more who have been inspired by the Tiep Hien Order and its Mindfulness Trainings.

-- Jeanne Anselmo, True Precious Hand

Dear Sangha, today is the eleventh of June 2010. We are in the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in the Great Compassion Temple. The Institute is also called the No Worry Institute. Today we are going to hear a teaching about the Order of Interbeing.

When we wear the brown jacket, the brown robe of a monk or a nun, we have to manifest that spirit, the virtue of humility. We do not say that we are worth more than someone else, better than someone else, that we have more authority or power than someone else. We have a spiritual strength. That spiritual strength is very silent; it makes no sound. It is the silence of the brown color. When lay people put on the brown jacket, they should put it on in the spirit of humility; the spirit of the power of silence.

The Meanings of Tiep

In English we say the Order of Interbeing, but the words are Tiep Hien in Vietnamese. The word Tiep has many meanings. The first meaning is to accept, to receive. What do we receive, and from whom do we receive it? We receive from our spiritual ancestors the beautiful and good things, understanding, insight, and virtue. We receive the wonderful Dharma, the seed of insight. The first thing an Order member needs to do is to receive what the ancestors have transmitted.

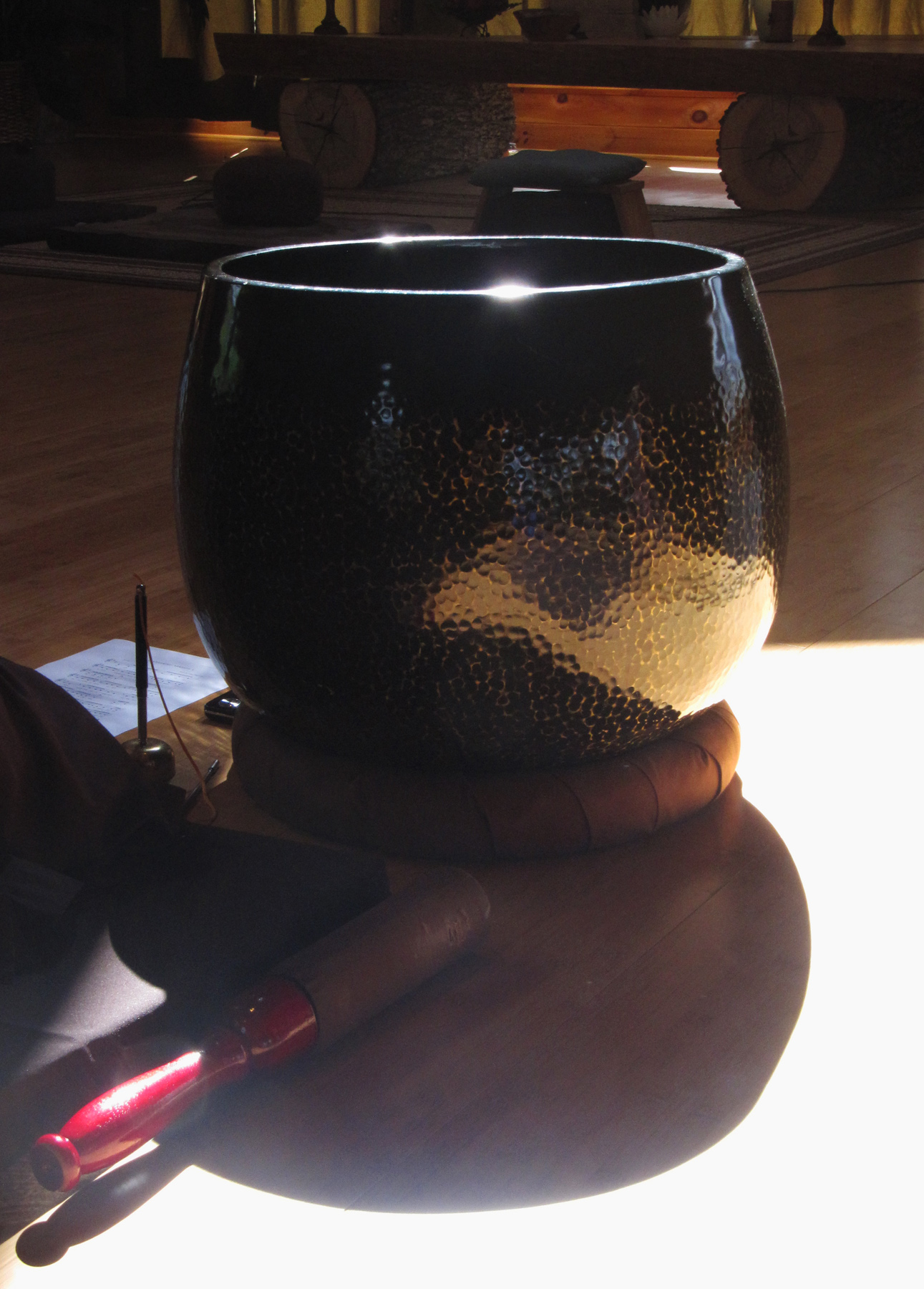

Sometimes our ancestors transmit, but we do not have the capacity to receive the transmission. For example, we can learn from the way Thay invites the bell. Thay invites the bell in such a way that the sound flies up into the sky. But sometimes even after two or three years some of us still cannot invite the bell properly. It’s still very sharp and astringent, or muted and obstructed.

If you practice watching Thay or an elder brother or sister, you will know how to invite the bell. When you are close to Thay and your elder brothers and sisters, you can learn a great deal from them. You can receive very quickly from them.

The way that Thay stands and walks is also a transmission. You just need to observe, and you can receive from the Buddha, from the ancestors, from those who have gone before. And sometimes we receive from those who are younger than us. What we receive is our heritage. This heritage is not land; it’s not money; it’s not jewelry. It is the heritage of the true Dharma. We have to ask ourselves: How much have I received? The ancestors really want to transmit, to give to us. But because we don’t have the capacity to receive, we let down the person who gives. We are not kind to the person who gives when we don’t receive the gift. So learning is a matter of receiving. We have to be there to receive, to learn. When we have received we can continue the ancestral line. Therefore the first meaning of Tiep is to receive.

Once we have received, we use it. We nourish it. Then we can be part of the continuation of the Buddha, of the ancestral teachers, of Thay. A child who is loyal to his parents or grandparents can receive direction from them. A student who has loyalty to his teacher is one who continues his teacher. We have to receive the aspiration and the practice of the Buddha, of the ancestral teachers, and our own teacher of this lifetime.

The third meaning of Tiep is to be in touch with. What do we have to be in touch with? We have to be in touch with the present moment, the wonderful life that is present in us and around us. The birds sing. The wind soughs in the leaves of the pine. If we’re not in touch, our life is wasted. When we are in touch we are nourished, we are transformed. We grow, we mature. Being in touch also means being in touch with the suffering in our own body and our own person, the suffering in our environment, in our family, and in our society. Then we will know what we need to do and what we should not do in order to transform this suffering.

On the one hand, we need to be in touch with what is wonderful, because that will nourish us. And on the other hand, we have to be in touch with our suffering so that we can understand, love, and transform.

The first meaning is receive. The second is continue. The third is to be in touch with, to be in contact. That is what is meant by the word Tiep.

The Meaning of Hien

Hien is the second word. It means the thing that is present. What is present? Life, paradise, our own person. Tiep Hien is to be in touch with what is happening now, here, what we can perceive now, in the present moment.

What are you seeing now? The Sangha, the pine trees, the drops of rain. Be in touch with them. And also we have to be in touch with the suffering in our lives. We cannot stay in our ivory tower with our dreams and our intellectual thoughts. We have to be in touch with the truth, the wonder of the truth. This is the Dharma door of Plum Village, living peacefully, happily in the present moment.

The word Hien also means to realize, to put into practice, to make something a reality, make something concrete. This allows us to have real freedom. We do not want to live a life of bondage, a life of slavery. We want to be free. Only when we are free can we be really happy. Therefore we want to break the nets or the prisons which keep us from being free. These prisons are our passion, our infatuation, our hatred, our jealousy. Just like the deer who gets out of the trap and is able to run freely, the monk or nun who practices is like a deer who is not caught in a trap, who is able to avoid all the traps and jump or run in any direction.

There is a very short sutra, just two sentences, that describes monastics as like the deer who overcome all the traps and are free to go where they like. As a monk or a nun, as a layperson, we are all disciples of the Buddha. We do not want to live a life of bondage. We want to be free. So we need to practice. Our daily practice liberates us. We are not caught in fame. We are not caught in profit. We are not looking for a position in society, for some authority or power. What we are looking for is liberation and freedom. That is realization. So Hien means to realize, to manifest.

Another meaning for the word Hien is to make appropriate. To update, to make suitable for our society here and now. So it is also important for us to be aware and responsible for offering the Dharma in a skillful way, appropriate for our society and our time.

Engaged Buddhism

With all these meanings of the two words, Tiep Hien, how can we possibly translate it into English as one or two words? We learn all the meanings from the Vietnamese (which have their root in Chinese), and then in English we just say Order of Interbeing. From this deeper understanding we know the direction of practice of the Order of Interbeing. We know that it means Engaged Buddhism, Buddhism that enters the world.

Engaged Buddhism means going into life. The monastery is not cut off from life. A monastery has to be seen as a nursery garden where we can put our seedlings. When those seedlings have grown strong enough, we have to bring them out and plant them in society. Buddhism is there because of life. Life is not there because of Buddhism. If there was no life, no world, there wouldn’t be Buddhism.

We have Buddhism because the world needs Buddhism. Therefore our practice center can be seen as a nursery garden in which there are the right causes and conditions for us to raise to maturity the small seedlings. Once they have been made strong enough, they are brought out and planted in the world, in society. So our training and our practice in the monastery are preparation to go into the world.

In Vietnam people started to talk about bringing Buddhism into the world as early as 1930. When Thay was growing up he was influenced by this kind of Buddhism. He knew that in the past Buddhism had played a very important part in bringing peace and making the country strong. He learned that Buddhism prospered in the Le Dynasty and the Tran Dynasty, and that the kings practiced Buddhism. Buddhism was the spiritual life, the spiritual force, the Dharma body of a whole people. The first Tran king, Tran Thai Tong, had a deep aspiration to practice by the time he was twenty. He was able to overcome great suffering with the practice of beginning anew. He wrote books about Buddhism which are still available today. His book called “The Six Times of Beginning Anew” proves that, although he was a king ruling the country, he was able to practice every day, offering incense, touching the earth, practicing sitting meditation six times, each time for twenty minutes. I don’t know if President Obama can do the same. As a ruler or a politician we should not say, “Oh, I’m too busy. I don’t have time for sitting meditation, for walking meditation.” If a king can do it, we cannot make the excuse that we have too much work, that we don’t have time to practice.

Applied Buddhism

Engaged Buddhism has been in our tradition for hundreds of years. We are not a new movement; we are only a continuation. When we understand what is meant by Tiep Hien, our process is very easy. And Engaged Buddhism leads to the next step, which is called applied Buddhism.

The word applied is used in a secular context. We use it like it is used in “applied science” or “applied mathematics.” For example, when we talk about the Three Jewels—the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha—we have to show people how they can apply the teaching of the Three Jewels. How can we practice taking refuge in the Three Jewels? Just reciting “I take refuge in the Buddha, Buddham, Saranam, Gacchami” is not taking refuge. That is just announcing that you are taking refuge. In order to take refuge, you have to produce the energy of concentration, mindfulness, and insight. Then you are protected by the energy of the Three Jewels. When we practice “I come back to the island of myself, to take refuge in myself,” we have to practice breathing in such a way that we produce the energy of mindfulness, concentration, and insight. When we practice like that, we produce the energy of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and then we really are protected by the Three Jewels. As members of the Order of Interbeing, our practice must be solid, so that whenever we have difficulties, we know what to do to get back our equanimity, our balance, our freedom, our solidity. One of the methods is taking refuge in the Three Jewels.

At universities in the West, you can now get degrees and doctorates in Buddhism. This kind of Buddhist study is not applied Buddhism. You can be fluent in Pali, Sanskrit, and Tibetan, and in all the different teachings of the two canons, but if you get into difficulties and don’t know what to do, your Buddhism doesn’t help you.

We need a Buddhism that will help us when we need it. When we teach the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, the Five Powers, the Five Faculties, and the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, all these teachings have to be applied in our daily life. They should not be theory. We can teach the Lotus Sutra very well, but we have to ask ourselves: how can we apply the Lotus Sutra to resolve our difficulties, our despair, our suffering? That is what we mean by applied Buddhism. If you are a Dharma teacher, as a monk or a nun or a lay person, your life has to be an example of the teachings. You only teach what you yourself practice.

When we lead a Dharma discussion, when we give a Dharma talk, it is not to show off our knowledge about Buddhism. We just teach those things which we are really practicing. If we teach walking meditation, we have to practice it successfully, at least to some extent. If not, then we should not yet teach it. There are people who don’t need to give Dharma talks, but are very good Dharma teachers, because when they walk, stand, sit, and lie down, they are in touch with the Sangha. They’re always in harmony, peaceful, joyful, open. That is a living Dharma talk. These people are precious jewels in the Sangha. These people are not just monks and nuns. There are also lay people practicing very well, very silently, and the monks and nuns respect them very much.

Because our destiny is to bring applied Buddhism to every situation, we really need Dharma teachers. Therefore, the Order of Interbeing is an arm that stretches out very far into the world. The number of Order of Interbeing monks and nuns is not enough. We need Order of Interbeing laypeople also. The lay Order members are the long hand of the fourfold Sangha that stretches out to society. We need thousands of lay Order members to bring the teachings into the world.

With our brown jacket which represents our humility, which represents the power of our silence, we have to build a Sangha where there is no competing for authority or for power. Where there is brotherhood and sisterhood. Where we look at each other with loving kindness.

This is something we can do. If we are in harmony with each other, if we have brotherhood and sisterhood, we can do it. The fragrance of our Sangha will go far, and Thay will be perfumed by that fragrance. That is our work.

I hope that in the future we will be able to organize long retreats for Order members so they can strengthen their practice, strengthen their aspiration, strengthen their happiness, and fulfill the obligation which the Buddha has transmitted to them. We have to receive it and we have to realize it. That is what is meant by Tiep Hien, to make it a reality.

If our Sangha in the West is not yet a place where people can love each other, then we are not yet successful. Who takes responsibility to make the Sangha a beautiful Sangha with brotherhood and sisterhood, worthy to be given the name of Sangha? That is us, only us, as members of the Order of Interbeing. In our local Sangha, we can do that. We should not say, “Because that person is like that I can’t do it.” We have to say, “Because of me; my practice is not very good. Because I don’t have enough humility, because I don’t have enough of the strength, the power of silence, that is why we can’t do it.” Our destiny is to continue to receive, to be in touch to the best of our ability, and to realize the transmission of the Buddha.

Each member of the Order needs to have a fire in her heart which pushes us forward and makes us happy. Whether we are sweeping the floor for the Sangha, cooking for the Sangha, watering the garden for the Sangha, cleaning the toilet for the Sangha, we’re happy because we have the energy, we have the aim. The aim is not fame, profit, or position. The aim is the great love, wanting to be a worthy continuation of the Buddha, of our teacher and our ancestral teachers.